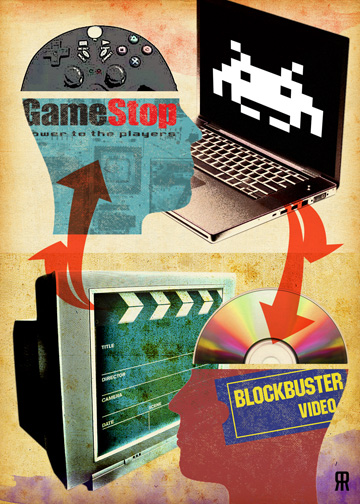

It’s tempting to look at retailers that rent dvd movies and games and ask: Why aren’t you dead yet? If you do ask, you learn that a massive amount of consumer entertainment is moving online—but not all at once.

Analysts say more than 25 million U.S. broadband households regularly watch full-length TV shows online, out of 114.9 million U.S. TV households, as measured by Nielsen. About 20 million households watch movies online, but movie theaters still outdraw all of the nation’s theme parks and major U.S. sports teams combined.

Until all movies and games are delivered and consumed online, providing consumer entertainment will be more complicated than supplying a digital version of anything-you-can-buy-on-DVD.

That’s why it’s worth watching how two Dallas-area entertainment giants who aren’t going all-in on digital content delivery are reaching their customers. Dallas-based Blockbuster and Grapevine-based GameStop are using the Internet and their ability to mine consumer data in ways they’ve never done before, providing opportunities for better service. Both companies, in their own ways, are preparing for an all-online world by honing systems that provide enough individual guidance so that consumers spend less time browsing and more time enjoying the movies or games they bought or borrowed.

Video Killed the Video Store?

Online content delivery didn’t kill Blockbuster’s business, but smart online services tied to a wide variety of devices could help it win back customers.

Blockbuster’s competition is well-documented. Through the first half of 2009, NPD Group says 45 percent of the videos rented by consumers were borrowed from video stores. But 19 percent came from kiosks like Redbox, and 36 percent came from Netflix and other subscription services. Blockbuster can’t afford to ignore changing consumer tastes.

CEO Jim Keyes is intently focused on providing entertainment convenience with no strings attached. “Is the iPod worth a darn without iTunes?” he asked in an October 2008 interview in D CEO.

That’s a great question: What services will drive tomorrow’s home-entertainment devices? This year Blockbuster is trying to provide an answer.

Last September, the movie-rental giant promised it would close as many as 960 stores nationwide by the end of 2010. Even as it sheds big stores and expensive leases, the video store isn’t going away. “It is, for us, about getting into the living room in a really effective way as a complement to the stores, not as a replacement for them,” says Kevin Lewis, Blockbuster’s senior vice president of digital entertainment.

Blockbuster’s activities outside the store are numerous. Its movie-rental kiosks are turning up in drugstores and grocery stores across the country. The company is also baking its online movie rental and purchasing service into some 10 million devices by the end of this year, including TiVo DVRs; Samsung LCD TVs, Blu-ray players, and home theater components; Xbox 360 game consoles; and even a $99 dedicated set-top device for movie rental and storage from 2Wire Inc.

The company also says it will make movies available for rental and purchase via select Motorola mobile phones.

Blockbuster’s well-reviewed iPhone application takes the drudgery out of roaming and staring at aisles of DVD jackets. The app allows customers to locate the nearest physical copy of the movie they want and to get a glimpse of what movies happen to be the most-often rented in their neighborhood store.

Another new service creates a stronger tie to Blockbuster’s remaining stores. Direct Access is a program where Blockbuster will mail you any movie in its inventory that’s not readily available for rent in its stores. You can return the rented title via mail or bring it back to the store, and subscription isn’t required for the service.

None of the above would be worth mentioning were it not for a huge step forward the company has made with its customer relationship management software—those databases that keep and sort the likes of customer data, movie rental histories, and account information. “We have just finished uniting, for the first time, all of our backend systems—our store system, our mail system, and our online system—so now you have one single Blockbuster account and all of that transaction data is unified,” Lewis says.

“Because we’ve spent the time uniting that data, we’re now poised to offer very specific, personalized consumer services, recommendations, and offers that we wouldn’t have been able to do in the past.”

The elephant has learned to dance.

Not Playing Games

For GameStop, retail stores are still a growth business, not a balance-sheet problem. The games giant is the 39th largest company in Texas and number 296 on the Fortune 500, making it bigger than other DFW-based retail giants such as Neiman Marcus, RadioShack, and, yes, Blockbuster. In 2009, GameStop was on track to open some 400 new stores worldwide and says it sees a better than 45 percent return on investment during each store’s first year.

Wal-Mart sells console games, too. But GameStop says its small store footprint, well-trained staff, and constantly changing selection of new and barely-used games give it an edge. “Can you imagine a world where all the games in the world are relegated to the bottom shelf of a locked-up case in Wal-Mart?” says GameStop CEO Dan DeMatteo.

The digital delivery of console games hasn’t eroded GameStop’s business. In fact, the chain claims that the number of people digitally downloading games is only about one percent of the 500 million visitors it gets in its retail stores worldwide. And, unlike movies and music, which can be streamed, console games can only be enjoyed when their code is stored and running on specialized hardware, like an Xbox.

“I don’t know that I see digital downloading of console games as a big issue because of broadband speeds and file sizes,” says DeMatteo. Also, he notes that the business of selling games differs greatly from the movie biz. “There’s no margin expansion for the publishers in a downloaded game,” he says. “Our studies have concluded that consumers pay less for digital than they do for boxed products.”

And with boxed products, you have something in hand to trade in for store credit towards future purchases.

While game publishers and broadband penetration are keeping digital delivery of full console games at bay for now, GameStop is exploring other ways to make money online. It acquired Ireland’s Jolt Online Gaming, a maker of browser-based games, and with that purchase is learning how and where it can get into the business of PC games, which appeal to more casual gamers.

GameStop is also looking at ways to sell add-on gaming content—downloadable weapons, etc., that enhance game play—to its members who are both loyal store visitors and frequently buy digital content online. J. Paul Raines, the company’s chief operating officer, says that about 70 percent of the people who are downloading PC games and game content are also regular GameStop shoppers. “There’s a huge opportunity to migrate folks to add-on content,” he says.

Those add-ons are small-dollar transactions, but they get consumers in the habit of buying digital goods from GameStop. That might give the retailer an edge when console games eventually become an online commodity.

“We’re not ignoring the digital world,” DeMatteo says. “We’re going after the piece that’s realistic today, which is add-on content, and we do believe people are spending their time gaming in different fashions today, which is browser-based gaming, and we bought a company to learn.”

Another acquisition teaching GameStop some new tricks is Micromania, a 26-year-old French gaming retailer. One of Micromania’s tactics GameStop will soon employ is allowing members of GameStop’s Edge Card membership club to go online and see the current trade-in value of all the games they’ve purchased through the years. By seeing the untapped value in their games, consumers might be quick to do more frequent trade-ins.

GameStop has a kiosk strategy, too, but it’s a bit different than renting movies on the cheap outside of pharmacies. Coming to its stores soon will be interactive kiosks where consumers can see screen shots, interactive videos, and other exclusive content surrounding new and upcoming game titles.

“Our game is the assisted sale, the value-added sale. That’s where we play,” says Raines.

Digital expediency, to be sure, is an important part of the overall consumer entertainment market. But it’s not a zero-sum game. Also vital are services that provide convenience without forcing consumers to change their habits. Not everyone is ready to adorn their entertainment cabinets with 15 different types of set-top boxes or to watch Lawrence of Arabia on an iPhone.

Phil Harvey is the editor-in-chief of Light Reading, a TechWeb publication that covers the telecom industry. He lives in Fort Worth and doesn’t know what to do with his Apple TV.