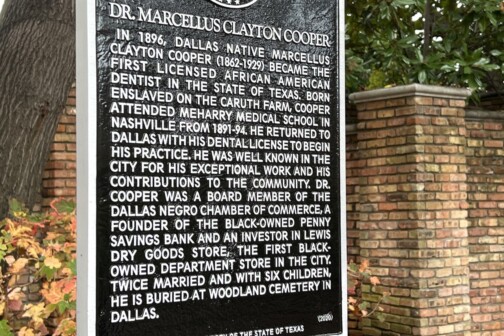

Wednesday morning, dozens of people gathered at Communities Foundation of Texas to watch the dedication of a historical marker honoring Dr. Marcellus Cooper, the first Black dentist in Texas. But the day was also poignant because the man who had a hand in making sure Cooper got his due wasn’t there.

George Keaton Jr., considered the foremost historian of Black Dallas’ past, had died the night before at Baylor University Medical Center after a brief battle with cancer. He was 66.

It’s difficult to find someone who hasn’t benefited from Keaton’s insatiable thirst for knowledge about Black Dallas. Anyone who has taken one of his bus tours, attended a historical marker dedication that he had advocated for, or simply followed his work with the organization he founded, Remembering Black Dallas, can probably point to an instance where Keaton exposed a piece of history they were unaware of.

In 2019, he told Dallas Doing Good that his interest in Dallas history started with investigating his own family history during his time at North Texas State University, which is now the University of North Texas.

After graduating, he earned a master’s in clinical counseling and a degree in guidance counseling. He worked for Dallas ISD for 31 years before retiring, first as an elementary school teacher, then as a guidance counselor. He formed Remembering Black Dallas after a long membership with Dr. Mamie L. McKnight’s organization with a similar mission, Black Dallas Remembered.

“We started about four years ago out of what I felt was a need,” he said. “There was a void. By the time I retired, Dr. Mamie McKnight had not been able to continue her organization for about the last 10 years.”

His work has helped preserve the stories of those who came before and helped the city recognize history that was fading from public view.

“He voiced yesterday that he thought that he would have more time because he still had so much to do,” the organization said in a Facebook post announcing his death.

Jerry Hawkins, a member of the Dallas County Historical Commission and the executive director of the nonprofit Dallas Truth, Racial Healing & Transformation, echoed that statement.

“He had so much more to do. He was only 66, that’s very young,” Hawkins said. “He was not ready to die. There were things he was still working on uncovering. He was getting some stability in his organization. He was going to lead a Green Book tour. I recently talked to him, and he didn’t talk about dying. He was not prepared to go, which is sad. I’ve been feeling the weight of it a lot. He was just not ready.”

Hawkins and others who worked with him point to his body of work as a lasting legacy. Even recently, Keaton had pushed for a marker noting the lynching death of Allen Brooks, whose body was hanged at Main and Akard streets in 1910. Keaton also convinced the city to clean up and install a public memorial to the victims of the 1860 lynchings at Martyrs Park downtown, near Dealey Plaza.

“He was leading the effort along with other folks from Remembering Black Dallas,” Hawkins said of Keaton’s work on the markers, which the historical society was responsible for reviewing. “They submitted the most applications for historical markers, particularly for Black folks who have been left out of the historical record in Dallas. Most of the ones we approved at every meeting were ones that Remembering Black Dallas and George Keaton submitted. And he also held webinar sessions so other folks could know how to apply for them and research them.”

Dallas civil rights leader Rev. Peter Johnson says that Keaton was a “pure historian.”

“He understood the relationship between yesterday and today, and as a serious, sensitive observer of history, he had a clear understanding of how we got here,” Johnson said. “ He was very sensitive to making sure that this part of the world did not forget its history and the people who played important, significant roles in shaping what Dallas is today.

“You can’t have Dallas history without Black history and you can’t have Black history in Dallas without Dallas history. It is all tied together.”

In one of his last interviews before his death, Keaton explained his desire to show people what he called the “hidden history of Dallas.”

“I think it’s most rewarding when we see people discover and learn about the place where they live,” he said, after acknowledging that the city’s history of segregation—and its segregated present—often meant Dallas’ Black history is “hidden in plain sight.”

Hawkins said that Keaton’s work was vital and hardly ancient history. On Wednesday, he pointed out that one of Marcellus Cooper’s grandsons spoke at the dedication ceremony. “We heard from a grandson of somebody who was enslaved,” he said. “We’re not that far removed from this—a living descendant of an enslaved person was there, talking to us. This is recent history.”

The fact that Dallas’ past is still impacting its present—Hawkins pointed to studies regarding present-day health, infrastructure, and economic inequity in historically Black neighborhoods—sometimes made some people frustrated with Keaton’s stances.

“Dr. Keaton was a teacher of history, and folks like me wanted him to be more demanding, if that makes sense,” Hawkins said. “His family was enslaved on the Caruth plantation—they were the largest landowners in Dallas, and in my opinion, and the facts support it, they owe his family something. He really didn’t talk like that. He just wanted the acknowledgment.

The Caruth plantation grew to over 11,000 acres, stretching the modern day Communities Foundation at Caruth Haven Lane to south of SMU.

“And you know, that was very admirable of him because he did the teaching and was willing to volunteer his time to help people learn these things, but that’s not justice,” he said. “Justice is when your family can also benefit from the things that you all did for free.”

But even with their differences over how history should be recognized, Hawkins said he respected and admired Keaton. “I had a deep appreciation for him, spent a lot of time with him, learned a lot from him, and was just amazed at all the things that he was able to do and accomplish,” he said. “He always picked up the phone for me.”

Johnson said that Keaton’s patient way of explaining this history didn’t mean that people were always comfortable hearing it.

“For White Southerners, the history is embarrassing and difficult,” he said. “For Black Southerners—and this is not just Dallas, but throughout the southern states—the history is something we prefer not to talk about. That’s what I think made George so unique—he was comfortable really forcing people to take a look at yesterday.”

Hawkins pondered Wednesday on the void that Keaton’s death would leave.

“I don’t think he was prepared for this transition,” he said. “So there was no kind of succession plan. No turning over of archives. He has a lot of things that he collected. It’s a serious situation, not just because he passed, but what is going to happen with the legacy of his work?”

Johnson, however, said he sees a new crop of future historians coming into their own in an age when technology has made it easier to do research and ask questions. Most of them found Keaton and his work.

“I trust this generation of young people to be inquisitive and to want to know—both Black and White kids,” he said. “I trust that the challenges of society will produce the next generation of thinkers and the people who will ask questions and want to take a look backward to understand us today. There will be other George Keatons coming.”

Johnson said he would like to see Keaton’s legacy marked in some tangible way—perhaps by having a Dallas ISD school named after him, a university chair in his name, or even a research area of the Dallas Public Library. But if the city was really interested in honoring Keaton’s legacy, he said, they’d be ready to continue learning about Dallas’ history, even if it makes people uncomfortable.

“George’s commitment to exposing yesterday made a number of people—both Black and White—uncomfortable,” he said. “So to me, his legacy is that he had the audacity to make us uncomfortable and to face up to Dallas’ history.”

Services for Keaton will be held on Saturday at Christian Chapel Temple of Faith, at 14120 Noel Road. An informal viewing will be held on Friday from 1 p.m. to 7 p.m. at the Evergreen memorial Funeral Home, and his body will lie in state at the Hall of State at Fair Park on Thursday.

Get the D Brief Newsletter

Author