Editor’s note: this post was altered after it was published. For an explanation, go here.

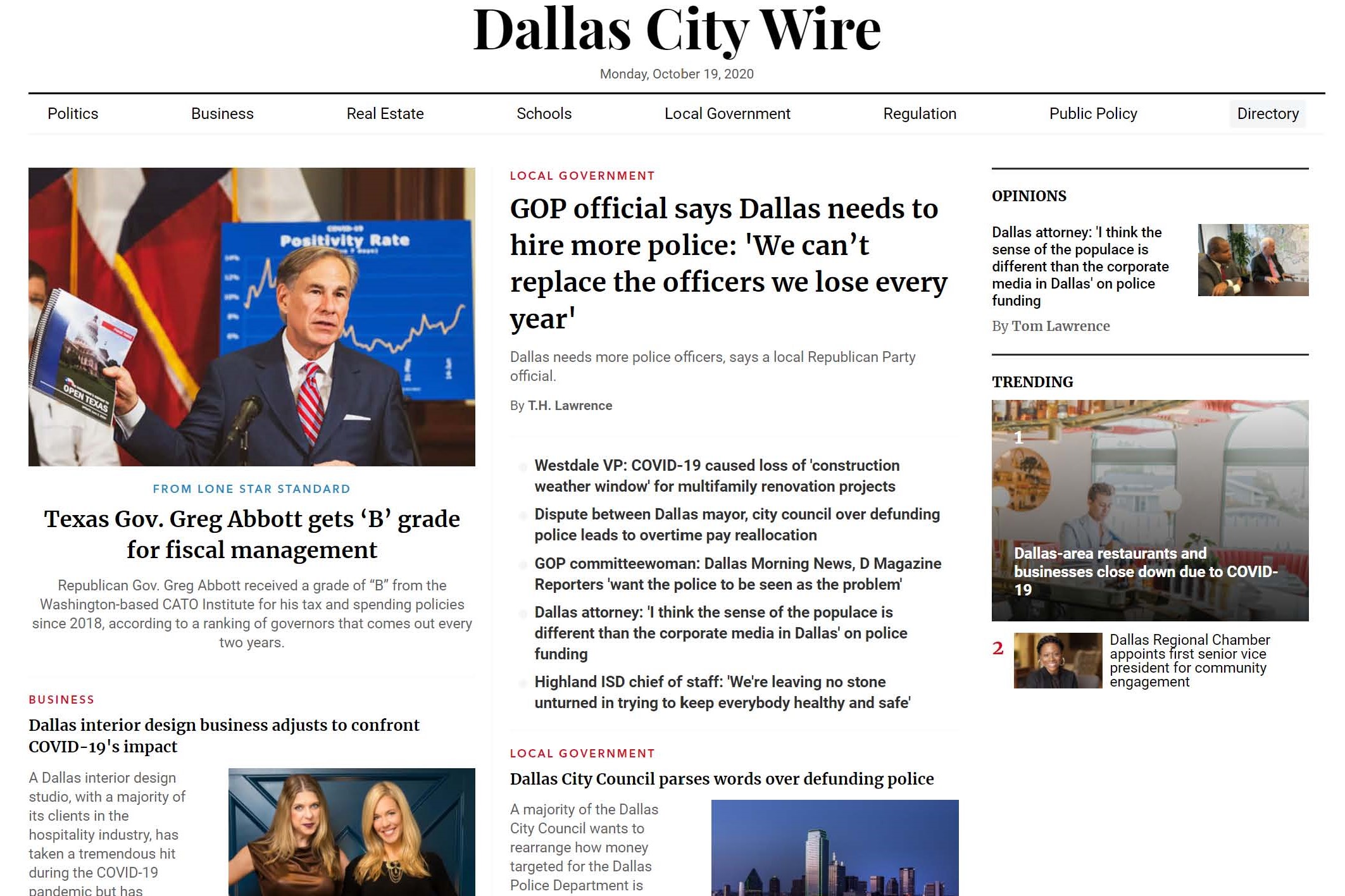

Perhaps in recent months you’ve stumbled across a local news story in your Facebook feed and clicked through to discover a new source called the Dallas City Wire.

Or, perhaps another story led you to the NE Dallas News, or the Ft Worth Times, or the SE Dallas News, or the North Texas News, or the West DFW News, or even the Nortex Times. If so, then you have stumbled into a shadowy new network of pay-to-play propaganda news sites that have rapidly proliferated over the past year.

A New York Times investigation, following on previous work by the Columbia Journalism Review, has found a fast-growing network of more than 1,300 news websites that have stepped into communities all across the United States. They look like legitimate news sites and claim, as these local sites do, to “provide objective, data-driven information without political bias.” But much of the content is paid for by partisan interests:

“[T]he network, now in all 50 states, is built not on traditional journalism but on propaganda ordered up by dozens of conservative think tanks, political operatives, corporate executives and public-relations professionals,” the Times reports.

Here’s how it works:

Say you’re a hotel magnate and COVID-19 has ravaged your business. You’re angry, so you pitch a few articles from the DC Business Daily that tear into China and its failure to contain the virus. The best part: the DC Business Daily reporter calls to ask you for your thoughts on the topic. Then, you request a few more articles that advocate for the federal government to pass a stimulus package favorable to the hotel industry.

According to the New York Times’ investigation, that’s precisely what Dallas hotelier Monty Bennett did earlier this year before his publicly traded company became the biggest-known recipient of federal stimulus small business loans, sparking public backlash that forced Bennett to eventually return the federal money. After that bad publicity, Bennett pitched more articles published on local news websites that cast him and his company in a positive light, according to the Times.

This kind of operation may go against every tenet of journalism, but it is the central business model established by Brian Timpone, a Chicago-based former local TV reporter who has quietly and quickly established a massive network of local news websites. Timpone’s name last surfaced in national media when he was featured in a This American Life episode about a previous company he founded that was trying to develop AI bots to replace local news reporters. His new company pays real people anywhere from $3 to $36 to write the news stories, but the content, angles, and perspectives of the articles are often dictated by clients who pay upwards of $2,000 for favorable content packages:

While Mr. Timpone’s sites generally do not post information that is outright false, the operation is rooted in deception, eschewing hallmarks of news reporting like fairness and transparency. Only a few dozen of the sites disclose funding from advocacy groups. Traditional news organizations do not accept payment for articles; the Federal Trade Commission requires that advertising that looks like articles be clearly labeled as ads.

Partisan-run “news” sites are not new, of course, and while the websites linked to Timpone tend to publish news biased towards the right of the political spectrum, liberal organizations have funded similar media sites. But what sets Timpone’s network apart is both its size—it is now twice as large as Gannett, the nation’s largest newspaper chain—and the lengths it goes to obscure the source and funding behind content.

Most of the sites declare in their “About” pages that they to aim “to provide objective, data-driven information without political bias.” But in April, an editor for the network reminded freelancers that “clients want a politically conservative focus on their stories, so avoid writing stories that only focus on a Democrat lawmaker, bill, etc.,” according to an email viewed by the Times.

Some of these websites operate almost like opinion news sleeper cells. They publish a steady stream of automated content until an event of local interest sparks the paid-content machine to life. Earlier this year, as protests erupted in Kenosha, Wisconsin after the police shooting of an unarmed Black man, the Kenosha-focused site linked to Timpone’s network broke from the cookie cutter content to publish reports on the criminal backgrounds of both Jacob Blake, the man who was shot, and some of the protesters. Those articles that reached millions of readers via Facebook.

Timpone did not speak to the Times, and many of the reporters and editors the paper reached out to said they had signed agreements that restricted their ability to speak about the company and its operations. It is, therefore, difficult to know how many paying clients Timpone’s network has, who they are, and how are using the network. But tax records and campaign-finance reports showed that the network received at least $1.7 million from Republican political campaigns and conservative groups. Internal correspondence received by the Times found that “assignments typically come with precise instructions on whom to interview and what to write. . . . In some cases, those instructions are written by the network’s clients, who are sometimes the subjects of the articles.”

A quick perusal of the North Texas-tagged websites that are part of the Metric Media News network — only one of the news networks the Times links to Timpone — shows that most of the sites publish content fed through by two parent sites. Many are written by a reporter who also contributes prolifically to other Metric Medias sites around the country.

Many of the stories appear to relate to COVID-19 — either advocating for a loosening of COVID-19 restrictions or praising reopening efforts by local schools. The Dallas-centric parent site is currently dominated by stories featuring local GOP officials weighing in on the debate over police reform (including one piece that accuses me of wanting “the police to be seen as the problem”). Another piece is about a Dallas-based pro-police funding group whose supposed founder—a woman named Renee Dewer—has no discoverable public presence via the public records database Nexis.

What I found most troubling about all of this was how unsurprising it all feels at this point. The local news industry has been in decline for years, and Google, Facebook, and others have long siphoned away the local advertising dollars that sustained the journalistic ecosystem. As Matt reported last week, one of the big reasons the Dallas Morning News staff is unionizing is to simply try to ensure that employees don’t get screwed with skimpy severance packages during what we can only assume will be the next inevitable round of layoffs. The city’s only daily has seen an incredible amount of turnover this past year, and there remain key beats — like Dallas City Hall — that have sat unfilled for months.

In other words, this isn’t a story about local news is dying — it is a story about the bottom feeders who are moving into the space to feed on the scraps. And because of the way information networks have been constructed, the business models that work in our current information age are ones that are designed to further erode journalistic norms, reward information manipulation, sow distrust, and further chaos and strife.

We’ve already seen what this new environment of media disinformation can do on a national level. How will it play out in a local context? My prediction: not well. Not well at all.