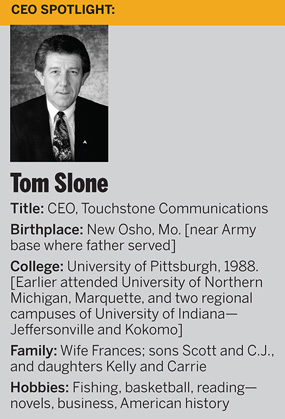

A Business Model That Worked

Aslam and Slone’s newly created Touchstone Communications recruited four Pakistanis who were dispatched to a San Antonio call center for training. The instructors were amazed by their rapid retention of whole new skill sets. “It was the first indication [the business model] would work,” Slone recalls.

And, in the beginning, the model did work. The Pakistani business grew to 800 employees eventually generating revenue of $500,000 a month, Slone says. But roughly 90 percent of the company’s work was for subprime mortgage lenders. In retrospect, Touchstone had put far too many eggs in the home-loan basket. As long as housing was booming, though, why argue with success?

In January 2007, a top client called NovaStar Financial, a subprime lender, offered to pay $1.5 million for a 30 percent stake in the venture, and promised even more call-center work. In anticipation of the new work, Touchstone snapped up $165,000 worth of computers from Aslam’s family business. But then, Kansas City-based NovaStar became an early casualty of the industry’s collapse. Overnight, most of Touchstone’s contracts evaporated, just like the mist shrouding Islamabad’s Margalla Hills. The company downsized rapidly to 200 workers.

It was not a good year for Pakistan in general. Musharraf triggered unrest when he sacked the chief justice for the second time for questioning his regime’s legitimacy. The general-president declared a state of emergency. Still, Slone paid well-publicized calls on the increasingly unpopular military leader.

Slone hoped that a new contract with a non-mortgage lender—specifically, a Norwegian-owned, Pakistani cell-phone provider called Telenor—would save Touchstone. But the deal was sabotaged—by none other than Aslam, who candidly admitted his mischief.

Aslam’s American dream

Aslam declined to comment for this story, but in a 2008 interview for the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, he told me that Telenor’s negotiator was a Touchstone employee who had been fired and was now “spinning” Slone along. “This was a very slick kid with a grudge,” Aslam explained. Moreover, he said, “if Touchstone couldn’t make money [selling calls] at $9 and $10 an hour [per worker] for U.S. companies, how could we make any [money] at $3.10 an hour [placing calls for] a Pakistani company?”

Slone insists the deal was real and could have been profitable at a far lower rate because the call centers were empty during the day and Telenor would pick up line costs.

Like Slone, Aslam had dramatically achieved his own version of the American Dream. The son of cotton gin owners in Pakistan’s Punjab province, Aslam arrived in Texas at the age of 17 to study electrical engineering at the University of Houston. Instead of cracking the books, he says, he got bitten by the real estate bug.

Aslam dropped out his final year to buy up rental houses, whose prices would crash during the 1980s savings and loan crisis. He moved on to strip shopping centers, relocated to Fort Worth, and acquired what was the Color Tile building near Sundance Square. Now called the STS Tower, it was re-engineered to handle high-speed optic fiber lines for high-volume data storage centers.

Aslam was no passive investor. He took matters into his own hands, according to a lawsuit filed later by Slone against Aslam in a Texas state court. Flying to Islamabad, Aslam allegedly used his authority as a director of Touchstone’s Pakistani subsidiary to sell the lease on one of its call center properties for about $163,686, then took possession of the company checkbook and wrote checks to his family’s computer company for $338,830, the suit claims.

“I was forced to act unilaterally,” Aslam told the Star-Telegram in 2008, insisting he had “acted in the best interests of Touchstone.” He contends that the money was used to repay part of a $500,000 debt that had long been owed his family’s computer business by Touchstone. Slone, who had invested $700,000 of his own money in the business, disagrees, contending the debt to Aslam’s family firm had been reduced by then to just $50,000.

Besides his civil case against Aslam in a Texas Court, Slone also struck back in Pakistan by lodging a defamation case against Aslam. At issue is a “disinformation campaign” in the Pakistani media that claimed Slone had embezzled from Touchstone, using the proceeds to buy his Colleyville home and to pay for a chauffeured luxury car. Slone said he bought the house with his Associates deferred compensation and drives his own car, purchased with personal savings.

Aslam, furthermore, maintains that the men sent to occupy the call center were not rustic goat herders from his native village, as Slone claims, but actually the firm’s own security guards. Slone calls this characterization absurd.

Back in Fort Worth, meanwhile, the judge ordered Aslam to surrender $338,000, which was then deposited in a court-controlled bank account. The legal case went to binding arbitration, was settled in Slone’s favor, then was forwarded to a state court for confirmation. The arbitration finding, which eventually may be appealed, returns all the disputed money to Touchstone, plus interest and court fees.

Despite all he’s been through, Slone insists he has no regrets about the foreign call center business—or about his foray into Pakistan. “I’ve met some great people there,” he says.

And any obituary for Touchstone Communications would be premature, he adds. A revived U.S. bank sector has provided some business, such as processing 2,000 potential borrower leads a month, none of them subprime this time, Slone says. One contract has Touchstone scheduling appointments for a home security alarm installer. Another has it verifying insurance applications. Revenue now runs between $150,000 and $160,000 a month, Slone says, and there have been months this year that actually turned a profit. January, he adds, was the company’s best month since 2007.

Even so, Slone is planning an exit strategy from Touchstone. Once he’s cut free from the legal entanglements with Aslam, he says, “I’ll be looking for a way for our [Pakistani] employees to buy the company—like an ESOP.”

Looking back on it all, Slone is asked, what has the Pakistani experience taught him? His simple reply: “Vet your business partners.”