Last month the Dallas Morning News ran three excerpts related to Dallas from Edward McPherson’s new book, The History of the Future. The first of the series begins in Dallas 318 million years ago, a seemingly lifeless vacuum until the arrival of John Neely Bryan in 1841. Three short paragraphs later, this appears:

Dallas came from nothing. Unlike surrounding areas, it was not a camp for Native Americans or prehistoric men. Dig and you find few artifacts.

McPherson, to some degree, is having us on. By the end of that same paragraph, he writes:

Dallas wasn’t there until — suddenly — it was, called forth in the minds of white men.

But back to that first quote; the second one seems plausible enough. Is he categorically saying Dallas hasn’t many artifacts, and that their regional paucity is proof there were no camps of native peoples? Or is this a well-crafted provocation of obvious untruth? Either way, it raises an important question: how many people know enough about Dallas’ pre-John Neely Bryan history to know McPherson’s statement is erroneous?

How many people, for example, know about the 2,617 chipped lithic artifacts, 11 ground or pecked stone tools, 21 ceramic vessel fragments, 66 fragments of fired or burned clay, 2,850 grams of thermally altered rock, 96 faunal remains, and two charred botanical fragments recently unearthed prior to and during the construction of the Texas Horse Park in the Great Trinity Forest? Without question, the nearly 3,000 artifacts are strong evidence for a camp(s) of prehistoric humans engaged in a variety of activities. The possible reasons these artifacts have not received news coverage — the medium by which most people would know about the find — will be addressed a little later on. It’s more a city omission than a mainstream media one.

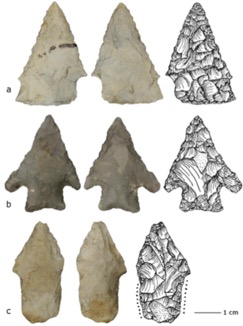

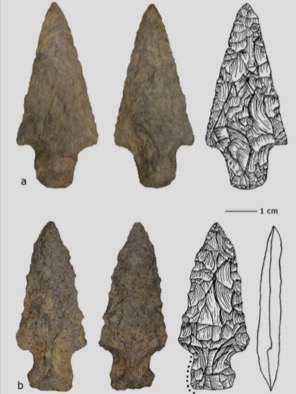

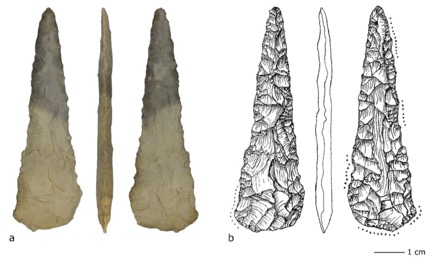

First, some images to prove that Dallas has artifacts.

In decades past, the Dallas Morning News frequently covered area archeological discoveries. A few hours researching their archives through the Dallas Central Library’s database revealed sites all over the city. Here are a few highlights:

1920 Lagow Sand Pit, near Fair Park. Skeletal remains of a prehistoric man found in the fossiliferous part of the pit along with the skull of an extinct camel.

1941 White Rock Lake Spillway. Two ancient graves found near the spillway after area flooding. In one of the graves, a man, woman, and baby were jointly buried. The baby rested on the left arm of the woman and had a 29-inch-necklace made of 81 beads made of polished bird bone around its neck bones.

1961 Trinity River. An Irving man, Alvah White, found more than 300 arrowheads “representing many tribes” by working a big sand deposit near the original confluence of the West and Elm forks of the Trinity.

1972 Intersection of I-30 and LBJ Expressway. Two police officers found hundreds of artifacts, dating back 5,000 years, in a gravel pit northwest of the busy intersection: 1,000 arrowheads, grindstones, tomahawks, pottery, teeth, and five human skeletons.

Ca. 1978 Dallas Soccer Fields. After people found artifacts on soccer fields around Dallas, it prompted an area archeologist to ask the city where it was getting its sand. The sand—and all the artifacts—originated from the same pit near downtown; the Parks Department knew what was happening but didn’t inform the city.

And most recently, but not reported by the Dallas Morning News:

2015 Texas Horse Park, Great Trinity Forest. A cultural resources survey is completed within a 266-acre track owned by the city and operated as an equestrian facility. Artifacts found during the investigation are deposited in Austin at the Texas Archeological Research Laboratory (TARL). The survey is not yet publicly available and artifacts can only be viewed at TARL by appointment.

Questions at this junction might be: where is Lagow Man now? Where is the bird-bead necklace? The arrowheads? The grindstones? Hard to say, before state and federal laws were established in the 1960s, there were few protections for archeological sites and artifacts. Under the Antiquities Code of Texas, enacted in 1969, major projects — highways, roads, reservoirs, horse parks — require political subdivisions of the state (cities, counties, river authorities) to “notify the Texas Historical Commission of ground-disturbing activity on public land and work affecting publicly owned historic buildings.”

In a nutshell, that is why the most recent Dallas artifacts were recovered. The city is required by law to conduct a professional cultural resources survey and to deposit artifacts in a state-approved facility under the Antiquities Code. The city is not required, however, to mount exhibitions or make public statements. (And without some substantial digging, the media can’t report on something it doesn’t know about.) Some cities, like San Antonio, elect to broadcast area finds as a matter of public interest.

Prior to construction of the Texas Horse Park, there was a high probability artifacts would be recovered. That’s because once THC had been notified of project, it conducted research using a database called the Texas Archeological Sites Atlas. THC’s database revealed 14 previously recorded cultural sites in the area. Some of that information came from surveys for other projects, and some from sites recorded by the Dallas Archeological Society, a long-lived organization that disbanded about five years ago.

The DAS formed in the late 1930s. Two of its most prominent early members, Forrest Kirkland, an artist, and Robert King Harris, a locomotive engineer, recorded area sites and wrote about artifact finds. Articles of the society’s members were published in its periodical, The Record, a publication archeologist Tim Dalbey describes as “the only source of public local information about archeology up into the 1970s.”

The 1940s-era survey work by Harris was the basis of a city-funded project in 1978. The $10,000 project, conducted by SMU archeology students, aimed to create a database of prehistoric sites in Dallas for use by city planners and builders (at the time, thought to be in the hundreds). Dallas’ chief preservation planner Mark Doty said in an email he isn’t aware of an archeological database, adding, “we do not have that for historic overlays and districts.”

The same inquiry was made among other city departments with no response. If the 1978 database does exist, the public most likely wouldn’t be allowed access for reasons of guarding sites against potential looting and vandalism (precisely who the looters and vandals might be is open to qualification). There are other ways to learn about local sites and view artifacts without jeopardizing them, but most require travel outside the city.

As mentioned earlier, the artifacts excavated near the Texas Horse Park can be viewed at TARL by appointment only, located on the campus of UT Austin. Harris’ maps of area archeological sites and other papers are housed at the Smithsonian Institute’s National Anthropological Archives in Suitland, Maryland. And the DAS periodical, The Record, can be found at SMU, UTA, and UNT libraries as non-circulating “missing, scattered issues.”

Dallas is big, but is it deep? How far back in the past are we willing to look for continuity as a human family? I think McPherson is provoking us into this line of inquiry with his cultural history of Dallas tropes and factual inaccuracies. But if the public doesn’t know where to look for information—which is most likely found in the interstices of conscious omission—how can we possibly act in our best interests?

More construction is coming to the Great Trinity Forest and the floodway. I would wager most people would not want a park of concrete and asphalt if it came at the expensive of cultural resources that few even know exist.

Special thanks to Tim Dalbey for his insights on area archeology, and the THC for providing the most recent version of the Texas Horse Park cultural resources survey.