On August 12 of this year, Bill Ackman, a silver-haired hedge fund billionaire, sat in front of remote-controlled cameras in the black-backdropped studio where PBS’ Charlie Rose show is filmed and quietly began defending himself.

Ackman, a 47-year-old New Yorker, had acquired a $900 million stake in Plano-based J.C. Penney Co. Inc. in 2010 and gained a seat on the company’s board. Then he aggressively pushed the iconic, 111-year-old department-store chain, founded in 1902 by the son of a Baptist preacher, to radically reinvent itself. Ackman urged his fellow board members to oust longtime CEO Mike Ullman and to replace him with Ron Johnson, the savant behind both Apple’s Genius Bar and the computer company’s sleek retail stores.

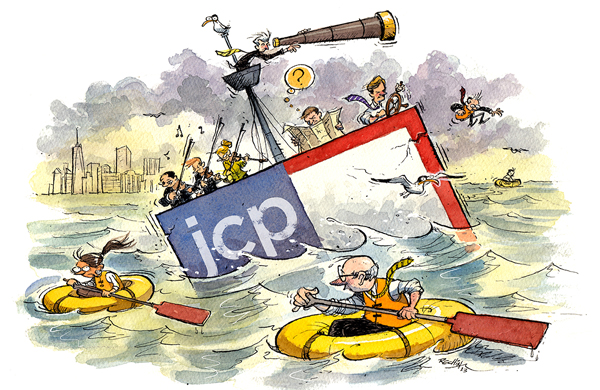

But Johnson’s tenure at the top of J.C. Penney was anything but tidy. Sixteen months later, the company’s stock had cascaded nearly 50 percent, 19,000 employees had lost their jobs, and sales had fallen by more than 25 percent—an almost unheard of slide for a major retailer. The board, Ackman included, fired Johnson in April and rehired Ullman. Then, by August, Ackman was publicly calling for Ullman to be fired again. “In my opinion,” Ackman wrote in a letter to the board that he released to the media, “Mike is overly optimistic about the near-term future of J.C. Penney.” Ackman also accused his fellow board members of dragging their feet on finding a replacement for Ullman, who he insisted was only supposed to be an interim CEO upon his return.

Calling out fellow corporate board members in that way—in public—is almost as unheard of as J.C. Penney’s financial free fall. And among those who had criticized Ackman for it was Howard Schultz, the billionaire CEO and founder of Starbucks. (Ullman, not at all coincidentally, has long served on Starbucks’ board.)

“Here’s the situation,” Schultz said live on CNBC the day after Ackman released his letter. “This is the truth. This is not fiction. Bill Ackman was the primary engineer and architect of recruiting Ron Johnson to the company. He and Ron Johnson co-authored a strategy that has fractured the company and ruined the lives of thousands of J.C. Penney employees. … Bill Ackman has the blood on his hands for being the architect and the recruiter of Ron Johnson and then the co-author of the strategy.”

Three days later, on the same day he quit the company’s board, Ackman, who has taken an activist position with companies as diverse as Wendy’s International, Target Corp., and Herbalife, sat at Charlie Rose’s round table. Speaking in a flat, calm voice, he told Rose, “Frankly, I’m not the only guy on the board who believed in Ron Johnson. The board was very supportive of bringing in Ron Johnson as CEO of the company.

“I don’t control J.C. Penney,” he added. “I am one member of a board of 11 directors.”

He may have said that dispassionately, but Ackman made a powerful point. J.C. Penney’s board, which includes some of the biggest names in North Texas business—Thomas Engibous, formerly board chairman of Texas Instruments; Leonard Roberts, previously chairman and CEO of RadioShack; and Colleen Barrett, president emeritus of Southwest Airlines—bought into and voted in favor of the very same vision Ackman promoted. And, those same board members then failed to stop the execution of that vision—even though Johnson botched it right from the start. “This board has been fiddling while J.C. Penney burns,” says an executive at the company’s headquarters who survived Johnson’s 15 percent reduction in the corporate staff.

People familiar with the board’s thinking now say that several board members regret not firing Johnson sooner or, at least, realigning his strategy when it went oh-so-wrong, oh-so-fast. So why didn’t they? You can’t ask them, because the board members aren’t talking publicly. But we can, at least, look at what went wrong with J.C. Penney’s corporate governance; at who shares blame for the problems; and at who the optimist investors are that have begun betting—again—on J.C. Penney’s next comeback.

THE VACUUM & THE STEAMROLLER

We need to begin with history and then go to math. These are important subjects as far as J.C. Penney’s present is concerned. And the lessons will be quick. So, let’s begin in 1987.

That year, W.R. Howell, then CEO of J.C. Penney, went to the company’s board and told them of his vision to relocate the company from Midtown Manhattan, the fashion center of the country, to an undeveloped lot on the prairie in Plano, Texas. The plot was part of the Legacy Business Park, a mostly conceptual space owned and solely occupied by Ross Perot Sr.’s Electronic Data Systems. There, Howell envisioned that J.C. Penney could build its own headquarters and take itself into a new era. He staked his career on it, actually, telling the board that if the move didn’t work the way he believed it would, “You can fire me. At least then the whole world will know why I got fired.”

Howell told me that story in 1995, when I profiled him for D Magazine in an article titled “Reluctant SAVIOR.” He would not be the last person to be tasked with saving the giant retailer. Ironically, Ullman—whom I profiled for D CEO in 2010—was one of the few CEOs in recent company history who was not tasked with a rescue mission. At least not the first time around.

Now, the math. During J.C. Penney’s last full year in New York, its sales were $15.3 billion, according to Fortune. By 1994, even though half of his top executives refused to make the move to Plano, Howell had led J.C. Penney to $18.9 billion in sales. Six years later, under new CEO Allen Questrom, the company rang up $18.8 billion in sales. In 2006, with Mike Ullman in the CEO’s seat, J.C. Penney registered one of its best sales years ever, with $19.9 billion. Last year, after the company was put in the hands of Ron Johnson, a man who brought high-end designer wares to Target and who made Apple’s retail stores into an unexpected phenomenon, J.C. Penney’s sales were just under $13 billion. For 2013, that number is expected to fall even further.

If all except the last of those numbers sound similar to you, it’s because, well, they are. But there is a key difference. J.C. Penney’s 1989 sales, as noted, were $15.3 billion. Adjust that number for inflation and you get $29 billion in today’s money. You know who made almost $29 billion last year? Macy’s, which had long been J.C. Penney’s leading competitor. And, you know who made $19.5 billion last year, an amount just under what J.C. Penney made in its best-ever year of 2006? Kohl’s, the Milwaukee-based retailer that, until a few years ago, was barely considered a competitor to J.C. Penney.

So, what’s the point of this lesson? Before Ron Johnson was hired in 2011, J.C. Penney had been effectively stagnant for more than two decades. In inflation-adjusted terms, the company had actually lost billions of dollars worth of ground—ground that its competitors have now claimed. We could also do that math in terms of market share, but you get the point already.

And so, too, did activist investor Bill Ackman. His Pershing Square Capital invested $900 million into J.C. Penney stock in 2010 with the belief that the retailer could do much, much better if it only tried something vastly different than what J.C. Penney’s leaders had tried before.

By February 2011, Ackman, along with Vornado Realty Trust’s Steven Roth, had jointly acquired a third of J.C. Penney’s stock, and both received invitations to join the company’s board. In September, Roth announced that he, like Ackman, was selling all his shares in J.C. Penney and quitting the board. As of this writing, that left a mostly long-tenured group on J.C. Penney’s board of directors. Seven of the company’s 10 directors have been on the board six years or longer. Some have been there much longer. The longest tenured: Southern Methodist University President R. Gerald Turner, who has served since 1995. Next longest is Kent Foster, former CEO of Ingram Micro Inc. He’s served since 1998. The other five longest-serving directors have an average of eight years of board service. Many analysts say all that tenure, amid all those same-sounding financial results, signaled a power vacuum at the top of the company—a vacuum that Ackman stepped into and exploited.

“Strategy and planning get tweaked all the time,” says Jack Smith, president of Milwaukee-based Sanford Rose Associates, an executive search firm. “But it is very rare to have a reengineering on the scale J.C. Penney undertook when the company has been so steady. And it is even more rare to find that this kind of reengineering was being pushed primarily by one person. It suggests that there was a vacuum of leadership on the board. If they had a clear idea and direction of where to take the company, how could one person steamroll them into going along with something so radical?”

That’s the identical point Ackman made quietly on Charlie Rose: he was not alone in bringing Johnson in. And there is something to that. Mike Ullman himself wanted Johnson to be part of J.C. Penney. In 2008, before Ackman had invested in J.C. Penney, Ullman, of his own accord, went to California to try and recruit Johnson away from Apple. Whether Ullman was looking to hand-pick a successor or just looking for someone to bring fresh perspective on the stagnant retailer is unclear. (Ullman declined an interview request for this story, as did Ackman.) Either way, well before Ackman was involved in J.C. Penney, the company wanted Johnson for his reputed retailing genius. “What happened,” Ackman said on Charlie Rose, “is we took a brilliant guy with a lot of creative ideas and a lot of terrific experience … and he tried to make a lot of dramatic changes to the company. Probably too fast, too quick.”

MANAGEMENT MISADVENTURES AND THE FIDDLERS ON THE BOARD

If you want to find out just what Ron Johnson did too fast and too quick, or, for that matter, if you’d like to know about any of the 10 CEOs in J.C. Penney’s history, the guy you call is Ed Fox. He’s an associate professor of marketing at SMU. He also holds this title: “The W.R. & Judy Howell Director of the J.C. Penney Center for Retail Excellence.” So what does Fox think went wrong under Johnson? Perhaps surprisingly, he thinks Johnson—and, by extension, Ackman and the rest of the board—got the vision thing right. “I was personally not of the opinion that the vision had been discredited,” Fox says. “I just think their implementation strategy was flawed. So I don’t think his vision ever got a fair hearing. And I’m quite certain that now it never will.”

That’s for sure. J.C. Penney has backed off on nearly every new idea Johnson had—from redesigning stores with “town squares” in the center (places where you might get a free ice cream cone or a free haircut) and wide aisles leading to as many as 100 different brand-name boutiques within, to selling $3,000 Jonathan Adler couches in the new home stores, to … well, actually, let’s go back to those $3,000 couches.

J.C. Penney’s core customer is, and long has been, a woman aged 35-55 who has between $35,000 and $100,000 in annual household income. So how could company executives believe a $3,000 couch would sell? Not everyone did. “If you said, ‘Our customer, she can’t afford this or that,’ you’d probably get fired,” says one headquarters employee. “So you didn’t say anything.” Ackman said something to Charlie Rose, though, about pricing. He said Johnson’s major mistake was taking away J.C. Penney’s sales, discounts, and coupons, in favor of “fair and square” pricing that emphasized everyday low prices and just a few major sales each year. That was one of the first things Johnson did. He rolled out “fair and square” in February 2012, just three months after taking the CEO’s job, and well before he started making physical changes to the company’s stores. It was an immediate flop with customers. “Interestingly,” Ackman said, “people seem to be happier buying something at 50 percent off that costs $50 as opposed to it being marked at $40 and there being no discount.”

Interestingly, there’s more to it than that. Something that maybe an Apple millionaire or a hedge-fund billionaire wouldn’t understand. Buyers don’t just want to buy something at $50 that’s marked “half off” because they’re stupid. They want to buy something at half off because they don’t trust that a company’s everyday low price is, in fact, “fair and square.” This is the American way of haggling. We doubt the price tag, but we don’t confront the seller. We simply remain silent about our misgivings until a sale comes around. And, at J.C. Penney, a sale always came around. In 2011, just 0.2 percent of all products sold at a J.C. Penney store were sold at full price. That means Johnson’s “fair and square” was a radical change in strategy. And, yet, it was never tested with customers before being rolled out nationwide, and it was not vetted in advance by the board.

“I don’t think pressure was coming from the board,” Fox says. “The board gave Johnson time. Even in the face of pretty staggering losses, they gave him time.”

Still, no one expects board members, who are often busy running their own companies, to drill down into the minutiae of a CEO’s strategy. But ever since the economic meltdown of 2008, corporate boards have been increasingly tasked—both by regulatory bodies and by investor advocates—with paying close attention to big issues. Top personnel. Risk. That kind of thing.

There was one big thing J.C. Penney’s board did question Johnson about, according both to published reports and people I spoke with who are familiar with the matter: The rollout of the new-store concept, with its wide aisles, mini-boutiques, and free haircuts. Johnson announced plans for his town-square-centered stores in January of 2012, and began reconfiguring some stores soon after. But by summer, and with sales down by double-digits, board members began questioning whether Johnson should slow his rollout, and maybe even do some consumer testing. Johnson did start updating the board on his progress more frequently after that, and even brought back clearance racks and more sales. But he did not slow his plans to physically remake the stores, nor did he test the plans with potential customers. “I think not testing was a mistake,” Colleen Barrett, the Southwest Airlines president emeritus and a J.C. Penney board member since 2004, told The Wall Street Journal earlier this year.

One source who has spoken with several board members says they believed that not firing Johnson—who was let go in April of this year—as early as the summer of 2012, when the new-store concept was being implemented, was also a mistake.

Johnson had no such hesitations about firing people. In April of 2012, he slashed 15 percent of the company’s headquarters staff in Plano and cut thousands of managers and workers across the country. All told, Johnson’s team cut a reported 19,000 positions, including at least 600 at the corporate headquarters.

Those workers who remained are still stung by comments made by members of Johnson’s team. In a February 2013, front-page Wall Street Journal article, Johnson’s team declared the headquarters to be “overstaffed and underproductive.” As proof, they claimed that employees in Plano had watched 5 million YouTube videos in a single month and that a third of the time headquarters employees spent on the internet was for purposes unrelated to work.

Most of the current J.C. Penney employees I called for this story were enraged by the implication that headquarters staff was unproductive. And some now wonder why neither Ullman nor the board of directors has called for rehiring the workers who were let go. Still, none would go on the record to say so.

J.C. Penney’s employees might feel a little better knowing they aren’t the only ones whose reputations have been maligned by the Ron Johnson tenure. Nor are they the only ones whose fortunes have suffered. Two days after he appeared on Charlie Rose, Ackman announced that he was selling his stake in J.C. Penney. When the sale cleared in late August, he had lost more than $400 million of the $900 million investment he’d made in 2010.

Johnson lost out, too. He earned $1.5 million a year at J.C. Penney, and the company initially gave him $52.7 million in J.C. Penney stock to compensate for the 250,000 stock options in Apple—worth maybe $100 million—he had to leave behind there. Johnson then bought roughly that same amount of J.C. Penney stock for himself, in the form of warrants that he can cash in only if the stock gets back to nearly $30 a share. That’s about twice its current value.

So, let’s give credit where it’s due: The company’s board got Johnson’s compensation package right by making it contingent on the company’s performance. But it didn’t do so well with other executives. The company ponied up $137 million to the executives who were hired by Johnson and either quit or were fired during or after his tenure. It also okayed nearly $20 million in severance to Mike Ullman when he left the company. (And then, of course, it hired Ullman back.) Still, the board has done at least one other thing right of late: It’s looked for more experienced retailers to join its ranks. When Ackman resigned from the Penney’s board on August 14, the board agreed to bring on a retail executive—Ronald Tysoe, formerly of Federated Department stores—and one other board member to be named later. Tysoe is only the second person with significant retail experience to have served on the board in recent years.

That, alone, is cause to question how much the board appreciated the risks involved with Johnson’s overhaul, says Dennis McCuistion, host of a Dallas PBS show called The McCuistion Program and executive director of the Institute for Excellence in Corporate Governance at the University of Texas at Dallas. “Was there significant industry expertise on this board—people who would know something about what the retail business is?” McCuistion asks. “That’s a question one would have a hard time answering in the affirmative. You need some people on a board who have ‘been there and done that,’ and I think that may have been where J.C. Penney’s board lost their way.”

He may be right. And there may be a price to pay for the board, as one employee put it, “fiddling while J.C. Penney burns.”

“The board shakeup is not over,” Fox says. “They really backed Johnson all the way. So the problem, while certainly of his making, needs to be shared by the board who backed him the way they did.”

The next window for a major shakeup will be in May, when the company holds its annual meeting and investors can vote to re-elect board members. Or not to re-elect them. Last year, Glass Lewis & Co., an independent governance analysis and proxy voting firm, recommended that investors vote against three current directors: Geraldine Laybourne, former CEO of Oxygen Media; SMU’s Gerald Turner; and Colleen Barrett, the Southwest Airlines president emeritus. And this year David Eaton, Glass Lewis’ vice president of research, said, “Shareholders should question the choices the board has made.”

Maybe shareholders should do more than just question the choices. Maybe they should vote to hold the board—and not just Bill Ackman and Ron Johnson—accountable for J.C. Penney’s disastrous run.