In the beginning, there was unlimited promise. A startup born out of an innovative mind and nurtured with federal grants was setting up shop in, of all places, Little Elm—a tiny speck of a suburb on the shores of Lake Lewisville. Some two decades later and for a variety of reasons, however, the company’s once-bright promise remains largely unfulfilled.

Back in 1996, things were different. The idea of a projected 600 jobs coming to Retractable Technologies’ new 22,500-square-foot plant was huge for local officials, who pitched in $300,000 for roads and other improvements. “This is the project of the century for Little Elm,” the town mayor proclaimed at the startup’s announcement.

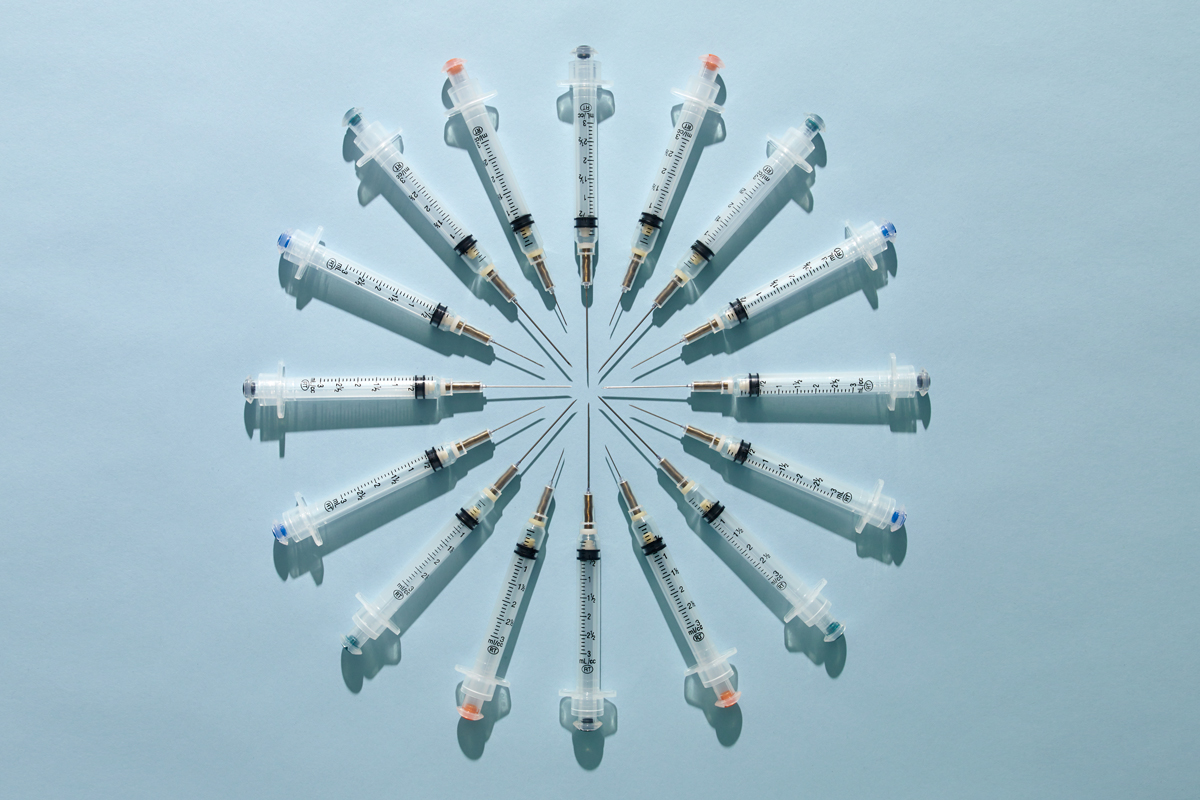

And Thomas J. Shaw, a mechanical and structural engineer, expected his revolutionary product to make waves beyond Little Elm as well. With the help of $650,000 in grants from the National Institutes of Health, Shaw had developed a medical syringe with an automatic retraction feature. After the plunger is fully depressed, the needle pops back into the syringe’s cavity, where it can’t stick the nurse or technician. The design offered a solution to the roughly 600,000 accidental needle sticks that occurred each year at hospitals—accidental sticks that put medical workers at risk of contracting HIV, hepatitis, and other serious diseases.

Shaw secured patents on his design, began gathering investment cash from North Texas doctors and others who saw promise in the business, and formed Retractable Technologies Inc., a public company trading under the symbol RVP on the New York Stock Exchange.

Soon after launching production, however, Shaw realized he was being shut out of selling to hospitals by an alliance of major medical supply manufacturers and powerful purchasing consortiums that buy supplies in bulk for about 80 percent of the nation’s health systems.

Shaw’s upstart company—which encouraged publicity with press releases decrying the power of the giant group purchasing organizations—was soon gathering national media attention that painted Retractable as the victim of a market rigged against innovative entrants. And, there was ample evidence that the portrait was valid, though many accounts left out the caveat that the purchasing systems had been established to help hospitals cut their expenses and tamp down healthcare costs.

Despite having the most foolproof “safety needle” on the market, Shaw told reporters, his company was rejected by most of the more than 2,000 hospitals his salespeople had visited because, among other things, they were bound by agreements to buy from incumbent companies. “There’s an AIDS and hepatitis C epidemic, and we can’t even show our retractable safety needles in most hospitals,” he told the Houston Chronicle. “Free competition as it stands in healthcare is dead.”

Shaw’s complaint eventually took the form of a federal lawsuit naming as defendants several of the purchasing organizations, as well as several rival medical supply manufacturers, including industry heavyweight Becton Dickinson and Co., of Franklin Lakes, N.J. The 119-year-old company, often referred to as BD, currently has about $10 billion in annual revenue and as much as 80 percent of the total needle and syringe market. On the eve of trial in 2004, and in a series of earlier settlements, the defendants paid out a total of $100 million to Shaw’s company to drop its federal suit.

The award, which was cut nearly in half by legal fees and costs, still was several times Retractable’s net annual sales that year of $21 million. Last year, a dozen years after the big settlement, Retractable would have shown an operating loss had it not collected yet another jury award: a $7 million judgment from BD for patent infringement arising from BD’s attempt to market its own retractable syringe. As of this writing, Retractable is awaiting an appellate court decision in still another antitrust case it brought against BD in 2007—that one involving its rival’s contracting and advertising.

Retractable may have winning ways in court—and in media stories portraying it as a noble David in a world of anti-competitive Goliaths—but, more than 20 years on, it still can’t find much traction or sales growth in the marketplace. In fact, its net sales have been flat or down for the last five years. According to a BD court filing, Retractable’s share of the “safety” market, a subset of the total needle and syringe maket, stood in 2010 at just 6 percent, compared to 49 percent for BD. And, after outsourcing much of its production to China, Retractable’s workforce now numbers 136, down from the 175 it employed 15 years ago.

Company executives say Retractable continues to be the victim of its rivals’ anti-competitive schemes. But, some observers say Retractable has ridden that horse a bit too long. Some of the company’s growth problems, they contend, have been self-made, or an honest consequence of normal competition. Just because you believe your product is aces—as Sony did in the 1980s with its Betamax videotape system—doesn’t mean that you automatically get to win.

‘A Different League’

Shaw, who is president, chairman, and CEO of the company and owns about half its stock, declined to be interviewed for this story, saying through a company lawyer that he could not discuss Retractable while it’s involved in pending litigation. But the feisty 65-year-old has given so many interviews over the years, the story of the company and its founding is well documented.

Shaw grew up in Mexico and Arizona, where his father worked as a chemist. As he related in a 2010 Washington Monthly story, a chalkboard hung over the family dinner table where math and science problems were puzzled out. Shaw went on to study engineering at the University of Arizona and eventually launched his own small engineering firm in Lewisville. He began tinkering with the idea of a safer syringe in the late ’80s, after being moved by a news story about a California doctor who was infected with HIV after being accidentally pricked with a used, contaminated needle. It took four years and more than 150 design changes for Shaw to arrive at a working prototype.

Retractable Technologies accused its bigger rival of using bundling, rebating, loyalty discounts, and other sales incentives to “keep hospital doors shut to Retractable.”

Since he started producing and marketing his syringe, Shaw has insisted that not only is he marketing a product, he is saving lives. Along with California-based healthcare system Kaiser Permanente and the Service Employees International Union, Shaw was a major proponent of a groundbreaking law passed in California requiring hospitals to transition to safer needles. The federal government followed suit in 2000, and President Bill Clinton recognized Shaw’s role in the measure’s passage by inviting him to the signing ceremony and giving him a pen used to sign the bill into law.

Shaw, who by 2002 was several years into the lawsuit he’d filed against rival BD and the hospital buying groups, hoped that year to convince the federal government to ban nearly all syringes from the market—save for the one he produced under exclusive patents.

In an urgent-sounding letter to the FDA in September 2002, Shaw wrote, “We suggest that both ‘conventional’ (non-safety) syringes and ineffective so-called ‘safety’ syringes be removed from the market and outlawed by the FDA. A sincere concern for the health, welfare—and very lives—of this nation’s dedicated frontline healthcare workers demands no less.” He went on to criticize the effectiveness of his competitors’ safety designs—which include sliding-sleeve syringes, shielding needles, and pivoting needles—and asserted that it is “well-documented, scientific fact” that Retractable’s products “are in a different league from many so-called ‘safety’ needle devices.”

Some of the proof, he insisted at the time, was being “suppressed” by Kaiser Permanente hospitals in California, which had done a study showing problems with BD’s shield-design safety syringe. He wrote that BD and another large competitor were “ramping up the production of their so-called ‘safety’ products” and relying on faulty studies. The situation, he wrote, “should wave Enron flags” around BD and another company he had sued in his 1998 antitrust complaint.

The FDA, however, declined to take Shaw’s suggestion that it hand him most, if not all, of the $3 billion-a-year syringe and injection-needle market.

An Early Disaster

That Shaw would ascribe sinister motives to Kaiser Permanente, his one-time ally in the push for safer syringes, would seem strange, were it not for the fact that, by the early 2000s, Retractable Technologies and the California-based hospital group had a bit of unpleasant history together.

In its earliest days, when Retractable was shut out from the hospital market, it relied on contracts with government agencies such as the Veteran Affairs Administration, prisons, Indian reservations, and organizations too small to be part of the giant group purchasing systems. But in 1999, Kaiser Permanente signed a landmark, one-year contract to buy Retractable’s syringes. Before the year was up, however, Kaiser was complaining about the Little Elm company’s reliability as a supplier as well as the quality of its product. As a Kaiser spokesman explained later, Kaiser ordered 2,239 boxes of syringes but received only 343. There were also instances of product failure, Kaiser reported, including one in which the needle detached from the syringe and remained in the thigh of a 7-month-old baby.

“That is erroneous,” Michele Larios, Retractable’s vice president and general counsel, said in a recent interview. She said the contract was cancelled instead as the result of a $30 million grant for a safety-needle study that BD gave Kaiser just a month after Retractable got in the Kaiser door. “They interfered,” she said. “We delivered the orders that were placed in a timely fashion.”

In filings in the lawsuit to which Larios referred, Retractable complained that Kaiser ordered the company’s products “in sizes and quantities which did not reflect actual usage,” and that “reported minor defects” were “within standard tolerances.”

Whichever version of these stories is true, the Kaiser chapter was an early disaster for an upstart company seeking to gain momentum with a top-shelf customer.

Highest-priced Safety Syringe

Since those days, Retractable has enjoyed some successes. It gained access to several group purchasing organizations and, through its most recent lawsuit, was able to force BD to correct several wrongful claims it made about Retractable’s products that Retractable says hurt its ability to compete. In notices to the industry published in February 2015, BD admitted that its comparative advertising had misstated the amount of medication wasted by its syringes compared to Retractable’s, and that its claim of having the “World’s Sharpest Needle” was also false and misleading.

Still, Larios says, the anti-competitive activity—she calls it “lying to customers” —continues. “Our ability to engage the market has been significantly impacted by the anti-competitive activity that has been engaged in,” she says. She declined to detail how that continues beyond what was alleged in the company’s second lawsuit against BD, which covers a period ending in 2010. When asked what BD might have done specifically to contribute to Retractable’s 15 percent decline in revenues in 2015 compared to the year before, Larios declined to say.

BD contends in its court filings that there are plenty of reasons in the realm of fair market competition to explain why Retractable has had trouble. For example, testimony in the 2013 trial showed Retractable’s syringe was the highest-priced safety syringe among the various types offered. It sells syringes it manufactures for 13 cents for as much as 31 cents. In contrast, prices for BD safety syringes and those of its two biggest rivals fell in a range of 21 to 23 cents. During the period at issue in the case—2004 to 2010—Retractable’s prices were between 41 percent and 71 percent higher than its competitors,’ the filings said.

BD contends in its court filings that there are plenty of reasons in the realm of fair market competition to explain why Retractable has had trouble. For example, testimony in the 2013 trial showed Retractable’s syringe was the highest-priced safety syringe among the various types offered. It sells syringes it manufactures for 13 cents for as much as 31 cents. In contrast, prices for BD safety syringes and those of its two biggest rivals fell in a range of 21 to 23 cents. During the period at issue in the case—2004 to 2010—Retractable’s prices were between 41 percent and 71 percent higher than its competitors,’ the filings said.

Testimony also pointed out that Retractable’s primary product, the “VanishPoint” safety syringe, has less utility for hospitals than some of the competing designs with removable needles. Although more expensive, it can’t be used for tasks such as giving injections with pre-filled syringes, withdrawing fluid from the body, or attaching to a needle-less IV system. A defense witness, Dr. Carl Vartian, an infectious disease expert from Houston, testified that Retractable’s design “has very limited use within hospitals.” Safety syringes using removable needles have greater utility and hence are better sellers, BD maintains.

Retractable addressed just that issue when, earlier this year, it announced that it is adding a new removable-needle syringe to its product line. The so-called EasyPoint will allow clinicians to change needles and perform such functions as using pre-filled syringes and collecting blood, the company said in a release.

Jack Duncan, a writer/editor at Retractable who fields media inquiries, said in an interview that the company has been able to be listed with some purchasing organizations that buy for hospitals. “But just because they list you in the catalog doesn’t mean they’re going to do much business with you,” he said. BD’s contracts with potential customers are still a big barrier for the company, he added.

Indeed, BD’s contracts were a major issue in Retractable’s 2007 antitrust lawsuit against the industry giant that went to a jury in Marshall, Texas, in 2013. The case is currently before the U.S. Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals in New Orleans. “BD’s exclusive contracts with hospitals make competition based on price and quality impossible,” Retractable asserted in its filings. It accused its bigger rival of using bundling, rebating, loyalty discounts, and other sales incentives to “keep hospital doors shut to Retractable.”

But the judge in the Marshall case instructed the jury that volume and market-share discounts, like other low prices, are not anticompetitive under the law merely because smaller sellers cannot match them without losing money. And the jury found BD’s contracts were not anticompetitive, rejecting Retractable’s claims that BD’s contracts restrained trade, decreased competition, or injured the Texas company.

Still, other parts of the mixed verdict amounted to a big win for Retractable. Jurors found that BD made false claims about Retractable’s products—the needle sharpness and wasted-medication advertising—and attempted to monopolize the market through “deception.” They awarded Retractable $113 million in damages, an amount that was automatically trebled under antitrust law. There was also an automatic award of attorneys’ fees, which amounted to $12 million. So, should it prevail in the appeal, Retractable stands to collect a total of $340 million from BD—an award equal to nearly 15 times its current annual sales.

Myriad legal issues surround the case, which drew the interest of a group of legal scholars who filed a friend-of-the-court brief. They were concerned that the “heavy artillery” of antitrust law, with its trebling of damages, was being used in what was essentially a false advertising case.

In its appeal filings, BD doesn’t dispute that its advertising was false. But it’s seeking to overturn the verdict because, it says, false product advertising is not an antitrust violation, and there was no evidence it did anything to exclude Retractable from the market. During the period when it allegedly was trying to gain a monopoly, BD’s market share declined nearly 10 percent, the company points out.

Larios, Retractable’s general counsel, says the case is about more than just false advertising, and that jurors heard a variety of evidence that BD had attempted to monopolize the safety syringe market, including its violation of Retractable’s patents.

In their appeal filings, Retractable’s lawyers pointed out that testimony showed BD planned to sell low-cost retractable syringes and dominate as much as 70 percent of that market as soon as Retractable’s patents began expiring in 2015. As early as 2007, a BD project team had concluded that while Retractable was “weak” financially, its intellectual property position was “strong” until 2015, when the 20-year patents protecting its chief product would expire.

It was compelling evidence of BD’s drive to dominate the market. During the period covered by the lawsuit, it was noted that Retractable had nearly 70 percent of the retractable syringe market—a position protected by its patented technology.

But, that lawsuit aside, how does the patent issue bear on Retractable Technology’s future? In its 2015 annual report, published this spring, Retractable said that although some patents on its VanishPoint syringe were expiring in 2015 and 2016, another patent “will continue to provide patent coverage for VanishPoint syringes until 2020.”

So, with its chief product facing patent expiration in less than four years, another existential challenge lies on the horizon for the plucky little company from Little Elm. There’s little doubt that when it happens, bigger and more established players will be ready to pounce. Again.