The Morney-Berry Farm, located about 20 miles south of Dallas, is quiet now. That wasn’t always the case. Its patriarch, James Morney, bought the land in 1876. He and his descendants worked it hard for four generations. Though they operated just a few steps ahead of survival, the Morneys were duty-bound as a family to hold on to the land. They turned the inhospitable, craggy acreage into a thriving spread of pecan and cedar trees, harvesting hay and corn crops.

Driving up the long dirt road to the farm, you no longer see miles of hay fields or pecan tree orchards. But you will see cows and horses and some replicas of one-room quarters that housed the formerly enslaved people who first worked the land. There is a main house. The original smokehouse. Two pavilions.

It was James’ great-great granddaughter, Murdine Berry, who wanted to document the family’s history in this way. But the land came first. When some local land grabbers tried to claim parcels of the farm, Murdine fought back with litigation that went all the way to the Texas Supreme Court. It took 10 years. In 1990, the court ruled in her favor, ensuring the land would stay in the family.

As of June 24, a different Texas Supreme Court ruling could wipe the farm out of existence.

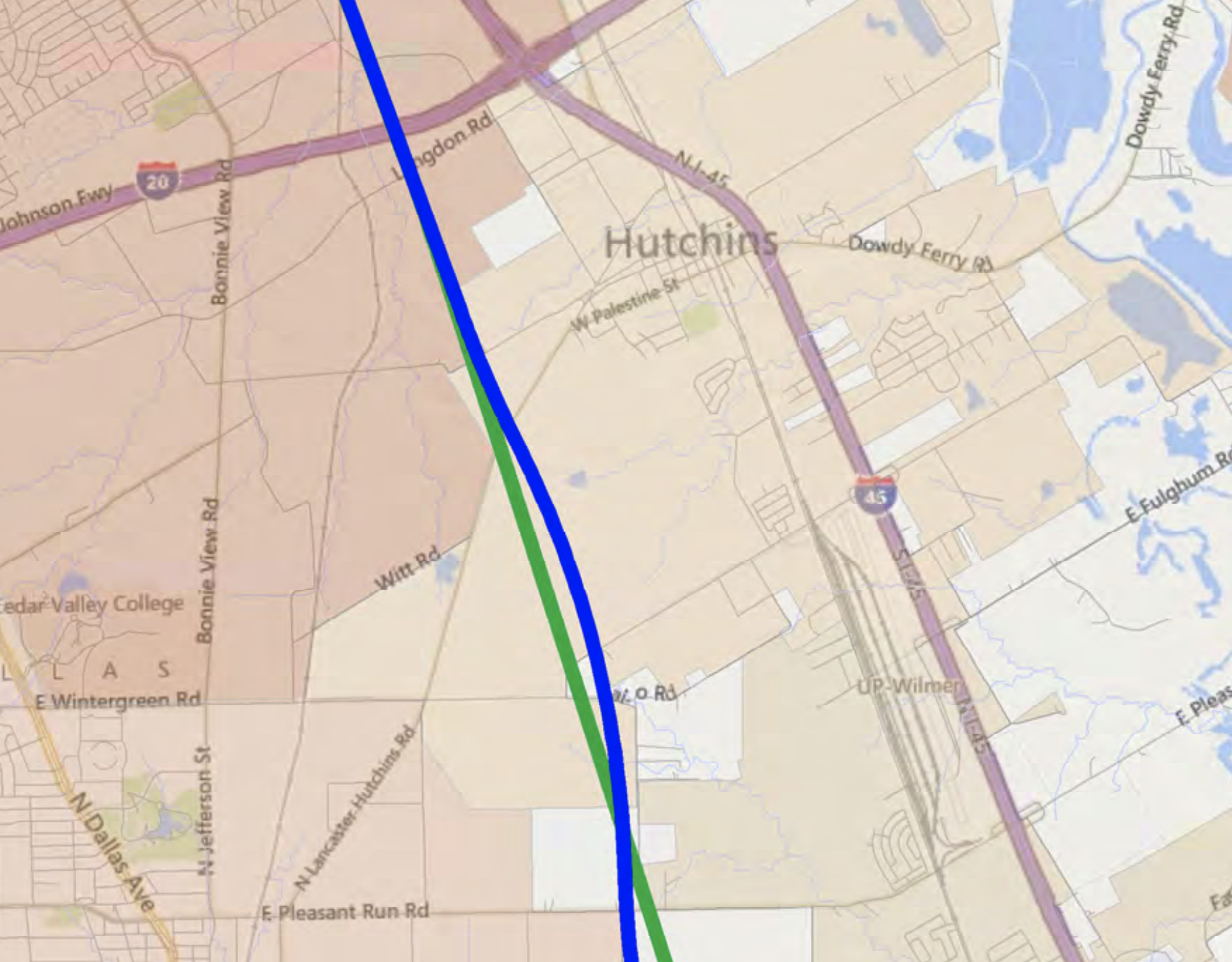

The stretch of Dallas that holds the farm is part of a federally approved route of the Texas Central Railroad’s bullet train between Dallas and Houston. The company has been in disarray. Its CEO, Carlos Aguilar, resigned in June. The board of directors has disbanded. It’s now being managed by Houston-based FTI Consultants, a company known for restructuring other companies that are facing some sort of crisis. The project at FTI is run by a man named Michael Bui, who could not be reached for comment.

Despite Texas Central’s damaged status, the court’s ruling has armed the company with the ultimate hammer: eminent domain.

Uncle Curly Dee Morney passed on the farm to Murdine. Before his death, he picked up a fistful of dirt and ceremoniously poured it into her slender hand with a single resounding command: “Do not lose the land.”

These days those words weigh heavily on Murdine’s children – Dr. Leonard Berry Jr., Linda Berry Henderson, and Jody Berry – because now, five years since Murdine passed, a bullet train appears to be routed right through the main house on their land.

After Emancipation, land ownership for formerly enslaved people meant freedom. It meant you might not have to sharecrop for an unscrupulous former owner. It meant you might not have to spend your life dodging White mercenaries looking to arrest you for “vagrancy,” then forcing you to work off your sentence by laboring on their land.

In Texas, after the Civil War, against all odds, hundreds of Black families found ways to acquire land. Granted, it was mostly in floodplains, river bottoms, and random acreage outside of county lines. But by 1890 some 26 percent of Black Texans owned land. At that point, more than 1 million Black Americans owned farmland.

Land was freedom.

But that freedom was hard to hold. By 1992, only 18,000 Black farmers owned land. Eminent domain, flooding, and unwieldy dirt were hard foes. Now, the Morney-Berry Farm faces the threat of what many view as progress.

The Final Environmental Impact Statement, or FEIS, for Texas Central takes pains to address social, historic, and culturally significant properties that might be in the train’s path. That includes Freedman Colonies, land that was acquired and worked by Black families between the years of 1870 and 1930. The Morney-Berry Farm received a special designation from the Texas Senate for being farmed by one family for more than 100 years. But it is not included among the Freedman Colonies cited in the FEIS.

A few years ago, the family received a courtesy call from soon-to-be retired Congresswoman Eddie Bernice Johnson, suggesting that their land might be on the official train route. Five years passed with no meetings. There were no survey requests. It was almost as if Murdine’s children could put the whole thing out of their minds, until the Texas Supreme Court ruling just a few weeks ago.

A visit to the Texas Central website revealed that the Morney-Berry Farm is in the middle of the most current route. And now Texas Central, should it return to operations, has the power to seize the land.

Up until the ruling, the initial exuberance about the bullet train had gone flat. Observers and pundits have been betting against the project’s success.

The company claimed it had acquired or optioned about 40 percent of the parcels along the route, mostly small plots. Large property owners have held out. International partners fell away because of lackluster fundraising—according to the Engineering News-Record, the company has raised just $75 million and received a loan for $300 million from the Japanese to fund the estimated $30 billion project. A big negative for the partners in Spain, Italy, Mexico and Japan was the absence of support from Republicans legislators who did not want to isolate and anger the landowners along the train’s route.

In fact, it was Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton’s team that unsuccessfully defended the landowner in Miles vs. Texas Central Railroad & Infrastructure, the eminent domain case that gives the privately-owned company the right to capture property.

A bullet train has never been built anywhere in the world without public funding and massive political and popular support. No matter that Texas Central, the first bullet train in the U.S., would create 10,000 new jobs during each year of construction. The company claims it would create 1,500 permanent jobs and lift Texas into the major leagues as one of the world’s great centers of commerce.

But for politicians, it is a simple calculation: taking land from rural owners loses votes. Lots of votes.

In theory, this new ruling puts the company back in play. FTI Consulting, or whoever ultimately takes the lead, needs to rebuild, re-enroll international partners, and raise the $30 billion in current dollars that it will take to complete the project. It’s a big lift. Even for wide-eyed, business-friendly Texas.

Morney-Berry Farm is as much a remnant of another time as it is a farm. It’s no Colonial Williamsburg, more a reconsideration of the harsh period of the incarceration of human beings who suddenly were wearing the complicated garments of freedom. The one-room houses, once maintained by Murdine’s 80-year-old hands, are in need of repair. But each tiny house is filled with treasure.

Members of the surrounding community have over the years donated old pots, cutlery, threadbare quilts, hand-stitched dolls, photographs, rickety tables and chairs that have been passed down through the generations. It’s also the community’s unofficial gathering place. The open-air pavilions were created for neighborhood suppers. Weddings. Family reunions. For more than 20 years, folks from all over the region have congregated there for Juneteenth celebrations.

Sitting in the pavilion on a steamy Saturday morning, sipping cool water and looking at family photographs, you can almost hear the rich laughter, friendly ribbing, and child patter of the generations. For now.

Get the D Brief Newsletter

Author