Much has been made of the lack of hospital beds in North Texas during the recent COVID-19 surge. The dearth of pediatric ICU beds at local children’s hospitals made it on CNN, with Dallas County Judge Clay Jenkins making dark predictions like, “Your child will wait for another child to die” before they receive care. Things have gotten so bleak that Jenkins has taken to tweeting out the number of available ICU beds in the region each day.

But the explosion of COVID-19 cases over the past six weeks still hasn’t reached the peak numbers North Texas saw in January. So why are we seeing dire headlines about the lack of beds when COVID-19 infections were statistically worse earlier this year?

Several factors beyond COVID-19 cases are contributing to the lack of bed space. One is the overall hospital census, which is greater than during the peak of COVID-19 this winter. Many were afraid to call 911 during the earlier waves, and heart attack victims, stroke victims, and other emergencies never made it to the hospital. Emergency service companies reported a 35 percent decrease in emergency calls and an increased number of dead arrivals at different stages during the pandemic. Patients are now more comfortable coming to the hospital, and, after months of delayed care, they are looking to catch up on missed appointments, procedures, and treatments. After the winter surge, hospitals have stayed full with non-COVID-19 patients.

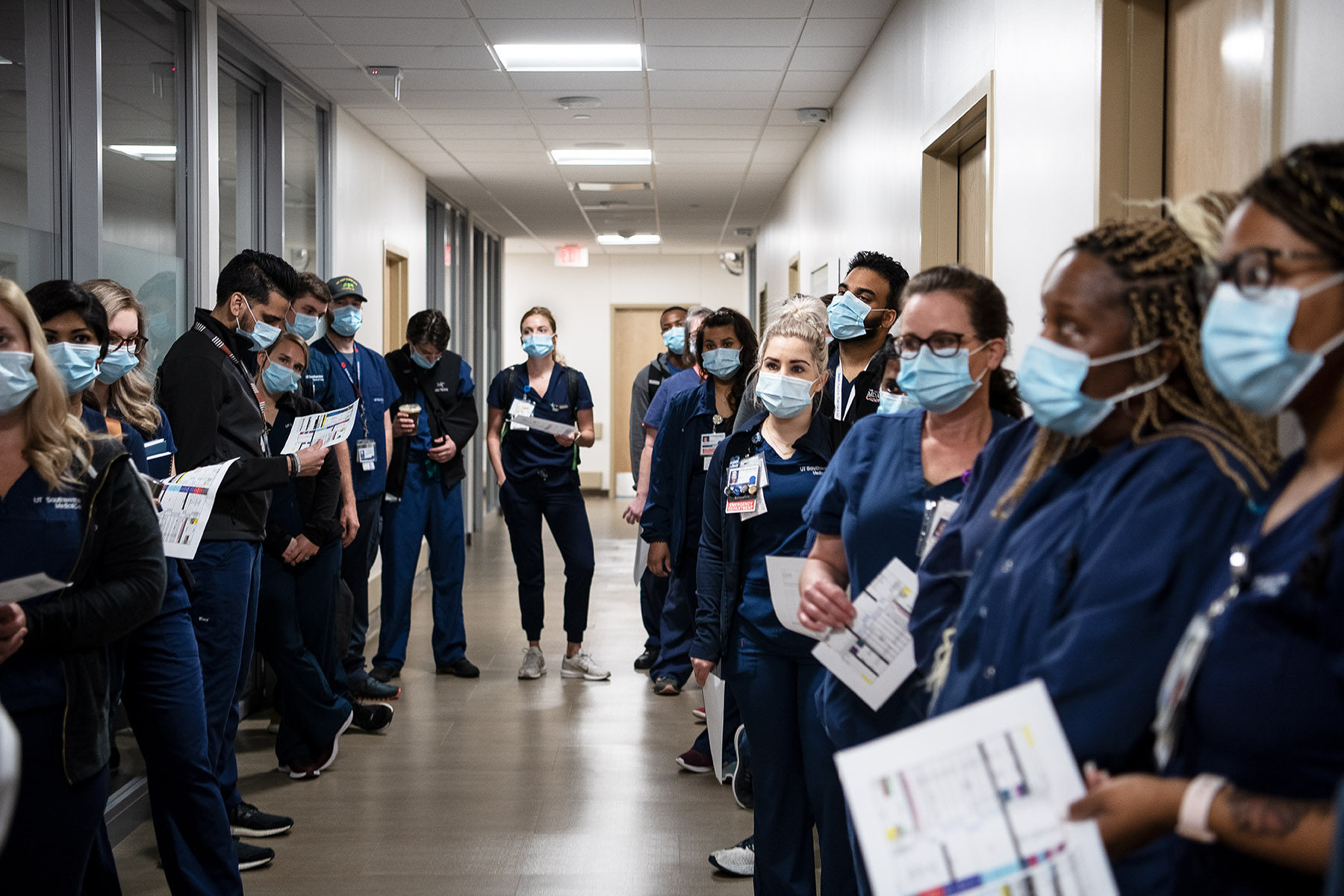

Another issue is the staff shortage. A hospital may have available space, but if there isn’t staff to attend to those patients, a patient can’t occupy that bed. During the first waves of COVID-19, different regions of the country experienced surges at different times. That meant hospitals could bring in traveling caregivers to staff the beds. “There is no rescue cavalry, and it is so bad everywhere, that no one available to come to our aide,” says Dr. Mark Casanova, a palliative care physician with Baylor Scott & White and a member of the Texas Medical Association’s COVID-19 Task Force. (He was also the president of the Dallas County Medical Society in 2020 during the pandemic.)

Texas nurses went to New York and physicians headed to the Rio Grande Valley at different points in 2020. But this summer, the entire country is being inundated with new cases, meaning there is no available staff from around the country to attend to Texas patients. The state had three large traveling nurse contracts in January, but they are no longer in place. “Having a bed without the proper staff is problematic,” says Steve Love, the CEO of the Dallas Fort Worth Hospital Council. “The other important thing to remember is the needed skill set matched with the staff. We need critical care personnel and the underlying support staff, and not all staff possess those needed skill sets.”

Burnout has been another factor in the reduced hospital capacity. An American Medical Association study found that out of more than 20,000 caregivers, 61 percent felt high fear of exposing themselves or their families to COVID-19. About 38 percent self-reported experiencing anxiety or depression. Meanwhile, 43 percent suffered from too much work, and 49 percent experienced burnout. Childcare concerns have also led parents (especially women) to leave the workforce or cut back their hours.

Casanova also notes that the delta strain is more contagious and behaves differently from the original, resulting in a higher rate of hospitalizations compared to the earlier versions of the virus. Delta is also impacting healthier patients more frequently than last year. COVID-19 patients make up about 50 percent of ICU patients in North Texas.

“The delta strain is a real bad mama jama and has us in a world of hurt right now,” Casanova says. “Forecasting is ominous.”

On the pediatric front, increased mobility and a near complete lack of flu season last winter have resulted in a resurgence of flu and respiratory syncytial virus, a common respiratory virus that usually impacts infants and can result in hospitalization. Summer is usually a slow period for children’s hospitals. Still, the number of hospitalized RSV patients is equivalent to the height of flu season, leaving fewer beds available for rising COVID-19 patients.

UT Southwestern’s latest forecasting predicts that the delta surge will exceed the January peak in new cases and hospitalizations later this fall. Hospital volumes have already gone up 96 percent in two weeks and 414 percent in the past month. UTSW’s models predict 1,800 new daily cases and 1,500 concurrent hospitalizations in Dallas County by the end of the month without any significant changes to vaccination rates or other behavior. But mask mandates, social distancing, and increased vaccinations could bring us closer to the end of the current peak, the models say. If Dallas County returns to the precautions taken last fall, there may be very few cases per day by the end of October.

Love, of the hospital council, recounts what an infectious disease physician told him earlier this summer: “If a person is unvaccinated in Texas today, there are only two things that will happen. They will decide to immediately get vaccinated, or they will get the delta variant.”