Editor’s Note: The Dallas City Council unanimously approved the WOCAP plan during Wednesday’s agenda meeting.

Last March, construction workers put up a fence along both sides of 8th Street near Bishop Arts, blocking off about a dozen old two-story apartment buildings and duplexes. The developer Lennar Multifamily Group bought these properties from the McDonald family, who had owned the affordable units for decades. When they were sold, the most expensive rented for $1,200.

Lennar is doing what the city’s zoning allows it to do: demolishing those 65 units and replacing them with 252 market-rate apartments of between 500 and 1,400 square feet. The apartment buildings will be four stories tall and extend down both sides of 8th from Adams to Llewellyn, sparing only a house that Lennar didn’t scoop up. Those plans are in line with the new development that now flanks Bishop Arts.

Over the past few months, Councilman Chad West and his plan commissioner, Amanda Popken, have mentioned the changes to 8th Street as a reason why neighborhoods further south need an area plan that will help shape what can and can’t be built. In 2019, the city changed how it modifies neighborhood zoning by implementing a point system that ranks priority communities. An area plan is a good way to jump to the top of the list.

North Oak Cliff went through its own rezoning process a dozen years ago, encouraging density like what Lennar is bringing to 8th Street. The apartments up and down Zang Boulevard along the streetcar route were born from that rezoning, too.

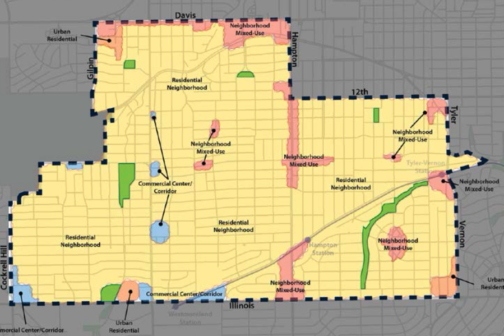

Further south is a different matter. The West Oak Cliff Area Plan, which goes before the full City Council for a vote this afternoon nearly three years after the process began, will set the table for how five neighborhoods west of Tyler Street will eventually be rezoned. Those include downtown Elmwood; the area around the North Cliff Neighborhood Center, at Pierce and Catherine streets; Edgefield and Clarendon, near Winnetka Elementary; Hampton and Clarendon, down to Illinois; and a portion of the Jimtown neighborhood, which is packed in below Clarendon just west of Hampton.

If the plan is approved, it will help trigger what’s known as an authorized hearing. That’s the process by which the city considers rezoning a neighborhood.

Here’s the tall goal from the plan itself: “Due to the three DART light rail stations in and around the area, as well as the ongoing and continued growth in the Bishop Arts District to the northeast, this area is one where there are concerns about potential future growth pressures and subsequent fears of gentrification and displacement.”

Its aims is to protect existing single-family neighborhoods, encouraging softer, “missing-middle” density like accessory dwelling units, duplexes, and triplexes. The plan urges the city to preserve natural areas and expand trails. It highlights communities that don’t have sidewalks and where other infrastructure is lacking. It finds potential for development in old buildings. It rethinks downtown Elmwood, which is home to small storefronts, restaurants, auto shops, and convenience stores—and a way-too-wide Edgefield Avenue, which features no means of traffic calming, as well as missing sidewalks.

The only significant proposed density is around DART’s Hampton Station, which is one of six park-and-rides that the city is seeking to develop.

“I think there is a groundswell of support in protecting these neighborhoods and listening and standing up for people who haven’t been at the table for decades,” Popken says.

But the plan hasn’t been without its challenges, mostly involving communication with the people Popken mentions. Many of the early discussions around WOCAP, as it is abbreviated, happened during the pandemic. Early listening sessions were only in English and documentation wasn’t bilingual. (In the study area, 86 percent of the nearly 44,000 residents identifies as Latino.) The city’s first take advised making automotive businesses—a significant industry in this part of Oak Cliff—a non-conforming use. Some of the proposed density—duplexes, triplexes, and the like—made some neighbors nervous. They maybe didn’t understand what the city was proposing, and the city must do a better job of educating and outreach. (I met a South Edgefield resident after dinner at Elmwood Farms who told me that he thought WOCAP meant the city would be turning his block into apartments because someone told him that. He said he had no contact with anyone from the city.)

Those challenges, though, led to organizing efforts throughout the community. The West Oak Cliff Coalition worked to align the voices of many of these neighborhoods and, yes, the auto shops. Somos Tejas, activists who help organize Latino neighborhoods, knocked on hundreds of doors. The Automotive Association of Oak Cliff helped push back, and the version of WOCAP approved by the City Plan Commission has removed the language supporting making auto businesses non-conforming. At least two new neighborhood associations formed and a dormant one was revived. All of that is due to community organizing.

“We engaged hundreds of people,” says Yolanda Alameda, a former president of the Polk/Vernon Neighborhood Association who helped organize through the West Oak Cliff Coalition. “We have lots of next steps and we’ll help work with neighborhoods that are eager to start associations.”

The South Edgefield neighborhood, just north of Tyler Station and the adjacent DART light rail, was one of the communities whose organizing brought changes to the plan. It was successful in convincing the city to suggest allowing only ADUs for their half-mile community. The plan cites “significant opposition to Missing Middle Housing.”

But there is nuance in the plan’s language, too: “There was also some expressed support for further community engagement and review through the authorized hearing process to allow for other missing middle housing types, specifically duplexes, triplexes, quadplexes, and cottage home developments on larger lots.”

That indicates an opportunity for additional housing units in an in-demand neighborhood, which helps regulate housing prices by increasing supply.

“There’s more information that needs to be shared with the neighborhoods,” Alameda says. “They need to have a greater understanding of all the options, all the potential and the ramifications of (missing middle). In the absence of that information, what they felt most comfortable with was some very limited increased density.”

Much of the study area shows what the city has long ignored. South Edgefield is a perfect example: despite being within view of the DART line, there are entire blocks without sidewalks. Go a block or two south into Elmwood near the mixed-use Tyler Station, and it’s a different story. There’s even a wide path that stretches about a half-mile to the nearby Elmwood Parkway park.

In fact, in 2018, D Magazine highlighted two areas that were ready for properly managed redevelopment. Both are included in WOCAP. They are Pierce and Catherine and Edgefield and Clarendon, both home to small buildings from generations ago that could be the nexus of their neighborhoods.

“This neighborhood was built in 1920s when everything needed to be walkable, so it was zoned commercial on street corners,” Popken says. “That is really hard to come by because we haven’t been building this in 80 years.”

Councilman West has used the example of the teardown of El Corazon in North Oak Cliff as the impetus for moving WOCAP forward. The beloved Tex-Mex restaurant was replaced with a CVS and an ocean of parking because the neighborhood wasn’t proactive in defining its future.

“This is but one example of many in our city where the lack of good planning resulted in someone outside the city—here, a national drug store chain—making decisions for us that we’re now forced to live with for decades,” West says. “The West Oak Cliff Area Plan is our chance as a community to plan for the future.”

Full disclosure: I live in Elmwood, and I was present for a few sometimes-tense sessions during living room neighborhood meetings. The Council is now voting on a plan that has support from the community organizers that pushed to change the recommendations around auto shops and density. Development will come to this part of Oak Cliff, and West believes the way to slow its impact on the many working people who live here will be to set parameters that dictate what can be built and where.

The Hampton DART station, for example, is a sea of unused parking spots—adjacent to a major thoroughfare, ripe for apartments and a mix of uses. The recommendation here is four stories tall. West and the city believe that such large development isn’t fit for the single-family neighborhoods that make up most of the plan. But missing middle housing can be, especially if the city dictates design standards that allow the duplexes and triplexes to resemble what it is next to. Alameda says her neighborhood supports that sort of density. The recommendation for the rest of the WOCAP study area are buildings that are no higher than three stories.

WOCAP intends to prevent what happened further north on 8th Street, where an entire block of affordable housing was wiped out. The city’s job now will be to educate and listen.

But the reality is that the primary way to control the price of housing is to build more of it, particularly in highly desirable neighborhoods. WOCAP does that through encouraging missing middle, fitting it into what is now majority single-family. And if the plan helps create pockets of new investment and development in areas like downtown Elmwood, that desirability will only increase. The challenge will be an opportunity for the city: improving the neighborhood without pushing out the residents who have lived here for generations.

Author