The luxury Swiss watchmaker Hublot specializes in timepieces like the Big Bang model, which can be encrusted with diamonds and cost a whopping $5 million. So, with bling like that in its showcases, you know Hublot took an ultra-judicious approach recently when it weighed the relative merits of NorthPark Center and Highland Park Village as the site of its first boutique in Dallas. The company decided eventually in favor of NorthPark, an enclosed super-regional mall at Northwest Highway and North Central Expressway, over Highland Park Village, a smaller, open-air luxury lifestyle center less than 4 miles away in Highland Park.

“We looked at both centers and thought, why not have a store in each one?” says Hublot executive Rick De La Croix. “But in the end we decided we had to choose one, based on the location and the terms and the conditions. … Our clientele is global, so we have to be in a 360-degree environment, and that starts always with the management. Highland Park Village is a very beautiful mall, but it wasn’t as strong in the competition as NorthPark was.”

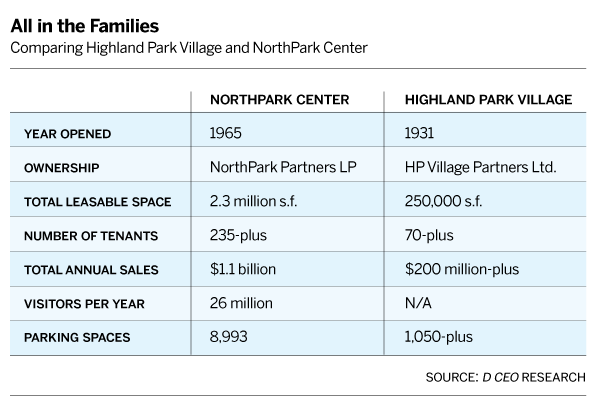

Hublot’s choice between NorthPark and Highland Park Village is one that’s been faced by a number of upscale retailers in Dallas, where these two iconic, family-owned shopping centers compete not only to attract high-end tenants but affluent patrons as well. And, there are plenty of those patrons to attract. According to one research firm, the neighborhoods in the vicinity of both centers are extraordinarily wealthy, with an estimated 15,000 residents with annual incomes over $250,000 and more than 2,000 homes valued at $1 million or more.

“There’s so much money around,” says Herb Weitzman, chairman and CEO of The Weitzman Group, a Dallas real estate company. “Everybody’s paid off their debt. Their house mortgages have been paid. There’s just a lot of income out there.”

North Texas logs about $80 billion in retail sales annually—and, in heavily retailed Dallas, the joke is that shopping is a competitive sport. But one expert says the overlapping trade areas of NorthPark and Highland Park Village constitute an especially sweet spot for the retail trade. Both shopping centers are “best of class,” says Chuck Dannis, president of valuation firm Crosson Dannis Inc. and an adjunct real estate professor at SMU’s Cox School of Business. “A super-regional mall like NorthPark has at least a 50-mile primary trade area, meaning that while they compete with Highland Park Village, they also draw from the entire DFW area. Highland Park Village, on the other hand, appeals mainly to the high-end shopper, and sits right in the heart of the watermelon as well.

“Just like the Mavericks and Cowboys compete for the same fans, having them so close together is like having the Cowboys in the Super Bowl and the Mavs winning the NBA Championship every year,” Dannis says. “We consumers really benefit.”

Observers say NorthPark is one of the top five enclosed malls in the country, while Highland Park Village—which locals call “the Village”—is one of the country’s top five specialty centers. Tipton Housewright, a principal at Omniplan, a Dallas architectural firm that’s worked on both shopping complexes, agrees. “Everyone around the country knows about those two projects,” he says. “They’re very well-respected. The fact that they’re both family-owned is significant.”

While family-owned retail centers were common in the 1950s and ’60s, most have given way over time to ownership by corporations such as public real estate investment trusts, says Malachy Kavanagh, a senior vice president at the International Council of Shopping Centers. Today, he adds, corporations own “probably 98 percent” of all the nation’s big enclosed malls. However, retail centers like NorthPark and the Village “can be highly successful, because of their family ownership. They know their properties inside out, and nothing gets past them,” Kavanagh says. “The key is that they’re situated in very good locations, with a very good customer base.”

These days, the Dallas families that own the Village and NorthPark are battling for that local customer base with a variety of new plans and strategies. Both also are rolling out new ways to lure more international shoppers. And, each is grappling with its own unique problems as well.

NORTHPARK: A TASTEFUL PARTNERSHIP

Nancy A. Nasher and her husband, David J. Haemisegger, are sitting in a conference room at NorthPark’s corporate offices. With Nancy positioned at the head of the table, they’re talking about the shopping center that Nancy’s father—developer and art patron Ray Nasher, with help from his wife Patsy—put up on the edge of what was then a North Dallas cotton field.

NorthPark, called the world’s largest climate-controlled retail establishment when it opened in 1965, has come to be known in large part for the art and landscaping features that are important parts of its sleek, modernistic design. Among them: a manicured, 1.4-acre open-air greenspace in the mall’s heart called CenterPark, and artworks by the likes of Andy Warhol, Henry Moore, Frank Stella, and Mark di Suvero. Following a 2005-2006 expansion costing $250 million, the multi-level center now boasts at least 235 stores and restaurants in about 2.3 million square feet of leasable space. The mall has long been the No. 1 tourist destination in Dallas-Fort Worth and, in 2007, was named one of the “7 Retail Wonders of the Modern World” by industry publication Shopping Centers Today.

Today the couple owns, manages, operates, and leases the shopping center after buying out their equity partner, mall developer Macerich Co., and taking out bank loans worth $500 million, in 2012. (Macerich received $119 million in the buyout, $44 million more than the investment it made in NorthPark eight years earlier.) David tends to the mall’s financial side—managing relationships with banks, pension funds, and life companies, for example. Nancy says she’s in charge of “all the marketing, all the events, all the advertising, the landscaping, the tenant leasing, where the tenants go—everything you see.”

No doubt, the collection of tenants the pair has assembled is impressive. With Nordstrom, Dillard’s, Neiman Marcus—the top-performing Neiman’s in the country, no less—and Macy’s as anchors, the center has more than 70 stores or restaurants that are exclusive to the Dallas-Fort Worth market. Among them: Bottega Veneta, David Yurman, Kate Spade New York, Eiseman Jewels, MontBlanc, Salvatore Ferragamo, Valentino, and Versace.

The powerhouse lineup has enabled NorthPark to more than double its sales over the last decade, to an estimated $1.1 billion in 2012, or $900 per square foot. Only a handful of U.S. shopping centers enjoy higher revenue. While the couple declines to disclose the mall’s average leasing rate—“it varies,” Nancy says simply—they say they’re constantly aiming to generate more volume by fine-tuning the tenant mix.

“Our goal is to ‘harvest the garden,’ to make sure we have the very best retailers that are out in the U.S. or even abroad, and that we bring them to NorthPark so you can find the very best in every category here,” Nancy says. “Even in the last 10 years, new tenants that we’ve had we’ve either reduced or expanded in size, because they’ve evolved. Two new tenants, for example—Versace and Michael Kors—were of various sizes, but they found that one needed more space, and one needed less. So it’s a constant refinement of our mix and also bringing in new ideas, new retail concepts, which we will always do.”

Is there a trick to doing this well? “It’s something one learns how to do over time,” Nancy answers. “My parents did it together; we’ve always done it together. It’s years and years of experience, developing our taste, knowing what concepts are new and cutting-edge.”

Adds David: “This is a big property, and it’s important that we have tenants from Louis Vuitton to the Gap. The Gap shopper may shop at your high-end jewelry store, too. One thing we’ve found is that people really like the variety of stores here. They want quality, regardless of price point.”

Despite the center’s success over the years, there have been some stumbles. One involved Barneys New York, a high-end department store that came in as a tenant twice at NorthPark—and failed both times. Observers say the second failure, announced in 2012, was especially embarrassing for the mall, because other luxury retailers had been located near Barneys to complement its offerings. In May, NorthPark announced that two home-furnishings stores, Arhaus Furniture and Fixtures Living, would occupy most of Barneys’ 88,000 square feet of space beginning next summer. Two existing NorthPark retailers—CH Carolina Herrera and Kate Spade—will take most of the rest.

David says that Barneys’ first exit was due to a bankruptcy proceeding, and that the second came after the store failed to develop and pursue a sound business strategy. “We give our tenants great locations and say, ‘We’ll support you through marketing and events, but you have to come and manage your business.’ Retailing is a tough game, and you always have to be up on your game,” David says. “I don’t think Barneys had the vision. They had the desire, but they didn’t have a strategy they could implement. … You have to sell the goods, and they didn’t. We can’t do that for them.”

The couple also rejects the idea that stores like Valentino and Oscar de la Renta took their locations in the mall because of Barneys. “The Valentino’s of the world know there’s a customer base here, and when they know there’s enough of one, they’ll look to do a store,” says David. “That’s the way that happens, more than any one store leading the way.”

In addition, the couple has had to contend with bad publicity about “increased crime” at NorthPark. Media reports of criminal activity there—including aggravated assault, robberies, and vehicle thefts—seemed more frequent after the 2005-06 expansion, which added 1.2 million square feet of space, including a food court and a 15-screen movie complex. In response the mall hired more security officers and imposed a curfew on certain teenagers aged 17 or under.

“As the center has become bigger, a lot more people are coming to the center and, quite honestly, we have a DART rail line near the center, making it more accessible,” David says. “When that happens, certain things can occur. We’ve addressed it, though, with a lot of off-duty Dallas police officers who walk the property. It’s the highest line item in our budget. We take it seriously. We spend what we need to provide a secure environment. Statistics are actually down … but we are victims of our own success, maybe, because we were so successful and so many people came.”

Looking to the future, the couple say they’re focused on attracting more global shoppers to NorthPark, placing advertisements in publications that target tourists from China, Mexico, and Canada, for example. “Dallas has become such an international market,” David says. The couple recently added a new luxury concierge service for local and out-of-town visitors, offering personal shopping and executive transportation. And, down the road, they may consider putting in more retail space in the surface-parking lot between Nordstrom’s and Park Lane.

Do the owners consider Highland Park Village to be an important competitor? I wondered. “There are tenants that make sense for NorthPark, and tenants that make sense for Highland Park Village,” David replies carefully. “Louis Vuitton has a store at NorthPark, not at Highland Park Village, and they do amazingly well.

“I think [the Village is] trying to maintain a high-quality approach to what they’re doing, and that’s what we try to do, too,” he goes on. “They have the way they do it. We have the ways we do it. At the end of the day, it’s good for Dallas.”

THE VILLAGE: AMBITIOUS IMPROVEMENTS

If Highland Park Village is smaller than NorthPark, at 250,000 square feet of leasable space, the ambitious growth strategy of its owners seems outsized, even audacious. “We’re trying to make Highland Park Village an international brand name,” says Ray Washburne, one of the center’s four owners. “We want to be the Rodeo Drive … in this market.”

The Village may have enough cachet to do it. The swank shopping center at the southwest corner of Preston Road and Mockingbird Lane has more than 70 tenants, including some of the finest names in luxury retailing, like Dior and Chanel Boutique. The property itself is more than 80 years old, built by the developers of Highland Park as a “town square,” with handsome colonial architecture reminiscent of Spain, Mexico, and California. Billed as the nation’s first self-contained, open-air shopping center when it opened in 1931, the Village was declared a National Historic Landmark in 2000.

Some 35 years before that, however, the center had begun falling into disrepair under a disengaged owner. Then in 1976 it was acquired by the Henry S. Miller Co., for $5 million. Henry S. Miller Jr., a Dallas real estate legend, and his partners jump-started the flagging property, replacing local tenants with national retailers like Ralph Lauren. Herb Weitzman of The Weitzman Group, who helped lease the Ralph Lauren store, says its arrival was key. “Ralph Lauren did so much business at that store, substantially higher rents became possible at the Village,” he says. “That’s when it changed from being strictly mom ‘n’ pop.”

The shopping center got its latest ownership group in 2009. That’s when the descendants of Miller sold the Village for $171 million to Washburne, his wife Heather Hill Washburne, Heather’s sister Elisa Summers, and Elisa’s husband, Stephen Summers. Heather and Elisa are the daughters and heirs to the oil fortune of Al Hill Jr., whose mother, Margaret Hunt Hill, was a daughter of the famed Texas oil billionaire H.L. Hunt. (The partners say “trust structures” were involved in the acquisition and in the current ownership arrangement.) Washburne is a real estate entrepreneur who helped start the Mi Cocina restaurant chain. His brother-in-law once worked for the real estate company founded by Roger Staubach. Both say they grew up near and shopped at the Village as youngsters. The two married couples make decisions about the center “by consensus,” with Stephen handling the center’s leasing and Ray serving as the operation’s president.

The new owners had aggressive plans for the Village from the get-go. Once they took over, for example, they vowed to hike the center’s average annual retail rents substantially, from $36 to $120 per square foot or more. Today, Washburne says, the average asking rent on new leases is $165. That’s still “a bargain,” he says, when compared to rents on Rodeo Drive in Beverly Hills or Madison Avenue in New York.

Today, the brothers-in-law say, Village fashion stores occupying fewer than 5,000 square feet are doing about $1,850 in sales per square foot. By comparison, Florida’s Bal Harbour Shops—billed as the world’s “top-producing” shopping center—recently did more than $2,500 per square foot in sales, according to the International Council of Shopping Centers. Total annual revenue at the Village, Washburne says, has doubled since 2009 to “north of $200 million.”

The center’s owners have secured such results partly by spending “many millions” to renovate the property—new landscaping, a new clock tower, resurfacing the parking lot, remodeling the theater—but, more important, by rejiggering the tenant mix. Although they continue to be “very conscious” of local tenants such as Deno’s shoe repair shop and a Tom Thumb supermarket, the owners say a concerted effort has been made to maximize sales for higher-end stores like Hermes, Harry Winston, and Alexander McQueen. Out went the 8,200-square-foot Banana Republic, for example. In its place came Christian Louboutin, Diane von Furstenburg, and Saint Laurent Paris. St. John was downsized from 4,200 square feet to 2,400, and the remaining footage was leased to Akris. “St. John’s sales were up 12 percent in the smaller space,” says Stephen Summers. “… We’ve got 250,000 square feet here. So we’re trying to fit in as many [stores] as we can. We have so much demand that if somebody gave me 100,000 more square feet, I could lease it in a heartbeat.”

Like NorthPark Center, the Village has faced its share of challenges. Some observers have decried the loss of longtime mom ‘n’ pop stores like Cooter’s camera shop—Washburne says Cooter’s simply became obsolete—and fear that treasured local tenants like Deno’s and Café Pacific eventually will get the boot. (Washburne says there’s “nothing on the table” along those lines.) Others lament a lack of convenient parking at the center. Washburne counters that more than 1,050 spaces are available for shoppers and that, in any event, valet parking is offered free. Still another complaint involves the recent displacement of the Crystal Charity Ball nonprofit group, which for nearly four decades had occupied office space at the Village. When it lost its month-to-month lease there, the ultra-influential charity moved to nearby Turtle Creek Village. In late May an adjacent Highland Park Village office occupied by another high-profile nonprofit, Cattle Baron’s Ball, said it would leave as well.

Crystal Charity’s exodus, it’s clear, left a bad taste in the mouth of some Village retailers. “The Crystal Charity ladies would patronize Escada, Chanel, Hermes, Carolina Herrera here,” one Village store manager says. “Cattle Baron’s picks up the rest: Tory Burch, Trina Turk, Jimmy Choo. Plus, they are just lovely women to have here. If you want a group of qualified, high-caliber influencers at your shopping center, I just don’t understand the decision to move Crystal Charity out of the Village. You’d think [the owners] would ask themselves: Do you need to make more money by adding another vendor—or build on the loyalty and keep the neighborhood feel as you become an international destination?”

Washburne, for his part, says the owners had no choice but to ask Crystal Charity to leave. “We’ve supported them in this space for a long time, but we had to move them in order to do asbestos removal, update the electrical wiring, deal with [Americans with Disabilities Act] issues,” he says. “This space was the last one to get that. We have to fix it up to modern specs, and they needed space immediately. We love both those charities and have been very supportive, but … we’re a retail center, not an office center.”

So, what other changes can be expected at the Village? Like its bigger rival on Northwest Highway, the open-air center is starting up concierge and personal shopper programs and advertising in international publications. It’s spent “hundreds of thousands of dollars” this year on a slick marketing catalog, hiring fashion writers for it, shooting photographs in New York, mailing out 75,000 copies to consumers in the Southwest and Mexico, all in an effort to burnish the Village brand. “Dallas is becoming a gateway city like Miami, Chicago, and San Francisco,” Washburne says, explaining the outreach. “The city is changing very rapidly.”

The Village also is toying with the idea of adding a hospitality property to its mix. According to an online publication called Hotel Law Blog, putting hotels in shopping centers has become a hot trend. “The most asked-for thing here is a hotel,” Washburne says. “At some point we’re working on trying to do a boutique hotel. It might have 70 to 100 rooms.” Where would it be located? “I can’t say,” he replies. “I don’t want to upset the tenants in those spaces.”

So, do the owners of the Village consider NorthPark Center to be their chief competition? “We view NorthPark almost as complementary,” Summers replies. “We tend to do well in certain areas; they do well in others. We excel at high-end luxury, street-front retail, where you can pull up and walk right in. We also have an extremely high ‘capture’ rate; there’s very little price-resistance here. If you go into a store, you’re actually going to leave with something. NorthPark has a lot more traffic, but the customer there does less volume per transaction.”

Washburne says the families who own the Village “respect” NorthPark and are impressed by its success. “We’re more local, though,” he adds. “This is the town square. People make multiple trips here to the Starbucks each day. The Village Theatre’s the same way. We’re also more nimble. We can do a 1,000-square-foot pop-up store. That’s sort of a pain for [the mall]. Much like Ray Nasher built NorthPark and it’s still in their family, the Village is a legacy investment for our families. Like the Nashers, we look at future generations.”

ONE OR THE OTHER, PLEASE

Despite all the gracious words from both camps, the quality of the rivalry between these two ambitious, iconic, and successful family-owned retail centers occasionally comes through. That was evident when we told Washburne about Stephen Urquhart, president of Switzerland-based Omega watches, who said he faced a choice like Hublot’s before deciding finally to open Omega’s first Dallas boutique at NorthPark Center in January.

While making that decision, Urquhart said, “it was very important to see the traffic count at NorthPark, as well as the blend of brands there: fashion brands, clothing brands, jewelry brands, not only watches. I just visited Highland Park Village, too. It was very nice, very beautiful. Having seen both, I think NorthPark was best for us. But, Dallas is a big market. Maybe someday we could develop another boutique here, perhaps at Highland Park Village.”

Hearing this, Washburne scoffed. “If they’re at NorthPark,” he said, “we’re not going to put it here.”