The story below was published in the October 1979 issue of D Magazine. It is being published online here for the first time. For more context about this piece, please visit this blog post.

Take any current map of Dallas and smooth it flat across a table so that there are no sharp creases to be mistaken for creeks and draws and no humps to suggest relief in an almost reliefless Blackland Prairie. And if you place your index finger in the northwest corner, close to Grapevine and the tracks of the Chicago, Rock Island, and Pacific railroads, you will find the Elm Fork of the Trinity River, a clear blue ribbon on the map, though no one has seen it that color in 100 years, if ever. To the north and south, the Trinity flows more broadly and swiftly, but in Dallas, where it channels through layers of hard Austin chalk, it becomes narrow and cramped. Still flowing, but slowly, half-heartedly. If there’s a reason for Dallas to be where it is, it’s probably the narrowness of the Trinity and the hard, chalky bottom that made crossings easier. Upstream and down, pioneer horses and wagons could sink quickly and forever, but on this stretch, from above California Crossing, where the 49ers set out for glory, all the way down to Hampton and Commerce and Houston and beyond, the footing was more solid and safe.

Now start to run your finger along that blue ribbon toward the southeast, through old Elm Fork Park (now L.B. Houston) with its burr oaks and bois d’arcs and shell mounds where prehistoric peoples shucked their clams and oysters, down to where the Trinity divides, one section flowing into a humorless diversion channel that forms the eastern boundary of the city of Irving, the other toward Bachman Lake Park, now manicured and macadamized beyond reclamation except for a small tract of virgin prairie behind Dunfey’s (née Royal Coach). From here the Elm Fork snakes its way past fashionable country clubs and rows of characterless warehouses on romantic streets like Yellowstone and Sleepy Hollow and disappears temporarily into a broad, green flood plain. If there is such a thing as a primordial landscape in Dallas, it’s here, among the cottonwoods, elms, post oaks, and hackberries that all but obliterate the river unless you’re standing on its banks, or above it, or are following its course with your finger on a map.

And if you continue to run your finger along that ribbon of blue, past the high bluff where John Neely Bryan decided to begin the Dallas adventure, past the shadow of Reunion Tower that mocks the socialist principles of Considerant and his colonizing disciples on the opposite shore, around the perimeter of Rochester Park, named for an access road named decades before by some calculating developer for Eddie “Rochester” Anderson of the Jack Benny Show, eventually you will come to a bend where the Trinity meets White Rock Creek.

It is not a mighty confluence. During the dry season, it is hardly a confluence at all except to the experienced eye. Yet together these two streams drain much of Dallas County, hundreds of square miles. On a map they come together like a leftward-leaning projectile point. And if you place your finger on the tip of that point and start moving northward, up through the fertile bottom lands, past Tenison Park and White Rock Lake, through the tidy trapezoidal channel under Central Expressway, on up to Preston and Keller Springs, all the way to Collin County, where the creek first gurgles from the ground; or better yet, if you were to pack the map, take water and food, and start making your way to the creek on foot, which few Dallasites are inclined to do these days, you would be embarking on a journey through time.

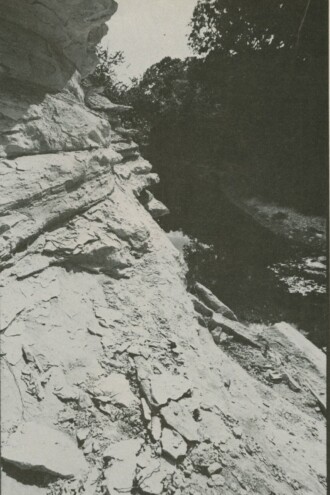

White Rock Creek takes its name from its ubiquitous outcroppings of Austin chalk, which turns a soft tan-white when exposed to the air. These outcroppings were laid down during the Cretaceous period, from 65 million to 135 million years ago, when all of Texas was part of a great inland sea. Compared to, let’s say, Eagleford shale, which is found around Mountain Creek Lake and often yields the remains of pterosaurs, mammoths, and 80-million-year-old carnivorous fish, Austin chalk is fossil poor, good mainly for mussels and clams and a few flecks of fool’s gold. But it is sculptural and dramatic, particularly upstream where centuries of runoff have carved it into deeper and deeper cliffs. Developers love it, and over the years have cut, filled, and channelized the creek in order to back their supermarkets and condominiums up to its scenic banks. From time to time, the creek has risen up to reclaim its territory; but mostly it has submitted. Downstream, closer to the confluence with the Trinity, the chalk is generally covered with many feet of silt and gravel that can support a rich and diverse ecology. James J. Beeman, one of the first settlers of Dallas, writes that in 1842 “the range in the river and creek bottoms was all one’s heart could wish for. The wild rye was thick and plenty, and green as the finest wheat fields could be all winter.” The river was rich in fish, the nearby woods contained abundant pecans and wild plums, as well as deer, coyotes, rabbits, and wild turkeys. Except for high water and occasional Indian raids, there were few reasons for the early settlers to move.

This has historically been the case on the lower reaches of White Rock Creek, roughly the area between Tenison Park and the Trinity River. So long as the food held out and there was no population explosion, prehistoric groups stayed put instead of pushing north where game and vegetation were sparser. The oldest archaeological sites on the creek are here, including several that date from about 8000 B.C., the middle of the Paleo-Indian period. We know very little about the Paleo-Indian groups or most of their successors in the Archaic period (5500 B.C.-500 A.D.) except that they were nomadic hunters and gatherers. It’s believed that the first Paleo-Indian groups crossed into North America via the Bering Strait about 12,000 B.C., then gradually worked their way south, killing hairy mammoths, bison, camels, and other large animals with darts and spears. (Recent discoveries at the nearby Lewisville site, currently under Lake Dallas, suggest that the first migrations might have been much earlier, perhaps around 40,000 B.C.) The best known are the Clovis mammoth hunters, who with their deadly fluted points killed off the last of the great beasts. The groups that followed them—Folsom, Plainview, Scottsbluff—therefore had to learn to adapt to reduced herds and much smaller game. Although there are no intact Paleo-Indian sites in Dallas County, archaeologists have turned up Clovis, Scottsbluff, and Plainview points along the terraces of the lower Trinity, indicating that on their slow southward migration, the major Paleo-Indian groups, including probably Folsom, passed through this area. Most of the points found in Dallas are made of a chert that is foreign to this area, suggesting that in addition to hunting and gathering, these peoples traded extensively.

We know somewhat more about the Archaic sites along the creek, however. In 1925, Dallas archaeologist J.B. Sollberger reported uncovering the remains of an Indian village between the 13th and 16th fairways at Tenison Golf course, east of the creek and within a good tee shot of the flashing neon signs at Keller’s hamburger stand. On the basis of the flakes and points that he found, Sollberger concluded that this site was occupied sometime between 500 B.C. and 500 A.D. He and King Harris, the dean of Dallas archaeologists, also found another small Archaic site a few miles south of Samuell Park. Once again the points found were exotic, probably from somewhere in East Texas, and were undoubtedly acquired in trade. Unlike their Paleo-Indian predecessors, these Archaic peoples could no longer depend on the migrations of large herd animals. They hunted deer and smaller animals, fished the streams, gathered fruits and nuts, and in general led a less nomadic, more settled existence. Some of the other Archaic sites in North Texas have contained gouges, grinding stones, and other agricultural implements, suggesting that by 500 A.D. the climate and ecology were becoming much closer to what we know today.

The passage from the Archaic to the Neo-American period takes approximately 1,000 years of geological time and about an hour’s hike along the banks of White Rock Creek. Beneath and beside the spillway at White Rock Lake are the remains of an Indian village, including four burials, dart and arrow points, seed slabs (metates), bone beads, and a few fragments of pottery. It’s uncertain who these Indians were—possibly Tawakoni or one of the western bands of Caddo—and the cool, matter-of-fact language of the excavation reports completed by King Harris and Forrest Kirkland in 1940 merely hints at what life must have been like around White Rock between 1000-1500 A.D.:

The area below the spillway which is now part of White Rock Lake Park was once an extensive Indian campsite on the east bank of White Rock Creek. … Many artifacts and potsherds similar to those found in East Texas have been found in the midden, as well as numerous fresh water clam shells, deer, and other small animal bones.

All the dirt from Burial A was carefully examined and as much bone as possible recovered. It seemed that the lower portion of the skeleton had been washed out by the flood; only a part of the skull and jaw bone and a few pieces of arm and rib bones were found. …

Burial B was multiple, containing an adult, a child, and a baby. Almost all of the leg bones had been washed out, parts of which were recovered from the bed of the stream. This burial was exposed as carefully as the sticky mud would permit and then photographed and plotted on graph paper. Except for the more solid bones and the two larger skulls, the skeletons were too fragile to be removed. The skull of the adult rested on a pile of burnt rocks and the entire burial lay on a bed of charcoal and ashes. The heads were to the east. (The Record 2, 1941)

To fill in the picture, we might imagine a small, nonmigratory band of Indians subsisting on hunting, fishing, and a limited amount of farming. In the area west of the spillway, where the city is currently extending bike and hiking trails, the Indians probably grew beans, squash, melons, and corn. Excavations along the shore indicate that there were abundant clams and mussels. For meat, the villagers probably hunted deer, rabbit, and fox in the surrounding woods. The area on the southwest side of the creek, from Garland Road east and south to Samuell Park, contains numerous small stopover camps and quarry sites, where hunters came to gather and chip their dart and arrow points. There is no good native flint in Dallas, only a low-grade quartzite that chips crudely; yet it was obviously good enough for most purposes, including killing larger animals like antelope and bison.

And this was emphatically bison country. Beeman writes excitedly that in the 1840s he found the countryside “teeming with buffalo. It was grand to see them, for as far north as we could see, from White Rock across the timber east of Dallas, as well as far as we could see was a solid mass of moving buffalo going north.” At the time of the Indian encampment at White Rock spillway, the herds were probably even larger. On the eastern shore of the lake, on what is known as Dixon Branch, archaeologists have uncovered a large bison kill site dating from around 1500 A.D. It is undoubtedly only one of the many sites that could be uncovered along the small tributaries in this area. Like their ancient forebears, the local Indians drove the bison over cliffs or into dead-end arroyos, then methodically killed and butchered them on the spot. The meat from one kill might last a small band for weeks. Imbedded in the ribcage of the bison found on Dixon Branch were three Fresno-type arrow points made from a kind of chert that is found only in Oklahoma, further indication that even though they were permanent settlers, the Indians in the While Rock Lake area were also trading with distant tribes.

It is difficult for most of us to think about White Rock Lake without a dam—or sailboats or hot rods or panting joggers. Yet all the evidence supports the idea that the lake was a choice site for Indian tribes into the middle of the 19th century, sort of a Park Cities for Dallas County tribes. The periodic overflowing of the creek created a fertile bottom land for farming. Materials for baskets, mats, and other basic items grew abundantly along the shore. The surrounding woods provided cover for game, while the chalky bluffs that virtually encircled the present lake made excellent campsites.

On one of these bluffs on the west side of the lake, on land now occupied by the H.L. Hunt replica of Mount Vernon, archaeologists have discovered an extensive and varied site known as Humphrey that tells a great deal, if indirectly, about the conditions of Indian life in the first decades of the 19th century. Virtually all of the artifacts found here are foreign to Dallas County: blue flint points and scrapers from somewhere in Central Texas; fragments of Minnesota pipe-stone; brown glaze pots and grinding bowls that may have come from around El Paso; rare combination punch and scraper tools, precursors of the Swiss Army knife, that indicate that these Indians were accustomed to travelling light and with scant access to lithic materials; English gun flints and round rifle balls. All of these items imply that the site was never occupied by a single tribe, but by remnants of assorted bands—Wichita, Caddo, Cherokee, and probably several more—who were struggling to stay out of the reach of the white man and off the reservations. These were difficult times for many Indian tribes. Displacement and forced marches were becoming commonplace. Over on the Elm Fork of the Trinity, General Tarrant and his soldiers, including our own James Beeman, would soon be destroying the last of the Indian villages in the area. So it seems likely that sometime between 1800 and 1840, the front lawn of H.L. Hunt’s mansion was a kind of halfway house for a mixed band of stragglers and renegades.

The farther north you go on White Rock Creek, the poorer the game and vegetation become. The lush bottom land of oak and elm turns into a more open grassland prairie capable of supporting only hardier species. Consequently we find very few archaeological sites north of Northwest Highway, and most of these are small overnight campsites used by buffalo and antelope hunters. The one exception occurs in the vicinity of Old Abrams Road, about a mile from where White Rock Lake currently ends. Known as the Murdock site, after the landowner, it was probably occupied by Wichita Indians sometime between 1200 and 1500 A.D., near the end of the Neo-American period. Like their near contemporaries around the spillway, these Indians raised corn, beans, squash, and melons. Judging from the knives and scrapers uncovered on the site, they were also buffalo hunters, working the nearby draws and branches such as Dixon, Ash, and McKamy. They even made some of their own pottery, a rare occurrence in this region, and appear to have carried on a considerable trade with tribes in East Texas. But the Murdock site marks the end of major Indian migration along White Rock Creek. The terrain to the north was simply too harsh to encourage permanent settlement.

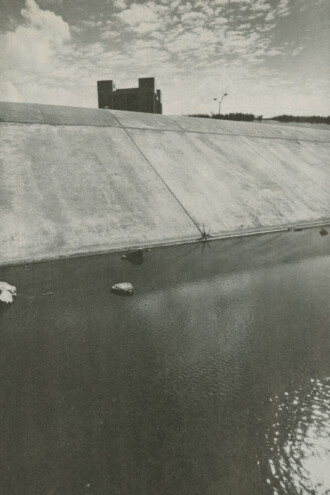

The construction of the White Rock spillway in 1911 was not the first attempt to impound the waters of White Rock Creek. During and after the Civil War, there were a few small grain and flour mills along the lower reaches of the creek, each with its own small dam for power. But if it wasn’t the first attempt, the spillway was certainly the most dramatic and consequential. The reason was drought. Droughts were nothing new in Dallas, of course. They’d occurred periodically throughout the 19th century; they were almost a given. But this one was different. From 1908 to the fall of 1911, almost no rain fell on Dallas. The Elm Fork of the Trinity dried up. The situation became so grave, writes Justin F. Kimbell in Our City—Dallas, “that the insurance companies threatened to withdraw all fire insurance from the city. Special surface mains were laid along Main Street and Pacific Avenue from the river for use in case of necessity. All the artesian wells in the city were put to their utmost pumping capacity and the water from them was put into tank wagons for use as drinking water. Each house placed a zinc tub at the curb and the water wagon went along the streets and filled for use in each home. Of course, all grass, shrubs, and flowers and many trees died.”

The city began drilling additional artesian wells like West Texas wildcatters, but it quickly became clear that the only permanent solution was to build a reservoir. And that was what was done at White Rock Creek. In the summer of 1910, the steam shovels and the mules arrived, and soon most of the Indian village was under several feet of concrete.

By the time the spillway was completed in 1911, the drought was over, but the city continued to use the lake for drinking water until the early ’30s. And then again in the ’50s. The nearly 6 billion gallons impounded not only quenched Dallas’ thirst, they permanently altered the natural environment of the lake. The area that the Indians had occupied for centuries was generally more open and savannah-like, with some grassland and a loose canopy of larger trees leading to the higher terraces where the villages were located. The Humphrey site alone extended nearly 4 miles along the west escarpment to what is now Northwest Highway.

With the arrival of white settlers in the 1840s—cutting the big timber, grazing herds of cattle, controlling the range fires—this area was slowly transformed into a denser, second-growth forest similar to what we now find in the flood plain immediately to the north of the lake. Larger animals like bison and antelope were replaced by domestic sheep and cows.

After the dam was built, as the waters of the lake spread out farther, White Rock became a stopping place for egrets, herons, ducks, and all kinds of other aquatic birds rarely seen in this area. Snakes and turtles flourished in the thick marsh grass along the shore. In a few years a new water ecology was created. And had the public stayed away, White Rock Lake might have become an attractive nature preserve.

But of course the public had no intention of staying away. White Rock Lake was the one attractive body of water around and everybody wanted in. The spillway was scarcely completed before private residences began popping up along the shore, a few of them elegant estates, many more just nondescript cabins and summer houses. Soon fishermen and picnickers had beaten the shoreline flat for sport; overnight, new middens of pop bottles and candy wrappers were created to replace the ancient ones swallowed up by the lake.

And with development came the entrepreneurs with their bizarre schemes for transforming Dallas’ newest natural wonder. In 1927 Colonel S.E. Moss, then water commissioner, proposed creating a Coney Island style amusement park on the lakeshore, complete with roller coasters, Ferris wheels, boat ramps, and, one assumes, a Texas version of the famous Nathan’s hot dog. Lake residents howled and vowed to fight. Moss responded by calling them a bunch of effete bluestocking snobs who were interested only in bridle paths. He threatened to take the whole controversial issue to the people in the 1929 municipal elections, then mysteriously dropped out of the race. His fellow traveler, the flamboyant J. Waddy Tate, continued to press for the Coney Islandizing of White Rock Lake, but stiff opposition from local residents, together with some editorial pummeling by the Dallas Morning News, finally put an end to the idea.

In 1930 the Dallas Park Board assumed control of White Rock Lake and immediately began developing it into a municipal park. Since the mid-1920s the city had maintained a minimum-security jail called the Pea Patch near the White Rock spillway. What better way to upgrade the quality of the area, the board asked, then to use this captive labor as a regular cleanup and maintenance crew? So from 1930 to 1935, most of the city’s certifiably “nonviolent” prisoners were paid a dollar a day to cut brush, grade roads, and build boat ramps and retaining walls. Apparently the local residents didn’t complain so long as the prisoners stayed out of sight—and off the bridle paths.

In 1935 the CCC (Civilian Conservation Corps) established a camp at Winfrey Point, and for the next several years approximately 200 needy men were put to work building piers, culverts, and retaining walls, and otherwise completing the transformation of White Rock Lake from an unmanicured natural area into a public park. Their efforts were so impressive that the anonymous author of the 1940 WPA Guide to Dallas referred to White Rock Lake as “one of the major pleasure resorts of north and central Texas, offering picnicking, horseback riding, fishing, boating, bathing, and aquatic sports, including annual regattas for sailboats and inboard and outboard motor craft. The lake is stocked annually with bass, crappie, bream, channel cat, and other edible fishes. It is also a natural winter habitat for large numbers of ducks, geese, coots, cranes, and other wildfowl, and was formerly dotted with duck blinds used by hunters during the autumn season.” All of this sounds idyllic to anyone who’s attempted a Sunday drive around Lawther, dodging dragsters and flying beer cans, yet one scene undoubtedly foreshadows the other. In less than 30 years a creek had become a lake had become a “major pleasure resort.” And once you’re a “major pleasure resort,” there’s no turning back.

At the start of World War II, most of the CCC workers were inducted, leaving Dallas with an attractive modern facility and no one to use it. As a contribution to the war effort, the city offered the Winfrey Point site to the government to use anyway it saw fit. The government thought for a moment and then suggested turning Winfrey Point into a clinic and rehabilitation center for local prostitutes, who were apparently responsible for an outbreak of VD among recruits at nearby bases. The residents of White Rock lake protested. The government reconsidered and decided that Winfrey Point would be an ideal location for a prisoner of war camp for German soldiers.

Precisely why they chose Dallas, unless for sheer contrast with the fatherland, remains a military secret, yet late in 1943 the remnants of General Rommel’s elite Afrika Corps began arriving in Dallas.

This time there were no protests from the locals. Better Krauts than clap. Each morning the prisoners, many of them engineers, artists, and teachers, were loaded onto trucks and driven to the exposition buildings at Fair Park where they mended tents and clothing, banged the dents out of canteens, and performed other necessary but non-classified tasks. At night they were trucked back to the stockade and, according to old-timers, gardened, painted murals on the barrack walls, and sang “Bei mir bist du schön” through the chain link fence. At the end of the war, the prisoners were returned to Germany. SMU briefly used the abandoned barracks for married-student housing, then turned them back to the city for use as public recreation facilities. Now only one small building remains on Winfrey Point.

A basic problem with most lakes is that they fill up, if not with people and debris, then with silt. White Rock Lake has always had a serious silting problem because all of its watershed lies within the Blackland Prairie. Until the 1880s this land was used primarily for cattle grazing. And the grasses helped to hold the topsoil in place. Later on, with most of this land put into cultivation, usually with cotton and soybeans and other row crops, and with little attention paid to crop rotation and soil conservation, the prairie began to erode rapidly. During each heavy rain, more and more topsoil slid off into the creek and eventually ended up in White Rock Lake.

In the early 1920s the lake had extended as far north as Flag Pole Hill; soon most of this area was covered with 4 to 5 feet of silt. The situation became so critical that in 1937 the city decided that the lake had to be dredged. The Park Department plopped down $21,000 for a special rig, outfitted it, and moved it out to the middle, where a few days later it sank. The crew maintained that the dredge was shoddily constructed; the manufacturer claimed that the crew was drunk and incompetent. Hearings were held but nothing could be proved one way or the other. A few old-timers, recalling that the city had been tampering with the lake for 30 years, concluded that the gods of the creek were merely getting a bit of their own back. The dredge was raised and eventually about 150 acres of the lake were reclaimed, mostly on the northern end. In 1974 the procedure had to be repeated, and now experts are saying that White Rock will have to be dredged once, maybe twice, before 1990.

This time the villain isn’t farming as much as development: the thousands of apartments and townhouses and shopping centers, the miles of paved streets and storm sewers that have been constructed on the upper reaches of the creek since the end of World War II. First the Northwood Community, a small black farming community around Preston and Alpha roads, was annexed in 1958. Then came construction of LBJ and the Dallas North Tollway, encouraging more northern migration. Two years ago Renner was annexed. And on and on. It makes little difference to a creek whether soil is turned over for cotton or condominiums. Both produce runoff and silt. Both can help to strangle a creek, until one day the creek has had enough and floods.

Floods have been almost as commonplace along White Rock Creek as droughts. The early settlers counted on flooding to irrigate the bottom land soils for farming, or else they tried to work around them. In his Diary of 1843, which also carries the more intriguing subtitle of Sketch of a Trip to the Wilderness and Forks of the Trinity River, Edward Parkinson describes the perils of trying to traverse White Rock Creek in the wet season. “We saddled up and proceeded to the fork at White Rock Creek,” he writes, “which we found very difficult from the rain which had fallen, making the bank on the other side one slide of about 30 feet from top to bottom. We were again obliged to dismount and drive the animals over, some of them describing curious mathematical figures from their inexperience in the science of sliding. However, we all got over safe.” (From archives of the Dallas Historical Society.)

White Rock Creek flooded in 1922. It flooded in 1942 and 1949. It flooded in ’57 and ’62. It flooded again in September 1964. Except that this flood wasn’t just another in the series. It was the 100-year flood, the so-called “flood of record” against which all other floods are measured. It was in fact the biggest flood in 120 years, the biggest flood since Parkinson sent his horses slipping and sliding across the creek. It was the deluge. Eleven inches of rain fell in less than eight hours. Lakeside residents, accustomed by now to surprises, reported seeing 6-foot standing waves below the spillway. No one had seen that much water before. All up and down the creek, bridges washed out. Low-lying roads like Abrams and Forest sank almost without a trace. Property owners in North Dallas, who’d cut and filled and built over the flood plain in order to get their air-conditioned living rooms closer to nature, awoke to find their stereos and lawn chairs and Mercedes floating downstream in the general direction of the Trinity. Decks and porches slid off embankments, foundations crumbled. One elderly man was found drowned in the back seat of his car at Northwood Country Club. Another man died on Rowlett Creek in Plano after being swept downstream 4 miles. Homeowners along the creek, some of whom had lost everything, tried to sue the city for negligence. But the city was ready for them. “The flood of September 21 was clearly an act of God,” announced the city attorney. “Nobody could be held responsible.” One wonders how the river spirits received that news.

One positive benefit of the September 1964 disaster was that it convinced just about everyone that the reckless cutting and filling and general tampering along White Rock Creek had to be stopped. The question was how. In the ’50s, the Soil Conservation Commission had recommended creating a series of retention lakes on the upper stretches of the creek. These could be used for flood control during the rainy season and for recreation the rest of the time. This proposal had been turned down as too costly. In 1965 the engineering firm of Forrest and Cotton proposed a cement corridor all the way from North Dallas to White Rock Lake. The Park Board said no, so Forrest and Cotton modified the plan to include only a short section of cement, from Forest Lane just north of LBJ, down to where EDS and Medical City are now. It was a typical political compromise: the developers got what they wanted and the city got a reclaimed stretch of the creek for a greenbelt. But the channel was such an aesthetic horror, tidy, trapezoidal, and sterile, that nobody wanted to see it repeated. When the fight over Bachman Creek erupted several years later, this section of White Rock Creek was used as an example of what not to do. Obviously something more consistent with the history and the flavor of the creek was needed.

The Kessler Plan of 1911 had suggested developing a greenbelt along the entire length of White Rock Creek, and over the years the city had slowly acquired parcels of land for that purpose. Now this activity increased. Valley View and Harry B. Moss parks were acquired for the greenbelt along with other smaller parcels which the city received through donation or by trade. After a century of taking, the city was beginning to give something back. The creek that had been split into small fragments by freeways and spillways and fairways was being put back together again.

Engineers were called in to redraw the flood plain, using the September 1964 deluge as their guide. New development was pushed farther and farther back from the channels, and all requests for cutting and filling were subjected to very strict review. Would the project increase the amount of runoff? Cause flooding downstream? Damage the ecology? Be ugly? Sensible questions that few people in the past had bothered to ask. A creek was meant to be used. That was how it had always been along White Rock.

Of course, no one expects that these regulations will bring back the creek that Beeman and the early settlers saw, when all up and down its length there were “solid masses of Buffalo.” The buffalo are gone and most of the deer and the antelope are playing somewhere else. The vast tall-grass prairie that once covered this region survives now only in tiny, beleaguered patches, museum pieces of a sort. And yet these small patches matter to us spiritually and emotionally, as do those small stretches of White Rock Creek where the water still flows clean and undisturbed; where the tan-white Austin chalk cliffs aren’t bisected by sewer pipes and power lines; where one can still find giant chinquapin oaks and cedar elms, and where, early in the morning, before the cars line up bumper to bumper on Central and LBJ and Hillcrest, one can still watch a heron fish or a fox hunt for rodents in an open field. Very small stretches compared to what once was here, yet where if one is patient and persistent and lucky enough, one may still catch a glimpse of what the Indians saw.

Get our weekly recap

Author