The dance and the football game were in October, but Thomas Jefferson High School has been waiting for its true homecoming for more than three years. A tornado blew apart the campus in October 2019, displacing the community to another school in another neighborhood 9 miles away. The students, teachers, and staff were disrupted again the next year by the coronavirus pandemic.

But on Monday, the TJ community returned to a fully rebuilt campus on Walnut Hill Lane.

“What’s that phrase from Dorothy? There’s no place like home?” says teacher and senior class sponsor Cathleen Cadigan. “We finally get to click our heels.”

But even before their high school experience was upended by a twister and a pandemic, many TJ students were already well-acquainted with the concept of sudden and unexpected displacement. Ninety-seven percent of Thomas Jefferson’s 1,450 students are Latino, and 67 percent are considered “emerging bilingual.” Of those, 212 are officially classified as “newcomers,” meaning they have been in the United States for three years or fewer. That is the highest percentage of any high school in Dallas ISD.

Most hail from the arid plains of Mexico or the tropical hills of Central America’s “Northern Triangle,” made up of Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala. They have settled with friends and family in the dense maze of apartments beneath the Love Field approach pattern just north of Bachman Lake. Many TJ students, or their parents, left their countries of origin on treacherous northward journeys, often to escape gang violence, extortion, or crushing poverty, usually never to return.

“I came here seven years ago from Honduras,” Dennilson Duarte, a former TJ soccer player, told me shortly after the storm in 2019. He graduated in 2020. “Thomas Jefferson and Cary Middle School has been my home for the past seven years, and losing them feels like I’m losing my home again.”

Assistant Principal Erika Vigil oversees the Dallas International Academy, a district pilot program started at TJ this year to help newcomers assimilate. She says she regularly meets kids who boarded a bus at the border and “got off when the crowd got off.” Some have never seen a lunch line before. “Even for the kids who have been here for six months, they’re still kinda like deer in the headlights every day,” she says.“That little sense of familiarity [was] literally uprooted, so it [was] almost like a re-immigration.”

I began documenting the lives of these immigrant students five years ago as part of an ongoing project called The Time We Have Here, which focuses on the stories of two (now former) TJ soccer players from Central America. That project revealed that, while it can take time to adjust to the new language and culture, many students eventually find TJ to be a haven of security and camaraderie, especially for those living in small apartments packed with extended family. But whatever sense of home these students had discovered on Walnut Hill Lane was vaporized that night in October.

The Tornado and Its Aftermath

Maribel Morales, 45, a member of Iglesia Cristiana Emanuel, which sits a half-mile west of Thomas Jefferson High School on Walnut Hill Lane, is consoled by fellow church member Ashley Villalobos, 23, as she surveys severe damage to the church after an EF-3 tornado tore through Northwest Dallas on Sunday, October 20, 2019.

Jeffrey McWhorter

Juan Serrano, a TJ student who graduated in 2022, helps clear downed trees on Bowman Boulevard about a mile east of TJ the day after the tornado.

Jeffrey McWhorter

Eduardo Flores, Dennilson Duarte, and Brandon Avila, left to right, TJ students who graduated in 2020, walk through destroyed portable buildings behind Thomas Jefferson High School 10 days after the tornado. “I came here seven years ago from Honduras,” Duarte said in 2019. “Thomas Jefferson and Cary Middle School has been my home for the past seven years, and losing them feels like I’m losing my home again.”

Jeffrey McWhorter

Chairs and desks are tangled with roofing joists and insulation in the wreckage outside Cary Middle School, which sat immediately adjacent to TJ, the morning after the tornado.

Jeffrey McWhorter

Yoseline Flores, who graduated from TJ in 2022, stares out the window of Thomas A. Edison Middle Learning Center on TJ’s first morning at the temporary campus, October 23, 2019. Three days after the tornado, the entire school was relocated nine miles south to the former middle school campus, which had been used by the district for staff training and student events.

Jeffrey McWhorter

Volunteers from Pinkston High School, which sits less than a mile from Edison and whose mascot is the Vikings, welcome TJ students on their first day at the temporary West Dallas campus on October 23, 2019.

Jeffrey McWhorter

TJ principal Sandi Massey welcomes students on their first day at the temporary campus. Massey, who was recognized as Preston Hollow People’s Person of the Year for her leadership through the tornado and its aftermath, remembers both the joy and jitters of that day. “My heart leapt the more students I saw get off of buses, but I could see in their faces that they were nervous.”

Jeffrey McWhorter

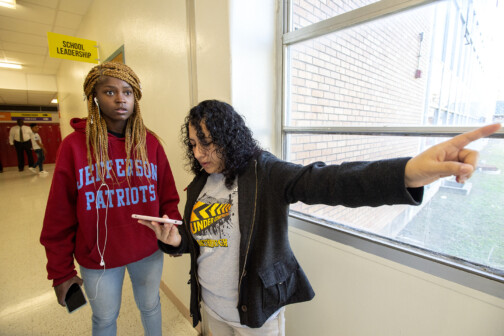

Destiny Moreland gets directions to her first class from Spanish teacher Elena Rivera on the students’ first day at Edison.

Jeffrey McWhorter

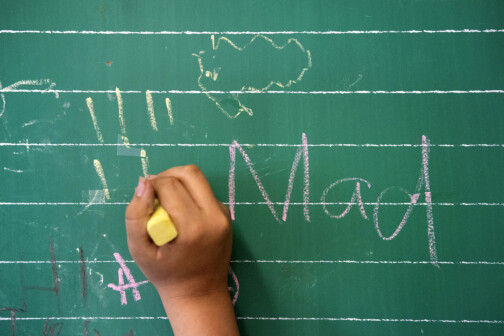

A special needs student writes “Mad” next to a picture of a storm on a chalkboard during an exercise designed to help students process their emotions during their first day at Edison three days after the tornado.

Jeffrey McWhorter

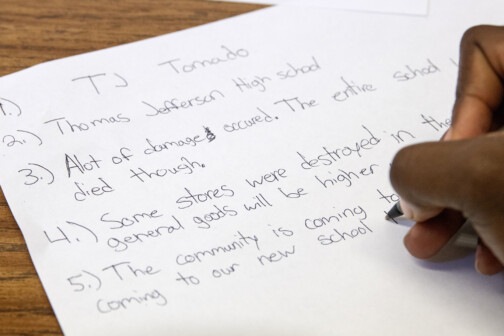

A student completes an in-class exercise about the economic impact of the tornado on the students’ first day at Edison.

Jeffrey McWhorter

TJ student Jorge Martinez, left, who graduated in 2022, helps a volunteer move donated shelving units into classrooms at Edison on November 30, 2019. Because of the age of the temporary campus, storage space was a major need after TJ moved in.

Jeffrey McWhorter

A work crew cleans up the athletic facilities at TJ on October 28, 2019. Two days before, at TJ’s homecoming football game, Dallas Cowboys owner Jerry Jones pledged $1 million to rebuild the school’s athletic facilities and football field.

Jeffrey McWhorter

The TJ football team runs onto the field for their homecoming game against H.G. Spruce six days after the tornado on October 26, 2019 at Loos Fieldhouse in Addison. The game drew a huge crowd and served as a rallying point for alumni and the broader community.

Jeffrey McWhorter

From left, Dallas Cowboys owner Jerry Jones, team executive vice president Charlotte Jones Anderson, and former Cowboy Hall of Famer Charles Haley present a check for $1 million for the rebuilding of TJ’s athletic facilities to then-Dallas ISD superintendent Michael Hinojosa and principal Sandi Massey before TJ’s homecoming football game on October 26, 2019.

Jeffrey McWhorter

Dallas ISD District 1 trustee Edwin Flores answers questions from TJ teachers, administrators and community members regarding the future of the schools affected by the tornado on December 5, 2019 at W.T. White High School in Dallas.

Jeffrey McWhorter

TJ Principal Sandi Massey asks a question during the community meeting on December 5, 2019. At the meeting, Trustee Flores announced that Cary Middle School was a total loss and would be replaced by a K-8 school, while TJ’s damaged building would be rebuilt and improved to meet “current standards.”

Jeffrey McWhorter

Eduardo Flores, front, and the TJ boys soccer team warm up before tryouts at their temporary West Dallas campus on December 5, 2019.

Jeffrey McWhorter

Oquelí Salinas, center, and other TJ students dance at their Sadie Hawkins dance on February 13, 2020 in the gym-turned-sanctuary of Northway Church, which sits across the street from TJ’s Walnut Hill campus. The church, which was also damaged by the tornado, frequently shared its facilities with TJ in the years following the tornado.

Jeffrey McWhorterMiraculously, no one died or was severely injured during the EF-3 tornado’s 32-minute tear through the heart of North Dallas. The event caused $1.55 billion in damage, making it the costliest tornado in Texas history. When the sun rose the next morning, TJ and the adjacent Cary Middle School were a twisted mess of school desks, HVAC ducting, and bricks.

The community rallied to help. Businesses, alumni, and churches poured in so many supplies—paper, pens, highlighters, snacks, coffee supplies, Post-It notes—that former principal Sandi Massey said she felt like she was “running a nonprofit” on top of her normal duties. Even Cowboys owner Jerry Jones joined NFL Hall of Famer and TJ neighbor Charles Haley at the homecoming football game that weekend to present a $1 million check to help fix TJ’s mangled field. Through the Herculean effort of faculty and staff, the entire student body was reunited just three days later at Thomas A. Edison Middle Learning Center, an old West Dallas middle school that was being used for Dallas ISD staff training and student activities. It is 9 miles south of the battered campus, a 45-minute bus ride from home.

While the TJ community was grateful to not be scattered to other campuses like neighboring Cary Middle School had been, their temporary digs were small and aging. Senior Jacky Badillo remembers the crowded hallways surging with bewildered students on that first day. Current senior class president Noe Murillo worried about meeting the rats he had heard roamed the halls. (He never did.)

“A lot of us had to dig down deep and say, ‘We can do this, we’ve got this, we’re gonna do whatever it takes,’” says longtime office manager Marilyn Jordan. For weeks following the tornado, former principal Massey says she would hold her emotions in check all day and then get in her car and “cry the whole way home.”

But the world spun on as it does after every natural disaster. The streets were cleared of snapped telephone poles and crushed cars. Homeowners boarded windows and dug in for long insurance battles. Weeds grew high in the TJ courtyard, and the kids down at Edison settled into a new sense of normal.

For about four months.

Another Displacement

Principal Sandi Massey opens the front doors of Edison at 6 a.m. on December 17, 2020. Not five months after the tornado, TJ was displaced yet again by the COVID-19 pandemic. “You start hearing what’s happening in China on the news,” Massey said, “and by spring break we’re all handing out computers and laptops for students to go home and stay online the rest of the year.”

Jeffrey McWhorter

Thomas Jefferson football coach Ryan Burchfield and cross-country coach Rebecca DeLuna move supplies to Burchfield’s truck as the school prepares to transition to online learning amid the COVID-19 outbreak on March 13, 2020.

Jeffrey McWhorter

Parents wait in line for a Dallas ISD drive-thru food pickup on March 30, 2020 at Medrano Middle School in Northwest Dallas. As Dallas ISD transitioned to virtual learning for all students that spring, district employees scrambled to deliver both food and technology supplies, such as laptops and hotspots, to families.

Jeffrey McWhorter

Jorge Martinez, who graduated from TJ in 2022, attends class virtually from his family’s Northwest Dallas apartment while his younger brother, Junior, sneaks a peek on December 17, 2020. “I didn’t really have a high school experience,” said Martinez, who is now a freshman at Babson College near Boston.

Jeffrey McWhorter

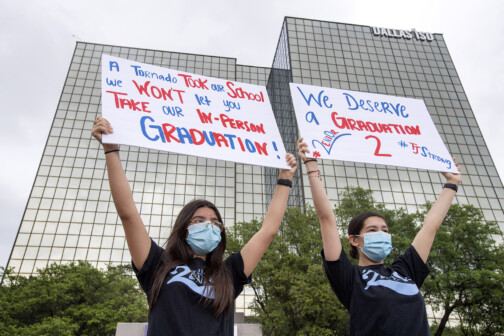

Juli Amaya, 17, left, and Katherine Gil, who graduated from TJ in 2020, hold signs protesting Dallas ISD’s decision to not hold in-person graduation ceremonies due to the coronavirus pandemic on May 13, 2020. The two were part of a protest outside the Linus D. Wright Dallas ISD Administration Building.

Jeffrey McWhorter

After Dallas ISD moved all in-person graduation ceremonies to virtual, senior class sponsors planned a drive-thru “senior sunset” at which students paraded their decorated cars around the tornado-damaged campus on May 19, 2020.

Jeffrey McWhorter

Thomas Jefferson High School seniors practice social distancing as they line up in the parking lot of their tornado-damaged school to get their photos taken for a virtual graduation ceremony during the “senior sunset” on May 19, 2020.

Jeffrey McWhorter

Nearly seven months after the tornado, TJ’s Walnut Hill campus sits deserted and overgrown on May 15, 2020.

Jeffrey McWhorter

A lone student wears a mask as she stands in a beam of light in the Edison gym on December 19, 2020. By mid-fall TJ’s enrollment had dropped by nearly 350 from its pre-tornado numbers and only about a quarter of TJ’s 1,600 students were showing up consistently for in-person classes. “That might be the most difficult year I’ve ever had as an educator,” said principal Massey.

Jeffrey McWhorter

A purple-grey mist hangs over Bachman Lake on a 57-degree morning as the TJ cross country team gathers for their first official in-person practice of the season on September 10, 2020. With masks and social distancing strictly enforced, they ran the 5K loop in preparation for their first meet, then headed back home for another day of online learning.

Jeffrey McWhorter

The Thomas Jefferson varsity football team poses for a group portrait on November 13, 2020 on the practice field behind Edison. After missing two weeks due to COVID-19, and with several students not eligible because of failing grades, the football team had only nine players out for practice a week before their homecoming game, which was ultimately canceled. “It makes me sad some to feel like they didn’t get to have the experience that I hoped that they would have,” says former defensive backs coach Ryan Burchfield, “but also just super proud of those kids because they never complained.”

Jeffrey McWhorter

A student sits in a classroom with desks blocked off for social distancing on the first day students could return for in-person learning on October 8, 2020 at Edison.

Jeffrey McWhorter

TJ biology teacher Megan Lyons teaches virtually on the first day students were able to return for in-person learning on October 8, 2020 at Edison. Assistant principal Erika Vigil remembers encouraging her Zoom-fatigued young teachers to not quit. “It’s because you’re here for kids and you don’t get to see them every day,” she’d remind them. “You saw black boxes.”

Jeffrey McWhorter

Jairo Guardado, who graduated in 2021, participates virtually into his anatomy class while working in the stock room of Shoe Palace on December 17, 2020 in Northwest Dallas. “The good thing is it’s slow today,” Jairo said. “If it was busy, there was no way I could have done work.” Jairo was saving money to buy a car. He offered to help pay medical bills for his grandmother, who had breast cancer, but she refused to take it.

Jeffrey McWhorter

Jorge Martinez reads a bedtime story to his three younger siblings on December 14, 2020 in his family’s apartment near Bachman Lake. While Jorge kept up with his virtual schoolwork, he would also help his siblings with their own and make dinner in the evenings when his mom and stepdad had to work. “I would have liked that; it would have been different,” Jorge said of his high school experience. “But I’m glad that it happened because I feel it took courage.”

Jeffrey McWhorter

Jordi Miranda, who graduated from TJ in 2021, works at the Morton H. Meyerson Symphony Center, cleaning seats as part of their COVID-19 protocol, on December 23, 2020.

Jeffrey McWhorter

TJ assistant principal Paige Zumberge and social studies teacher Gretta Kershner deliver an award of appreciation to Alan Longoria for demonstrating perseverance throughout the pandemic on February 10, 2021. Massey described attendance that year as a “constant battle,” and members of her team would fan out into the community each week to “lovingly harass” the missing students, encouraging them to check in with even a text to their teachers.

Jeffrey McWhorter

TJ teachers Ryan Burchfield, left, and Peter Buhler deliver a certificate of appreciation at the home of a student who had shown perseverance and tenacity throughout the pandemic on February 10, 2021.

Jeffrey McWhorter

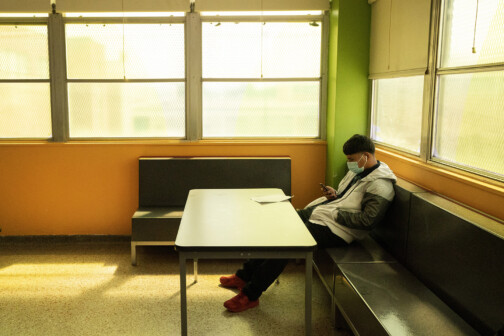

As a bitter legal battle wore on over Dallas ISD’s ability to mandate face masks, TJ students arrived at Edison for their first day of fully in-person classes in a year on August 16, 2021. A mask-wearing student sits alone in the corner of the cafeteria.

Jeffrey McWhorter

World history teacher Megan McCleskey peers over the construction fence around TJ’s Walnut Hill campus before a community outreach event on February 10, 2021. The rebuild effort was slowed by controversy in the summer of 2020 when the original construction contract was canceled after a Dallas ISD board member presented allegations of corruption. Throughout the spring of 2021, the campus still sat largely untouched.

Jeffrey McWhorterLike every other school in the nation, TJ stumbled through the spring of 2020, doing drive-thru everything, navigating ever-shifting CDC guidelines, and making the best of an impossible situation. Once again, students looked into adult faces just as bewildered as their own and heard a familiar refrain: “Be patient. Be flexible. We’ll figure this out as we go.”

“At that point, I feel like that year was thrown out the window,” says Murillo, the senior class president.

But to assistant principal Erika Vigil, COVID was also a blessing in disguise. “The pandemic actually, I think, saved TJ,” she says. “It gave people and teachers the emotional and mental break. For a lot of our veteran [teachers], it was like, ‘I can breathe.’”

However, the next fall brought a low point in morale. As many better-resourced private and suburban schools (which hadn’t been hit by a tornado) saw a near full return to in-person learning, albeit behind plexiglass and facemasks, the hallways of Edison were ghostly. By December, enrollment had dropped by nearly 350 and only about a quarter of TJ’s 1,600 students were showing up for in-person classes. In November, when the football team should have been preparing for its homecoming game, nine boys dressed for practice. The rest of the season was canceled.

“That might be the most difficult year I’ve ever had as an educator,” Massey says. Vigil tried her best to encourage Zoom-fatigued, young teachers on the brink of quitting. “It’s because you’re here for kids and you don’t get to see them every day,” she’d remind them. “You saw black boxes.”

Everyone agrees the geographic displacement compounded the problem, especially for a community heavily reliant on public transportation. “No kid wants to be on a bus by themselves for 45 minutes, to then come into a classroom to do nothing,” Vigil says.

“It gave them almost an excuse to stay away from the building, that they had to travel to get to West Dallas,” Massey says.

With absences piling up, TJ staff fanned out into the community each Wednesday to “lovingly harass,” as Massey put it, their invisible students while encouraging those who had stayed the course. They found that many students had taken daytime jobs or picked up extra hours to help families struggling financially during the pandemic.

Jairo Guardado virtually checked into his anatomy class as he restocked shelves in the back of the Shoe Palace on Webb Chapel. Badillo, whose mother’s housecleaning work had been significantly cut by the pandemic, took a job at Sunset Crab Shack in Pleasant Grove to help with rent. “I had to sometimes skip classes to go to work because I was scheduled in the morning,” she told me. “I lost a lot of credit that semester.”

By the end of that long and trying year, the tornado and the normal life it disrupted felt like a distant dream. After eight years at the helm of TJ—the longest tenure of any Dallas ISD principal at the time—Massey, who had been named Preston Hollow People’s Person of the Year for her leadership, took a new job in Colorado. She was replaced that summer by a young, charismatic, first-time principal named Ben Jones who came from across town at Bryan Adams.

The rebuild effort had been slowed by controversy the previous summer when the original construction contract was canceled after a Dallas ISD board member brought allegations of corruption. But by the time Jones greeted his first busload of students at Edison, in August 2021, a new contractor, Beck, had been hired, and dirt had finally begun to move.

Although total enrollment remained low after COVID, students began to hesitantly refill the hallways as the new administration sought to narrow the academic and social-emotional gaps left by the pandemic. A light of hope and optimism slowly dawned as shiny new facilities took shape back on Walnut Hill. That light was dimmed on May 5, 2022, when 17-year-old Jorge Hernandez, a TJ senior just two weeks from graduating, was shot and killed as he sat in the front seat of his friend’s 2007 Escalade. It was a reminder that, as principal Jones put it, “moving back in to 4001 Walnut Hill is not going to solve all of the problems.”

Rising Light

The Dallas skyline rises in the distance as students disembark buses in front of Edison for their first day of fully in-person classes in more than a year on August 16, 2021.

Jeffrey McWhorter

New principal Ben Jones makes an announcement over the public address system on his first day at the helm of TJ on August 16, 2021. After leading TJ for eight years, Massey took a job in Colorado and was replaced by Jones, a young, first-time principal who had previously been an assistant principal at Bryan Adams High School. “There’s no secret that when I was hired, a big part of the charge was: take care of the trauma, take care of people, but get us back on track academically. That’s been, I think, a hard balance to strike,” Jones said.

Jeffrey McWhorter

TJ alum Roberto Garcia, who now teaches newcomers in TJ’s Dallas International Academy, looks out the window as students board buses outside Edison on September 23, 2022. Garcia, who was born in Mexico and brought to the U.S. as a child, understands the mentality of his immigrant students. “That’s the most resilient group of humans I’ve ever met,” Garcia said. “I mean, their stories make the tornado of 2019 seem like a fairy tale compared to what they’ve lived.”

Jeffrey McWhorter

A curb is demolished in front of TJ along Walnut Hill Lane on November 17, 2021. After the original construction contract was canceled, the district hired The Beck Group, and dirt began to move in the summer of 2021.

Jeffrey McWhorter

Construction workers move materials into Walnut Hill International Leadership Academy, a pre-K through 8th grade school that replaced the destroyed Cary Middle School, on Aug. 27, 2022.

Jeffrey McWhorter

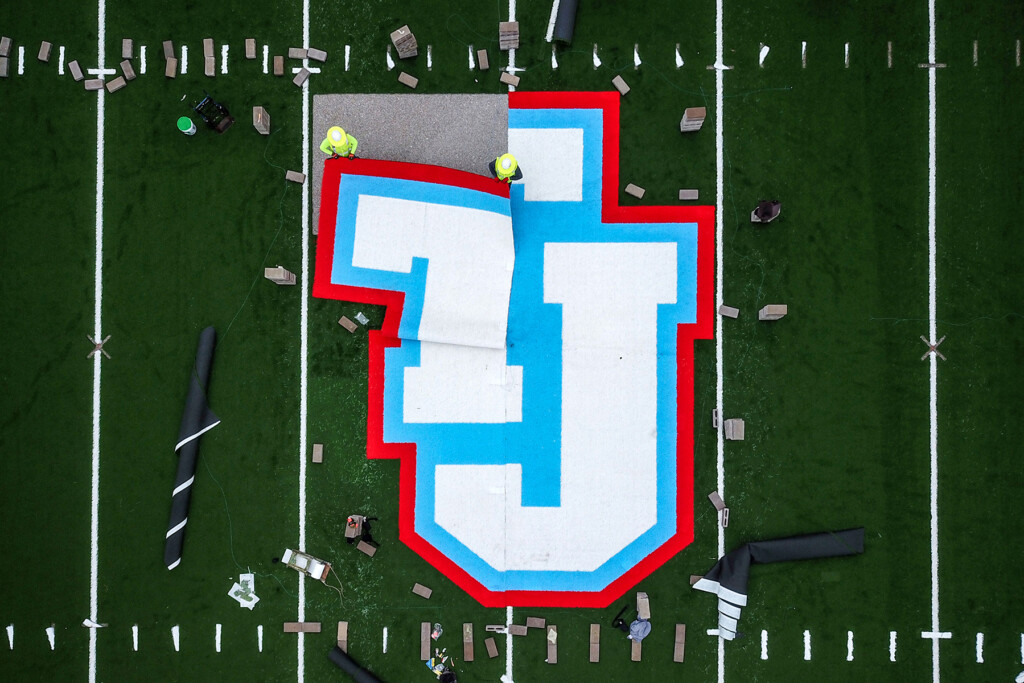

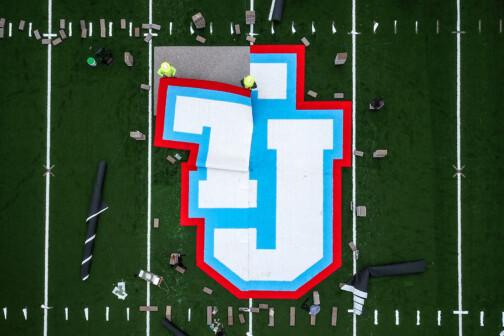

Workers install the TJ logo in the center of the school’s new turf practice field on May 23, 2022. The $1 million pledged by Cowboys owner Jerry Jones helped pay for the new field.

Jeffrey McWhorter

Friends and family gather for the interment of Jorge Hernandez, a 17-year-old TJ senior, on May 13, 2022 at Crown Hill Memorial Park Cemetery in the Bachman Lake neighborhood. Hernandez was shot and killed while in a car with three other young men on May 5, 2022.

Jeffrey McWhorter

Jorge Hernandez’s mother, Silvia Lujan, raises her son’s graduation cap and asks for a round of applause in recognition of his achievement moments before his casket is closed. Hernandez, who struggled academically, had recently improved his grades and qualified for graduation just days before his death.

Jeffrey McWhorter

Varsity boys soccer players hang out in the bed of a pickup truck in the parking lot of Northway Church before a team dinner hosted by the church on March 3, 2022. The under-construction Walnut Hill International Leadership Academy and Thomas Jefferson High School can be seen in the background.

Jeffrey McWhorter

TJ alum-turned-teacher Roberto Garcia, right, watches a World Cup match between Mexico and Saudi Arabia with his third period World Geography class on November 30, 2022 at Edison.

Jeffrey McWhorter

TJ students descend a stairwell on their final first day of school at Edison on Monday, August 15, 2022.

Jeffrey McWhorterFolks around TJ still have a hard time containing their excitement about the new building. Badillo, who plays soccer and runs cross country, cannot wait to check out the state-of-the-art training room. Principal Jones boasts of a culinary kitchen that “some restaurants in this city would be jealous of.” And soccer coach Mark Wolveck marvels at the flawless, colorful turf that replaced the “potato field” his team used to practice on.

But January’s homecoming is about more than smart boards and matching furniture. It’s about a community accustomed to life in the shadows finally getting its day in the sun.

Office manager Marilyn Jordan, who lives near the Bachman Lake community, reflects on the students she loves: “It’s almost as if they’re used to being—I don’t like to use this word, but I’m going to—unworthy of getting goodness in life. … I want them to feel that they deserve it, because they certainly do.”

Ben Jones saw the same thing in the eyes of his teachers when they toured the campus for the first time in December. “There was this feeling of ‘Oh, we can have nice things! We get nice things.’ Because even before the tornado, there was this kind of sense of ‘We just don’t do that. We don’t do the nice things.’”

It had been 1,188 days since the tornado when the TJ students walked through the doors of their rebuilt school on January 9.

Of the nearly 1,900 students enrolled then, only about 235 remain at TJ. They were just two months into their freshman year when the twister hit. They were full of optimism and ambition, looking forward to proms and homecomings, chess tournaments and class trips. Instead, they got three years in an old middle school with a year-long interlude staring at glowing rectangles in their bedrooms and workplaces. There is no denying the sadness over what was lost.

“I didn’t really have a high school experience,” says Jorge Martinez, who graduated last year.

And while they generally share an enthusiasm for the return, some seniors carry trepidation about yet another change at the end of a high school journey marked by upheaval. Geovani Roman says he’d finally gotten used to life at Edison. Changing campuses again in his last semester feels almost “like the tornado happening again.”

But regardless of the emotions they may feel upon returning, these surviving seniors represent a head-down, grind-it-out ethos that is deeply ingrained in the Latino immigrant community of Northwest Dallas. Their parents are the dishwashers, housekeepers, and construction workers who keep this city running, and they’ve passed a steely-eyed determination to their children.

“We grow up seeing our parents go to work at 5 in the morning, come back at midnight, and I want to say that the vast majority of these kids adopt that mindset,” says Roberto Garcia, a TJ alum-turned-teacher who was brought to the United States from Mexico as a child. “It’s that immigrant mindset that got them through these last three years and finally to a place where they can enjoy something nice for a while instead of pretending that everything’s okay.”

Massey, the former principal, reflected on those students during a Zoom interview last month. She paused, then buried her face in her hands and wept. “These are the best kids in the world.”

Home Again

World history teacher Megan McCleskey jokes with her daughter Jackie Hake, a 17-year-old TJ senior, as they move a laminator down the hall on January 4, 2023.

Jeffrey McWhorter

Haleigh Thompson, an ESL teacher in the Dallas International Academy, arranges desks in her new classroom in the renovated building during a teacher work day on January 4, 2023.

Jeffrey McWhorter

The varsity girls basketball team practices in the renovated gymnasium on January 5, 2023.

Jeffrey McWhorter

Joaquin Gonzaga gives his parents, Alina Aguayo and Andres Bejar, a thumbs up before walking into the renovated building on the students’ first day back, January 9, 2023.

Jeffrey McWhorter

Arlette Rayo and Juan Mendoza hang out together on the “learning stairs,” a showcase feature of the renovated building, during their first day back on campus.

Jeffrey McWhorter

A student walks past a sign giving directions to the gymnasium, which serves as a tornado shelter, on the students’ first day back. The signs are noticeably ubiquitous around the rebuilt campus.

Jeffrey McWhorter

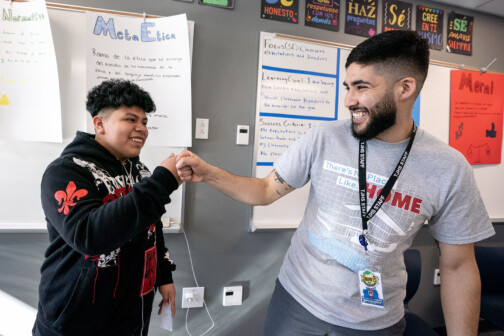

Spanish teacher Roberto Garcia gives Brayan Alvarez a fist bump during class on the students’ first day back.

Jeffrey McWhorter