Given the current climate, the time seemed right to speak with several top execs who might serve as role models for CEOs uneasy with their present circumstances. Luckily, we found three who fit the bill. Each has gone through various transitions in his career; each was at the pinnacle of success yet, for various reasons, decided to make a change. All three offer instructive examples and advice.

Making a difference

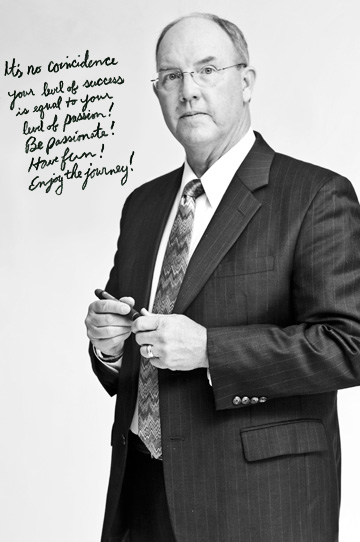

At first blush, 59-year-old Richard Wright’s career seems like a series of U-turns.

He went to college at Louisiana Tech and nursing school at Northwestern State with the intention of becoming a nurse anesthetist, but never took his state boards after graduation. He found a job as a pharmaceutical sales rep in Houston and became the top salesman in less than a year. But he quit the business four years later, courtesy of almost annual cuts in his commissions and territory.

He returned to his hometown of Shreveport, La., and spent a decade or so in the direct sales business building a profitable network of distributors, only to jump into a telecom IT start-up with two partners in the mid-’80s. While the business venture went well, the partnership gradually went south, and Wright sold his shares to his partners in 2004.

After 30-plus years of dynamic change, Wright was at a loss as to what would come next. “I didn’t know what I was going to do,” he admits. “I was only 54, and you can only play so much golf.”

For Wright, the light came on when he realized that his next move would not be about making money. Rather, he “wanted to do something to make a difference in people’s lives.” He had always enjoyed politics, and the local congressman, U.S. Rep. Jim McCrery, was an old friend from their Louisiana Tech days. Learning that McCrery planned to retire in two to four years, Wright felt that fate was steering him in that direction.

He took a job as the congressman’s senior staffer in Louisiana, representing him at speaking engagements, ribbon cuttings, and fundraisers all across the 4th Congressional District. As Wright learned the ropes and made the rounds of rubber-chicken dinners, it became common knowledge in Shreveport that he would make a run for the seat once McCrery vacated it.

But fate had played a trick on Richard Wright. He would never make it to Washington, because another old friend who had lived a few blocks away steered him toward Dallas instead.

Charlie Ragus had founded AdvoCare in Dallas in 1993 and, not long before his untimely death in 2001, had recommended Wright serve on the privately held company’s three-person board of directors. Once a rising star in the direct-marketing industry, AdvoCare, which sells health and nutrition products directly to consumers through independent distributors, stumbled and went through a series of CEOs after its founder’s death. Desperate for new direction, the Ragus family trust, which owns the company, asked Wright to take over as president and CEO.

“No, I’m running for Congress,” he said.

“Pray about it,” they replied.

To his surprise, the more he thought about it, the less appealing that life as a freshman Republican in a House of Representatives controlled by Democrats began to look. Wright decided that he could make more of a difference in people’s lives, specifically in the lives of AdvoCare’s thousands of distributors, by turning that company around.

As a result Wright moved to Dallas and revived a company, rebuilding relationships with AdvoCare’s network of independent distributors and boosting revenues 12 percent, to just under $100 million for 2009, despite the struggling economy. In the process, Wright believes he learned a few lessons that might benefit other CEOs as well.

“Make sure that you’re doing something you enjoy,” he says. “Don’t ‘tread water’ just to get through the day. From my perspective, now is a great time for CEOs to ask themselves, ‘What mark am I going to leave?’ If you’re going to invest yourself, invest in something that will be around down the road.”

His final word of advice? “Make it about more than just making a living.”

Switching industries

After 30 years at the top of the beverage business, Jim Turner in 2005 had visions of a peaceful retirement dancing through his head.

The last time Turner, now 64, had gone through a major change had been 20 years earlier. During the takeover mania of the mid-1980s, he had been president of Dr Pepper when the soft-drink company was purchased by the private equity firm Forstmann Little & Co. As was common practice, the investment firm began to spin off assets to pay down debt, and one of the largest assets was the company’s bottling operations. GE Capital, which was working with the bankers to sell Dr Pepper’s assets, approached Turner with an offer: They would provide the capital to buy the bottling operations in Dallas-Fort Worth, Waco, and Houston if he would come aboard to run the business.

“Buying these plants was hard to turn down,” Turner says. “They were the company’s largest plants at the time, and right in the heartland of Dr Pepper territory.”

Thus the Dr Pepper Bottling Co. of Texas was born, and so was Turner’s career as a business owner. Fast forward 20 years, and the company had grown through expansion and acquisition to annual revenues of $2 billion, which made it the largest independent soft-drink bottler in the country.

It also made Turner a very wealthy man. When Cadbury and the Carlyle Group purchased Dr Pepper in 2000, Turner took the opportunity to sell a big chunk of his business back to the corporation, but part of the deal required him to commit to stay on board as CEO.

“I inherited some problems with the merge,” Turner explains, “and I was traveling constantly—five or six days a week. I just got tired of the travel and the headaches, so I thought, ‘Why not retire?’ ”

Turner, who serves on the boards of numerous public and private companies and nonprofits, imagined he would have no trouble keeping busy even without a business endeavor to occupy his time, and he was probably right. He never tested the theory, though, because he never really tried it. Almost as soon as he sold the rest of his stake in the bottling business, he bought the Texas and California insurance business of Guaranty Financial Services. Suddenly he was a CEO again—and in a completely different industry.

While Turner had owned a small insurance agency in Dallas for years, Guaranty Insurance is one of the country’s largest privately owned, full-service agencies, with $350 million in volume and offices spread across Texas and California. He initially installed the head of his Dallas agency as CEO of his new, much larger holdings, but that turned out to be a mistake.

“The management system for a small agency just did not work for a large company,” he says.

As a result, Turner describes his first year of owning and operating Guaranty Insurance as one of “a lot of ups and downs.” He was forced to take a more hands-on approach to the business while searching for the right person to take the day-to-day reins from him as CEO. He found that person—Mike Haselden—last November.

For CEOs pondering a switch to another industry, Turner offers a few words of wisdom. “Not everything is transferable from one type of business to another,” he says. “Management skills, selling skills, marketing skills—all of these transfer. But a different customer base requires a different skill set. You have to surround yourself with people who understand the technical aspects and culture of the new industry.”

His final bit of advice for anyone thinking of following a similar path is to “go very slowly when transitioning to a new industry.”

“The first thing is to make sure you have strong people around you,” he says. “And you’ve got to know when to say, ‘This is not for me.’ ”

From Nike to SMU

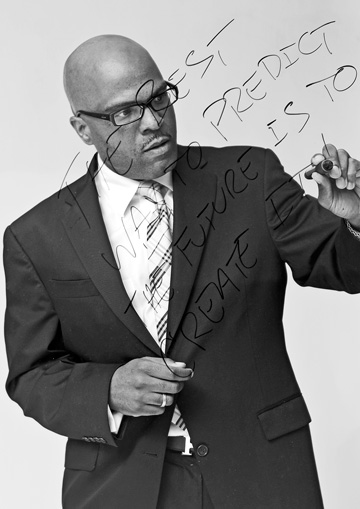

In a previous century, O. Henry might have penned Erin Patton’s tale.

Raised in Pittsburgh by a single mother, Patton easily could have become just another African-American kid dragged down by poverty and crime. Luckily for Patton, however, his mother was a big believer in the power of education and, to this day, he deftly recalls the motto she drilled into his head.

“We are the product of our education, not our environment,” the 40-year-old says with a smile.

The “Erin Patton Story” hinges on a few key turning points. The first came in high school, when he was accepted into the “Inroads” internship program for minority students. Placed with a job at the Pittsburgh Press, Patton parlayed that opportunity into a spot at Northwestern University’s prestigious Medill School of Journalism, where he discovered public relations. He graduated and took a job with Edelman (named the best public relations agency of the decade by Advertising Age), but the restless Patton hadn’t yet found the right marriage between his passions and his day-to-day work.

“At the end of the day,” he says, “it’s about identifying and marrying your passion to what you do. I had agency experience, but I wanted to be closer to the strategic side. I’m also a product of the hip-hop generation, which came of age with a strong sense of brand awareness. We express ourselves through our brand preferences, and I wanted to bring that insight with me into corporate America.”

The door that would allow that to happen eventually opened when Patton picked up the phone and found himself unexpectedly talking to a recruiter for Nike. He soon found himself in Beaverton, Ore., as the company’s U.S. manager for public relations. By 1996 the company’s Air Jordan sneakers had become as much of an icon as their sporting namesake, but the man himself was nearing retirement, and some within Nike felt that once the legend left the stage, people would no longer line up to buy his products.

Nevertheless, Patton sensed an opportunity. During the next two years he wrote a business plan, marshaled the necessary support and resources within the Nike organization, and launched the Jordan brand as a “company within a company,” with himself at the helm. Patton remained at Nike in that role until 2000, when the brand surpassed $350 million in sales and he felt it was firmly positioned for long-term growth. (It has since passed $1 billion in sales.)

“This was a very entrepreneurial opportunity for me,” Patton says, “and also a very important transition. You have to recognize when a window of opportunity exists. I recognized that I had the instincts, the understanding, and the desire to be an entrepreneur. [So] I chose to leave in order to fulfill that passion.”

Patton left Nike to launch the New York-based Mastermind Group as a boutique brand-management agency where he could bring “everything under one roof” to a few select clients. Among Mastermind’s successes was the launch of the Starbury shoe brand for Stephon Marbury and Steve & Barry’s. Mastermind also developed marketing plans for NBA star LeBron James and tennis’s Williams sisters.

While Patton had seen a lot of change in his career to that point—from PR to brand manager to entrepreneur—it was nothing compared to what was to come.

Once Mastermind was on solid footing, he determined that he wanted to earn his MBA. Since his wife Nicole’s family was from the Dallas area, he enrolled in the Cox School of Business at Southern Methodist University, left the New York office in the hands of a managing director, and packed up his young family and moved to Dallas in 2004.

“It is essential to evolve and reinvent myself and the business,” he explains. “Evolution and reinvention are non-negotiable, both for the business and the person.”

True to his word, after earning his executive MBA, he couldn’t help noticing that SMU lacked any sort of sports marketing or sports-management programs, despite the thriving sports industry in North Texas. Patton designed a program, presented it to the dean, and suddenly found himself an adjunct professor in the business school. Although he must now balance teaching a few classes a semester with his continued responsibilities as CEO of The Mastermind Group, his “double life” has benefited all aspects of his career.

“You have to recognize windows of opportunity,” Patton emphasizes. “These allow you to reinvent yourself and yet still maintain continuity in your career.

“Teaching has been great. Academia allows me to stay connected to the youth market,” he says. “Engaging my students with the things that I’m involved in is a win/win. They get real world experience, and I get the benefit of sharp young minds to keep me plugged in.”

Patton, who also teaches undergraduates, has utilized his students in marketing efforts for the NBA Developmental League team in Frisco and a forthcoming product from George Foreman, among other projects. He has used his clout to bring marketing executives from the Cowboys, Rangers, Stars, and Mavericks into his class to speak to students. Such connections resulted in several students interning with the NBA during All-Star Weekend and with the North Texas Super Bowl Host Committee.

“I am setting out to create a different model for what an adjunct professor should be,” Patton says. “I want to turn my class into a lab that marries theory with real-world applicability.”

Obviously, no one’s career path or present situation is identical to another’s. Nonetheless, change is inevitable. The stories of Richard Wright, Jim Turner, and Erin Patton offer valuable lessons on how to manage career change—before change catches us unaware and unprepared.