Charley Pride died Saturday morning, the latest casualty of COVID-19. The country music legend went to a hospital in late November with symptoms, his family said Sunday, and never recovered.

Just a month earlier, on November 11, he had performed at the CMA Awards after receiving the organization’s Willie Nelson Lifetime Achievement Award. Some are wondering now if his appearance at the ceremony, held indoors, might have led to his contracting the virus. If so, it would be a sad twist to Pride’s story. He had been keeping his name alive on his own long after country music had mostly turned its back on him. It would be darkly ironic if he died because Nashville, at long last, remembered him again.

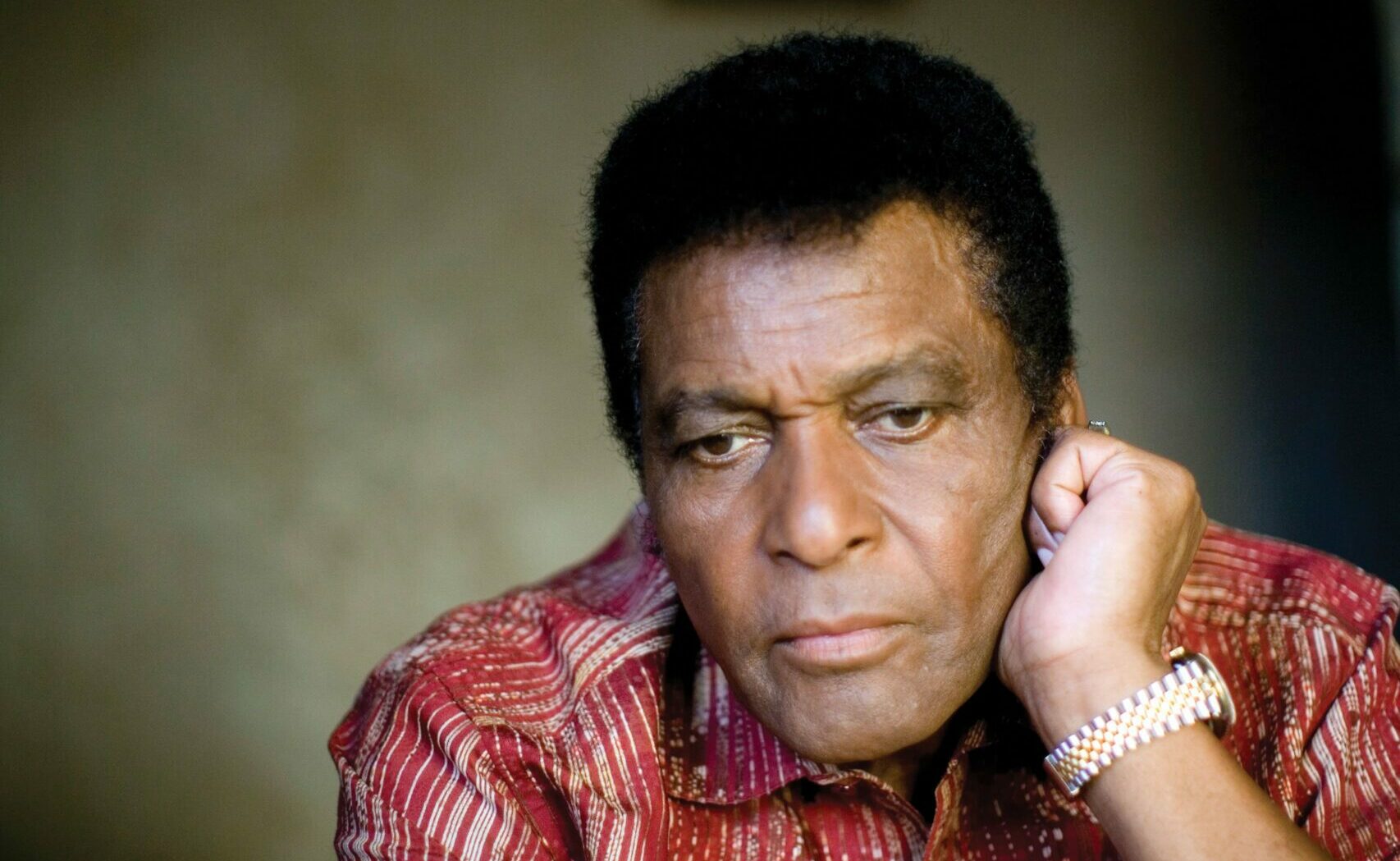

I profiled Charley for this magazine in 2008, and throughout the time I spent with him, he reminded me of his bona fides. The highlights: he was the only Black singer in the Country Music Hall of Fame, and, with somewhere around 70 million albums and singles sold, he was second only to Elvis Presley (ever heard of him?) in all-time sales on RCA. Even when Charley wasn’t saying it, he was doing it in other ways. While I followed him around during his yearly trip to Rangers spring training—he had almost made the majors before turning to singing—his phone rang and the ringtone was “Kiss An Angel Good Mornin’,” his signature hit. Back in Dallas, at the sprawling house he and his wife Rozene had lived in since the early 1970s, just off the Tollway, he had a stack of Charley Pride 8-track tapes near his living room stereo.

Charley was still a huge star in Ireland of all places (thanks to him braving the height of The Troubles to perform there), but he had been languishing on smaller labels since leaving RCA in 1986, a move he long regretted. He was still selling at least 250,000 copies when he released a new album, but he bridled at the way the label was treating him. So he asked to be released from his contract, as a negotiating tactic.

“What happened?” he told me. “Boom. They accepted it.” He laughed. “I tried to use a little expertise, or whatever you want to call it. Didn’t work out that way.” And so Charley found himself out in the wilderness a little bit. What he had done was revered. What he was doing was ignored.

It was a sort of dream assignment for me. My parents had been telling me about him for years. They saw him in Wichita Falls in the late 1960s, opening for Merle Haggard. At that point, Pride had charted with a few songs, but he wasn’t a huge star yet. That would come in 1969, when he had the first (“All I Have to Offer You (Is Me)”) of more than two dozen No. 1 hits on Billboard‘s country singles chart—an incredible run of success that would last until 1984.

My parents were blown away by Charley’s set that night, but the part they would always talk about is what happened after. The way they told it, Haggard came out late, obviously drunk, and definitely ornery. He didn’t make it through one song before cursing at his band and the crowd and leaving the stage. And then Charley came back out and saved the day with another set, even better than the first.

There was something unsaid but definitely present in that story, existing between the lines, just on the verge of breaking through: Charley Pride was so good that he, a Black man making his way through an almost uniformly White world, was able to steal a show from Merle Haggard not once but twice. A Black country singer shouldn’t have been that unusual, but it was then and mostly still is now. There is Jimmie Allen, who duetted with Charley at the CMA Awards, and Mickey Guyton and not many others.

“A lot of people say, ‘Well, you must have had it hard,’” he told me. “There’s not been one iota of that. Like when Jackie Robinson first went to the major leagues? No black cats, no name calling, none. I say this to reporters, and they look at me, and I say, ’Uh-oh, you’re giving me that I-can’t-believe-it-you-gotta-be-lying look.’ So I start naming off my accomplishments.” He wanted it to be known: his career wasn’t amazing for a Black country singer. It wasn’t even amazing just for a country singer. It was amazing, period.

The one time I saw Charley perform—about 40 years later—was less chaotic, but equally memorable and also under unusual conditions. I was working for the American Airlines in-flight magazine at the time. For reasons unknown to me still, Charley had been invited to perform at American’s Fort Worth headquarters. It was just him and his guitar, on a folding chair in the middle of an atrium in our building. I remember looking up and seeing employees leaning over railings from several stories up to get a better view. But you could hear him all over. His baritone, warm as springtime sunshine, was still in fine form then, as he neared 70 years old.

I wondered why the sort of late career re-appreciation that had come to his friends like Johnny Cash, Willie Nelson, and Haggard had escaped him. Charley never stopped recording—he released Music in My Heart in 2017, and he sounds as good as ever on it—but there was no Rick Rubin or Ryan Adams to keep him relevant like Johnny and Willie. I guess he wasn’t enough of an outlaw to land on a punk label like Hag. But I know his voice was ready to make a new batch of songs his own, and make a new batch of fans in the process. I could hear it that day at AAHQ, and you could still hear it at the CMA Awards, even in his mid-80s.

I’m glad the country music world gave Charley his flowers before he died. But I sort of wish they had waited until next year.