Last month, with a Facebook post bragging about its seizure of $100,000 in cash from a Love Field traveler who has yet to be charged with a crime, the Dallas Police Department sparked a conversation it didn’t seem especially eager to have. Instead of praise for Ballentine, the good dog whose nose sniffed out the cash in a 25-year-old woman’s luggage, police found themselves fielding variations on a question: Wait, you can just take that money?

They can. In response to questions from reporters after that story went viral, police mostly declined to elaborate.

But on Tuesday night, police officials met with a community oversight board to talk about civil asset forfeiture, the means by which law enforcement agencies across the country take possession of property or currency they believe to be connected to criminal activity.

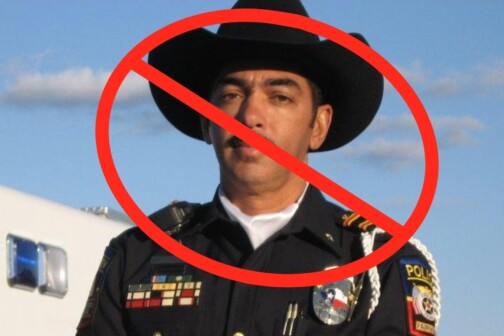

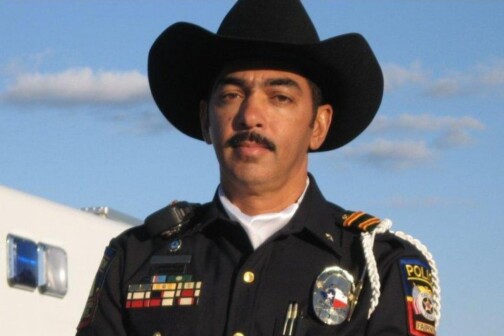

Deputy police Chief Thomas Castro, without citing specifics, said much of the local reporting and “tweets” that followed the controversy over DPD’s Love Field arrest last month were inaccurate. Civil asset forfeiture laws are an important part of a police department’s crime-fighting toolkit, he said. “By seizing assets, we’re disrupting, dismantling, and deterring those who commit crime and are conceiving to gain profit from it.”

The officials declined to answer questions about the Love Field case, saying that it remained under investigation by federal authorities. But they said officers do not seize property without probable cause, as determined by a judge or the officers themselves.

“We are not out here taking people’s money for no reason,” police Maj. Devon Palk told the board.

Palk says that in 2019 Dallas police seized more than $843,000 in cash and 29 vehicles in 159 civil asset forfeiture cases. In 2020, there were 174 cases resulting in $979,000 and 15 vehicles being seized. In 2021, Dallas police seized 16 vehicles and more than $2.3 million.

Those are state cases. Assets seized in federal cases wind up in a federal “equitable sharing program” that pays out to state and local agencies.

Officers do not receive any kind of bonuses or direct compensation for seizing cash or property, Palk says. The Dallas Police Department instead spends confiscated funds on undercover operations, software licenses, overtime, and equipment expenses. Palk mentioned Ross Perot Jr.’s recent splashy donation of a helicopter, which required some “equipment upliftment” to be paid for with seized assets.

“We are not doing this to try and increase our budget,” Palk said.

It is true that people who have their cash or property seized by Dallas police can get it back, if police or prosecutors determine they don’t have a case. With state cases, there must be an “underlying crime” connected to the seizure, but no “companion arrest” is required in federal cases like the one at Love Field.

Regardless, the forfeiture of property is a civil action, not a criminal matter. Officials did not directly answer a board member’s questions about whether the onus is on a property owner to try and get their property back. But, because the civil case proceeds separate from a criminal case that may or may not result in a conviction, it is by its nature the property owner’s problem. And because civil courts don’t guarantee property owners a court-appointed lawyer, contesting a seizure often comes with its own costs and hassle separate from any related criminal case.

A 2019 Texas Tribune investigation of 560 forfeiture cases found that “in about 40 percent of cases, no one who had property taken from them was found guilty of a crime connected to the seizure.” Nearly 60 percent of the studied cases went uncontested, with the seized property defaulting to the local government.

That number is even higher in Dallas. Castro told board members that 70 to 75 percent of forfeiture cases end in a default judgment, in which the property owner doesn’t participate in the civil case and the assets stay with the police department. Dallas police win another 10 to 15 percent of cases.

“[There is] maybe 5 percent or less that’s overturned and given back to the individual,” Castro said.

Per that Texas Tribune report, police in Texas don’t have to disclose “data on how much is taken in individual seizures, and how often they are tied to a criminal charge.” And police officials on Tuesday did not share that information with the oversight board.

DPD policy does prohibit seizing cash that amounts to less than $1,000, and officials said that “cash in and of itself is not suspicious.” To determine probable cause for an asset seizure, investigators will also weigh “behaviors, travel patterns, things like that, that may be indicators something more may be afoot here.”

How’s that for transparency?

“I’m still not clear how much money I can carry in an airport and how I need to behave to avoid having my assets seized,” board member Brandon Friedman said.

Get the D Brief Newsletter

Author