Editor’s Note: This is an accompanying piece to our Lost Dallas package, which you can find here. A shorter version appeared in the print product.

In 1897, Steve Brodie was so famous that his last name was a slang term. You “did a Brodie.” Your pal “took a Brodie.” “Steve Brodie took a chance, why not you?” Brodie, who lived from 1861 until 1901, was a full-fledged international celebrity who had grown up poor in New York’s rough Bowery area, always hustling for cash, always working an angle.

He became instantly famous in 1886 for jumping off the Brooklyn Bridge (as a stunt) and surviving the 150-foot drop into the East River. It had never been done before, and news of his daring feat was breathlessly reported in newspapers around the world. Fame, adulation, and prodigious amounts of cash followed immediately.

Doubts about whether Brodie had actually made the jump or faked it were raised early on (it is now believed he faked it), but Brodie was practically born a self-promoter. He was canny enough to capitalize on his new-found celebrity that he remained in the public consciousness for the rest of his life.

In the fringe 19th-century daredevil-world of people doing dangerous things like leaping from bridges, Brodie was the only person who had managed to parlay a stunt into a highly lucrative career. When Brodie died in 1901 at the very young age of 39—from consumption, in San Antonio—he left an estate valued at what would, today, be worth about $8 million, all of which could be traced directly back to that famed jump off the Brooklyn Bridge.

Even though Brodie was the only person who had made a lot of money indulging in these early “extreme sports,” that didn’t mean others weren’t keen to try to make their own fortunes following in his footsteps. It is here we fast-forward a decade or so from Brodie’s Splash-Heard-‘Round-the-World to Texas, in 1897. Bridge-jumping was a fading fad, but “Steve Brodie” was still a household name. Devotees of the “sport” continued to dive and jump all around the country.

Out here in the Texas hinterlands, a man by the name of J. B. Wilson (“of New York”) was one of those devotees, traveling from town to town, demonstrating his skill as a high-diver, diving from public bridges. In February of 1897 he was in Waco, diving from the suspension bridge into the Brazos River. A crowd estimated at 5,000 showed up to watch the successful high-dive into what Wilson later claimed was only 18 inches of water. Wilson’s next stop? Dallas.

On March 17, 1897, a one-sentence blurb appeared in the pages of The Dallas Morning News, under the headline “A Bridge–Jumper”:

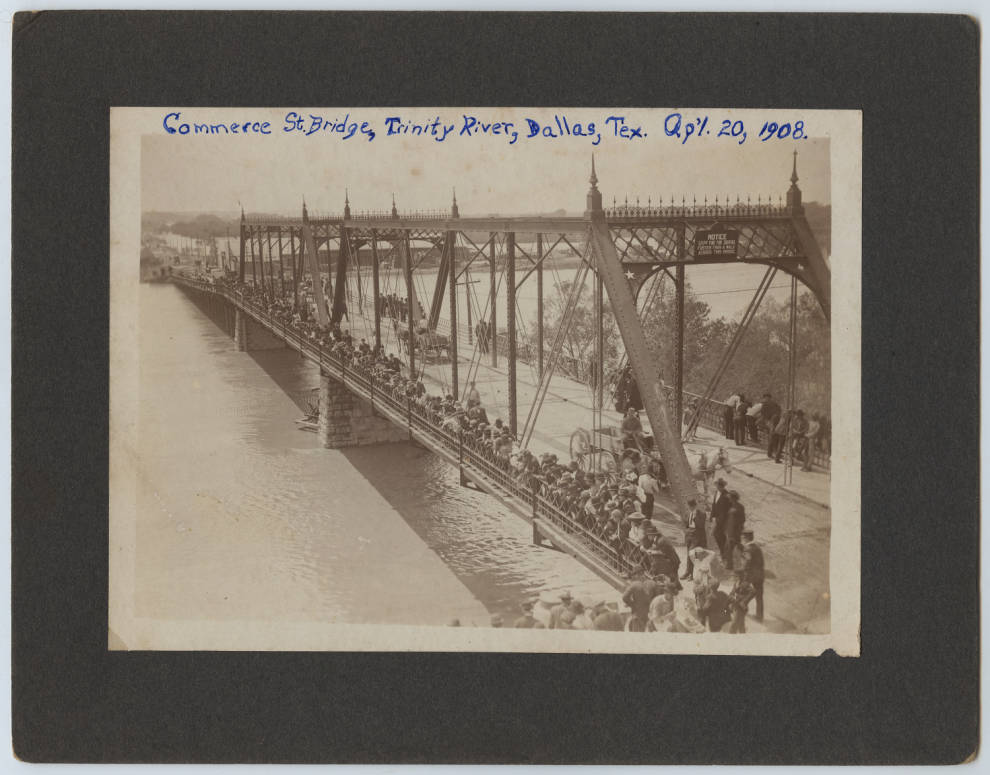

The prospect of seeing something as exotic as a high-dive in land-locked Dallas—along with the potential of watching some crazy person jump to a grisly demise before their very eyes—assured a large Sunday-afternoon gathering of curious looky-loos. The crowd of 6,000 to 7,000 was described by The Dallas Morning News as “young and old, black and white, rich and poor, saint and sinner.” People packed the Commerce Street Bridge and the nearby Trinity-spanning railroad trestle. They lined both banks of the Trinity River. They climbed onto roofs of nearby houses and into treetops for a better view. Others amassed in boats on the river. It was the largest crowd to converge on the Trinity since 1893, when the steamer H. A. Harvey, Jr. triumphantly arrived from its long voyage up the river from the Gulf.

The highest point of the Commerce Street Bridge, built in 1890, was about 65 feet. Luckily for professional diver J.B. Wilson, heavy rains had fallen steadily in the days leading up to his advertised jump. Even though he swore he could make a successful dive into a mere foot-and-a-half of water, it was estimated that the river’s depth that day was a healthy 18 to 20 feet in the channel under the bridge (this was before the Trinity River was re-channeled; it was a stone’s throw from what is now Dealey Plaza).

So what happened? Did he perish or succeed? Luckily, we have a handful of long, detailed, and dryly amusing accounts of this event from The Dallas Morning News. These were written without a byline, but the writer was a wonderfully talented and observant newspaperman who referred to himself—one can only assume sardonically— as the News’ “marine reporter.” His two main accounts of this event provide the facts and, more importantly, the color surrounding this surprisingly well-attended high-dive exhibition.

At the advertised hour, J. B. Wilson—who was calling himself “the champion high-diver of the world”—arrived, decked out in a diving costume that resembled an acrobat’s leotard. The News’ “marine reporter” described Wilson’s appearance thusly:

The assembled crowd was ready and eager to watch the professional high-diver ply his trade, but an unexpected announcement was made first. Apparently Mr. Wilson would not—could not—make his leap until he had collected monetary donations for his efforts. There were catcalls from the crowd and much grumbling as Wilson passed through the spectators with a cigar box, soliciting nickels and dimes from the throng. He worked the crowd strenuously for an hour and fifteen minutes, determined to collect at least enough money to cover his expenses.

his trade, but an unexpected announcement was made first. Apparently Mr. Wilson would not—could not—make his leap until he had collected monetary donations for his efforts. There were catcalls from the crowd and much grumbling as Wilson passed through the spectators with a cigar box, soliciting nickels and dimes from the throng. He worked the crowd strenuously for an hour and fifteen minutes, determined to collect at least enough money to cover his expenses.

When he had finished passing the plate, he counted out the coins, only to discover that he had taken in a grand total of $13 (the equivalent of about $390 in today’s money). The News’ reporter wrote that “a great wave of dispassionate disgust swept across [Wilson’s] mobile face and took refuge there.”

Bitter and unhappy, Wilson announced that he would not dive from the top of the bridge after all; it just wasn’t worth his while for such a paltry show of support. He would, instead, dive from the lowest rail, a height of about 35 feet rather than the 65 feet he’d promised. The crowd was not amused.

A young man who had positioned himself at the very top of the bridge shouted down to Wilson, derisively, “Come up here. Oh come up here and jump!” Wilson replied to the young man 30 feet above him, “Not for $13. If you want a dive from up there, why, just dive yourself.”

“You’re not the only turtle in the tank!” the heckler jeered back.

And at that, Wilson dove head-first into the rain-swollen river, showing off his fancy diving and impressive swimming skills. As the News’ reporter wrote, the response from the crowd was not unlike that which met the Mighty Casey’s anticlimactic Mudville whiff:

As a wave of angered disappointment swept through a crowd that felt it had been cheated, something unanticipated happened: the “turtle in the tank” guy suddenly jumped from the top of the bridge, still in his street clothes, plunging feet-first into the Trinity River, 65 feet below. The shocked crowd roared with applause as young Arch Sexton— a 22-year-old Illinois native who had come to Dallas as a child and was currently working as a candy-maker—saved the day and became the hero of the hour.

Sexton later told reporters that he had read about Wilson’s advertised dive and had decided it wasn’t such a big deal. He went to the river that day with plans to jump from the bridge; he had never done anything like that before, but he said he was “determined that the honor of Dallas should be upheld.” He told The News that he learned to swim and dive as a boy in the lazy White Rock Creek (which the News’ reporter sarcastically described as “the seething waters of the treacherous White Rock”).

Young Sexton was possessed of moxie, daring, and brash enthusiasm—some might add “arrogance” in there as well. After his successful leap, he immediately proclaimed himself the “world champion.” Still stunned, the out-classed Wilson issued a challenge to try to reclaim the (somewhat dubious) title which had been snatched from him so unexpectedly, but Sexton had bigger fish to fry: he set his sights on Mr. Big himself, Steve Brodie (whose alleged jump from the Brooklyn Bridge a decade earlier was from a distance more than twice as high as Sexton’s had been). As Sexton’s plans of world bridge-jumping domination (and a Brodie-like fortune) spun in his head, a damp and vanquished Wilson left town quietly, heading down the line to the next bridge that would have him.

“I am the champion bridge jumper of the world. I am anxious to do business with Steve Brodie, who claims to be the champion of America … Brodie is the man I’m after. Let the others go and make records and then I’ll consider their propositions.”

But Brodie never responded to Sexton’s challenge. It was reported that he had retired from bridge-jumping and was focusing on his famous New York bar and his career as an actor (incidentally, at the time of this Dallas jump, Brodie was appearing in a stage production called “The Bowery” in which he played himself, going so far as to somehow recreate the famous jump onstage).

Unfazed by silence from the Brodie camp, Sexton began training in Illinois. He was ready to take on any serious challengers (so long as they weren’t “small-fry”) and to be a sterling bridge-jumping ambassador for Texas.

“I’ll see to it that the reputation of Texas does not suffer abroad. I am the champion high–jumper of the world and I don’t care a cent who knows it.”

A month after his triumph against Wilson, Sexton was back in Dallas and announced that he would again jump from the top of the Commerce Street Bridge:

And jump again he did, on April 18, 1897. This time it was just to show he still “had it” (he also probably hoped he might scrounge up some big-fry challengers and a manager or financial backer).

The scene was, again, the Commerce Street Bridge. This time the crowd was much smaller, but a still-impressive 1,500 people showed up to watch Sexton show off his high-jumping skills and another young man show off his high-diving skills. (It’s important to note that Sexton made it clear that he was a high-jumper, not a high-diver. As he told a reporter after the contest with Wilson, “He is a diver. I’m a jumper. I would not dive for any man’s money.”)

As Wilson had done, Sexton and his partner walked among the crowd collecting any donations people wished to throw their way but, unlike the angry response Wilson received, the spectators didn’t seem to mind this passing-of-the-plate. Even though the offerings were meager ($5.10), the young men happily thanked the people and quickly got down to business.

The diver, 19-year-old Dallas teen Nick Miller, dove off a springboard which had been attached to the bridge’s railing into what was estimated to be about eight feet of water. His dive drew an appreciative ovation from the crowd.

The jumper—the supremely confident champion, A. B. Sexton, clad in his new jumping outfit—climbed to the top of the bridge and, after surveying the crowd for a full, theatrical 95 seconds, he gestured with a flourish, and then dropped “like shot … his feet hit[ting] the water in advance of the balance of his anatomy.” When he bobbed back to the surface, he swam gracefully toward the riverbank.

“As he was nearing the shore Sexton caught sight of a water snake basking in the sunlight in the bosom of the river. He caught the snake and came ashore with the wriggling trophy of his adventure. An excited individual handed him a quarter just as he reached dry land.”

And that was the last mention of A. B. Sexton, the self-proclaimed “High-Jumping Champion of the World”… until a small article appeared in the pages of The Dallas Morning News in March of 1917, exactly 20 years after Sexton’s impetuous jump from the top of the Commerce Street Bridge. In the intervening years he had moved back to Illinois, married, started a family, served for a time as a city marshal, and had run a small-town movie theater, but it was clear that he considered that leap 20 years previous to be his life’s greatest accomplishment. He told The News that he had carried the original newspaper account of his daring feat for all those years. It was one of his prized possessions.

Arch Sexton died in 1935 at the age of 61. He might not have become a household name or made a fortune from his jump like Steve Brodie had, but at least 6,000 awed Dallasites had witnessed his leap, while no one, really, could swear they had actually seen Brodie’s purported world-famous jump. We’re willing to concede that Sexton might not have been the “high-jumping champion of the world,” but he was certainly the “high-jumping champion of Dallas.”

And as far as we know, that record still stands.

Paula Bosse is a Dallas-based writer and editor. She is the founder of Flashback Dallas, and can be reached at [email protected].

In 1897, Steve Brodie was so famous that his last name was a slang term. You “did a Brodie.” Your pal “took a Brodie.” “Steve Brodie took a chance, why not you?” Brodie, who lived from 1861 until 1901, was a full-fledged international celebrity who had grown up poor in New York’s rough Bowery area, always hustling for cash, always working an angle.

He became instantly famous in 1886 for jumping off the Brooklyn Bridge (as a stunt) and surviving the 150-foot drop into the East River. It had never been done before, and news of his daring feat was breathlessly reported in newspapers around the world. Fame, adulation, and prodigious amounts of cash followed immediately.

Doubts about whether Brodie had actually made the jump or faked it were raised early on (it is now believed he faked it), but Brodie was practically born a self-promoter. He was canny enough to capitalize on his new-found celebrity that he remained in the public consciousness for the rest of his life.

In the fringe 19th-century daredevil-world of people doing dangerous things like leaping from bridges, Brodie was the only person who had managed to parlay a stunt into a highly lucrative career. When Brodie died in 1901 at the very young age of 39—from consumption, in San Antonio—he left an estate valued at what would, today, be worth about $8 million, all of which could be traced directly back to that famed jump off the Brooklyn Bridge.

Even though Brodie was the only person who had made a lot of money indulging in these early “extreme sports,” that didn’t mean others weren’t keen to try to make their own fortunes following in his footsteps. It is here we fast-forward a decade or so from Brodie’s Splash-Heard-‘Round-the-World to Texas, in 1897. Bridge-jumping was a fading fad, but “Steve Brodie” was still a household name. Devotees of the “sport” continued to dive and jump all around the country.

Out here in the Texas hinterlands, a man by the name of J. B. Wilson (“of New York”) was one of those devotees, traveling from town to town, demonstrating his skill as a high-diver, diving from public bridges. In February of 1897 he was in Waco, diving from the suspension bridge into the Brazos River. A crowd estimated at 5,000 showed up to watch the successful high-dive into what Wilson later claimed was only 18 inches of water. Wilson’s next stop? Dallas.

On March 17, 1897, a one-sentence blurb appeared in the pages of The Dallas Morning News, under the headline “A Bridge–Jumper”:

“A disciple of Steve Brodie of Bowery fame, who won notoriety by leaping from the Brooklyn bridge, is in the city, and says he will jump from the Commerce street bridge into the Trinity river next Sunday afternoon.”

The prospect of seeing something as exotic as a high-dive in land-locked Dallas—along with the potential of watching some crazy person jump to a grisly demise before their very eyes—assured a large Sunday-afternoon gathering of curious looky-loos. The crowd of 6,000 to 7,000 was described by The Dallas Morning News as “young and old, black and white, rich and poor, saint and sinner.” People packed the Commerce Street Bridge and the nearby Trinity-spanning railroad trestle. They lined both banks of the Trinity River. They climbed onto roofs of nearby houses and into treetops for a better view. Others amassed in boats on the river. It was the largest crowd to converge on the Trinity since 1893, when the steamer H. A. Harvey, Jr. triumphantly arrived from its long voyage up the river from the Gulf.

The highest point of the Commerce Street Bridge, built in 1890, was about 65 feet. Luckily for professional diver J.B. Wilson, heavy rains had fallen steadily in the days leading up to his advertised jump. Even though he swore he could make a successful dive into a mere foot-and-a-half of water, it was estimated that the river’s depth that day was a healthy 18 to 20 feet in the channel under the bridge (this was before the Trinity River was re-channeled; it was a stone’s throw from what is now Dealey Plaza).

So what happened? Did he perish or succeed? Luckily, we have a handful of long, detailed, and dryly amusing accounts of this event from The Dallas Morning News. These were written without a byline, but the writer was a wonderfully talented and observant newspaperman who referred to himself—one can only assume sardonically— as the News’ “marine reporter.” His two main accounts of this event provide the facts and, more importantly, the color surrounding this surprisingly well-attended high-dive exhibition.

At the advertised hour, J. B. Wilson—who was calling himself “the champion high-diver of the world”—arrived, decked out in a diving costume that resembled an acrobat’s leotard. The News’ “marine reporter” described Wilson’s appearance thusly:

“His golden hair was cut bias and his feet were shoeless, but not stockingless. He is a supple-looking young fellow with a pleasant face, a frank countenance and an exceedingly nimble tongue.”

The assembled crowd was ready and eager to watch the professional high-diver ply

his trade, but an unexpected announcement was made first. Apparently Mr. Wilson would not—could not—make his leap until he had collected monetary donations for his efforts. There were catcalls from the crowd and much grumbling as Wilson passed through the spectators with a cigar box, soliciting nickels and dimes from the throng. He worked the crowd strenuously for an hour and fifteen minutes, determined to collect at least enough money to cover his expenses.

his trade, but an unexpected announcement was made first. Apparently Mr. Wilson would not—could not—make his leap until he had collected monetary donations for his efforts. There were catcalls from the crowd and much grumbling as Wilson passed through the spectators with a cigar box, soliciting nickels and dimes from the throng. He worked the crowd strenuously for an hour and fifteen minutes, determined to collect at least enough money to cover his expenses.When he had finished passing the plate, he counted out the coins, only to discover that he had taken in a grand total of $13 (the equivalent of about $390 in today’s money). The News’ reporter wrote that “a great wave of dispassionate disgust swept across [Wilson’s] mobile face and took refuge there.”

Bitter and unhappy, Wilson announced that he would not dive from the top of the bridge after all; it just wasn’t worth his while for such a paltry show of support. He would, instead, dive from the lowest rail, a height of about 35 feet rather than the 65 feet he’d promised. The crowd was not amused.

A young man who had positioned himself at the very top of the bridge shouted down to Wilson, derisively, “Come up here. Oh come up here and jump!” Wilson replied to the young man 30 feet above him, “Not for $13. If you want a dive from up there, why, just dive yourself.”

“You’re not the only turtle in the tank!” the heckler jeered back.

And at that, Wilson dove head-first into the rain-swollen river, showing off his fancy diving and impressive swimming skills. As the News’ reporter wrote, the response from the crowd was not unlike that which met the Mighty Casey’s anticlimactic Mudville whiff:

“Wild salvos of applause did not ring in his ears, nor did the glad acclaims of his countrymen awaken the echoes of the surrounding country or startle the frogs in their nests. There was a cold, icy hauteur concealed somewhere in that mighty throng that chilled the marrow in one’s bones and coagulated the rich red blood in one’s veins.”

As a wave of angered disappointment swept through a crowd that felt it had been cheated, something unanticipated happened: the “turtle in the tank” guy suddenly jumped from the top of the bridge, still in his street clothes, plunging feet-first into the Trinity River, 65 feet below. The shocked crowd roared with applause as young Arch Sexton— a 22-year-old Illinois native who had come to Dallas as a child and was currently working as a candy-maker—saved the day and became the hero of the hour.

Sexton later told reporters that he had read about Wilson’s advertised dive and had decided it wasn’t such a big deal. He went to the river that day with plans to jump from the bridge; he had never done anything like that before, but he said he was “determined that the honor of Dallas should be upheld.” He told The News that he learned to swim and dive as a boy in the lazy White Rock Creek (which the News’ reporter sarcastically described as “the seething waters of the treacherous White Rock”).

Young Sexton was possessed of moxie, daring, and brash enthusiasm—some might add “arrogance” in there as well. After his successful leap, he immediately proclaimed himself the “world champion.” Still stunned, the out-classed Wilson issued a challenge to try to reclaim the (somewhat dubious) title which had been snatched from him so unexpectedly, but Sexton had bigger fish to fry: he set his sights on Mr. Big himself, Steve Brodie (whose alleged jump from the Brooklyn Bridge a decade earlier was from a distance more than twice as high as Sexton’s had been). As Sexton’s plans of world bridge-jumping domination (and a Brodie-like fortune) spun in his head, a damp and vanquished Wilson left town quietly, heading down the line to the next bridge that would have him.

“I am the champion bridge jumper of the world. I am anxious to do business with Steve Brodie, who claims to be the champion of America … Brodie is the man I’m after. Let the others go and make records and then I’ll consider their propositions.”

But Brodie never responded to Sexton’s challenge. It was reported that he had retired from bridge-jumping and was focusing on his famous New York bar and his career as an actor (incidentally, at the time of this Dallas jump, Brodie was appearing in a stage production called “The Bowery” in which he played himself, going so far as to somehow recreate the famous jump onstage).

Unfazed by silence from the Brodie camp, Sexton began training in Illinois. He was ready to take on any serious challengers (so long as they weren’t “small-fry”) and to be a sterling bridge-jumping ambassador for Texas.

“I’ll see to it that the reputation of Texas does not suffer abroad. I am the champion high–jumper of the world and I don’t care a cent who knows it.”

A month after his triumph against Wilson, Sexton was back in Dallas and announced that he would again jump from the top of the Commerce Street Bridge:

“The world’s record is still in Dallas. I hold it … I must keep in practice for Brodie and the eastern jumpers. They are a lot of ‘has–beens,’ who do all their jumping in the newspapers … I am ready to meet any high jumper in the civilized world. On Sunday I will jump again, just to demonstrate to the people that I am the champion of the world.”

And jump again he did, on April 18, 1897. This time it was just to show he still “had it” (he also probably hoped he might scrounge up some big-fry challengers and a manager or financial backer).

“I’ll see to it that the reputation of Texas does not suffer abroad. I am the champion high–jumper of the world and I don’t care a cent who knows it.”

Arch Sexton

The scene was, again, the Commerce Street Bridge. This time the crowd was much smaller, but a still-impressive 1,500 people showed up to watch Sexton show off his high-jumping skills and another young man show off his high-diving skills. (It’s important to note that Sexton made it clear that he was a high-jumper, not a high-diver. As he told a reporter after the contest with Wilson, “He is a diver. I’m a jumper. I would not dive for any man’s money.”)

As Wilson had done, Sexton and his partner walked among the crowd collecting any donations people wished to throw their way but, unlike the angry response Wilson received, the spectators didn’t seem to mind this passing-of-the-plate. Even though the offerings were meager ($5.10), the young men happily thanked the people and quickly got down to business.

The diver, 19-year-old Dallas teen Nick Miller, dove off a springboard which had been attached to the bridge’s railing into what was estimated to be about eight feet of water. His dive drew an appreciative ovation from the crowd.

The jumper—the supremely confident champion, A. B. Sexton, clad in his new jumping outfit—climbed to the top of the bridge and, after surveying the crowd for a full, theatrical 95 seconds, he gestured with a flourish, and then dropped “like shot … his feet hit[ting] the water in advance of the balance of his anatomy.” When he bobbed back to the surface, he swam gracefully toward the riverbank.

“As he was nearing the shore Sexton caught sight of a water snake basking in the sunlight in the bosom of the river. He caught the snake and came ashore with the wriggling trophy of his adventure. An excited individual handed him a quarter just as he reached dry land.”

And that was the last mention of A. B. Sexton, the self-proclaimed “High-Jumping Champion of the World”… until a small article appeared in the pages of The Dallas Morning News in March of 1917, exactly 20 years after Sexton’s impetuous jump from the top of the Commerce Street Bridge. In the intervening years he had moved back to Illinois, married, started a family, served for a time as a city marshal, and had run a small-town movie theater, but it was clear that he considered that leap 20 years previous to be his life’s greatest accomplishment. He told The News that he had carried the original newspaper account of his daring feat for all those years. It was one of his prized possessions.

Arch Sexton died in 1935 at the age of 61. He might not have become a household name or made a fortune from his jump like Steve Brodie had, but at least 6,000 awed Dallasites had witnessed his leap, while no one, really, could swear they had actually seen Brodie’s purported world-famous jump. We’re willing to concede that Sexton might not have been the “high-jumping champion of the world,” but he was certainly the “high-jumping champion of Dallas.”

And as far as we know, that record still stands.

Paula Bosse is a Dallas-based writer and editor. She is the founder of Flashback Dallas, and can be reached at [email protected].