As I’m typing this on Wednesday afternoon, the air in the Joppa neighborhood of southern Dallas is about three times as polluted as what UT Dallas students are breathing up in Richardson. It was difficult, if not impossible, to compare those two things before this week. The SharedAirDFW Network now offers new insight into daily pollutants in a few North Texas neighborhoods with the goal of expanding its monitoring reach more than tenfold.

It took three years of grant applications, donations, and planning—and even more years of research—to pull off what one environmentalist described as a “garage sale-funded moon mission.” The air monitoring network uses a series of stationary sensors to determine the amount of particulate matter in the air, segmenting them by size of said pollutants. The network launched with eight sensors in southern Dallas, Mesquite, Richardson, and Fort Worth. It has plans for 100 more in the next two years and can expand even further with more funding.

Known as PM, particulate matter includes all manner of microscopic pollutants emitted by cars, plants, construction sites, unpaved roads, fires, and many other sources. Their size is important. When small enough—2.5 micrometers for instance, which is about 100 times smaller than a human hair—these particles can get into your bloodstream through the lungs. They have been linked to respiratory symptoms like asthma and neurological problems like Alzheimer’s. For neighborhoods like Joppa, which is next to a concrete batch plant and other polluters, knowing how much particulate matter is in the air could help adjust behavior. And public policy.

When people live and work in or near such poor air conditions, adverse effects are more likely. Think of the research into lead exposure via gasoline emissions and the associated complications: everything from hyperactivity to attention deficit disorder. The more you’re breathing this stuff in, the greater the chance of harm.

“If there are particles in the air, and especially those smaller ones, they can get into our bloodstream and into the brain,” says Dr. David Lary, an atmospheric scientist and a University of Texas Dallas physics professor who has led the project. “The particles are like a Trojan horse for getting into our brains. I don’t think any of us want that.”

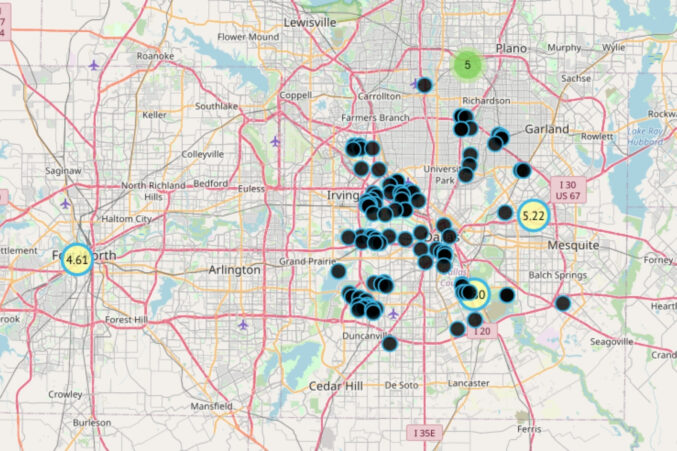

SharedAirDFW houses its data on an easy to read interactive map—programmed by friend of D Robert Mundinger—that can help people gauge how bad the air is near the meters. It updates every minute or so and includes the locations of operating permits for polluters, like concrete batch plants and factories. The map includes the amount of particulate they’re permitted to expel, and the sensors pick up what’s actually in the air.

You can see where a PM reader might be beneficial: so many of these polluters are concentrated in southern and West Dallas, as well as along the Stemmons corridor up to Irving.

The initiative is a collaboration between UT Dallas, the environmental justice nonprofit Downwinders at Risk, the city of Plano, Dallas College (the rebranded community college district), and Paul Quinn College.

Lary sees this as a next step in air monitoring. Currently, the Environmental Protection Agency has three particulate matter readers across North Texas. They’re quite accurate, but they’re also quite expensive—in the six-figure range—so they aren’t deployed to as many neighborhoods. Lary says the program is currently funded for “a couple hundred thousand dollars,” far cheaper than what the EPA’s monitoring would cost. There are about a dozen similar “Purple Air” monitors around the region, but those also aren’t updated as quickly as they would like and aren’t as accurate.

“The EPA actually told us that what we’re doing they’ve only dreamed about, which is a compliment,” Lary says. “We’re actually partnering with them.”

The closest EPA PM reader to Joppa is at the Kay Bailey Hutchison Convention Center downtown, about seven miles north. While noble, it doesn’t do Joppa’s residents much good.

Technology has improved in recent years, of course. SharedAirDFW uses machine learning to calibrate a network of less expensive nodes against a reference sensor. An important part of that calibration is accounting for temperature, humidity, and pressure variations over an extended period, so they can still make accurate readings whether the temperature is in the 40s or the triple digits. This takes about six months.

In Joppa, residents are volunteering to place monitors in their backyards. The reference sensor lives atop an old utility pole that Downwinders purchased from Oncor; the city wouldn’t let them use any of its poles.

“Maybe that was for the best,” says Jim Schermbeck, the director of Downwinders at Risk. “We have more control over where we put these things.”

Joppa has long been a priority for Downwinders. It’s a self-contained neighborhood of about 500 residents bordered by the Trinity River to the east and the Austin Asphalt batch plant and Tamko Building Products factory to the west. Somewhat famously among activist circles, in 2018 Downwinders rushed to Joppa with a particulate matter reader ahead of a City Council zoning vote that would have allowed two new batch plants. The group presented its findings and the City Council voted it down; there were already enough contaminants in the air. Without the PM reading, the evidence would have only been anecdotal.

Joppa, Schermbeck says, is “under-organized” and has lacked a “green” middleman to stand up for it. Which is why those polluters are in its backyard. Its size also makes it perfect for the SharedAirDFW network. Put the reference censor—which Schermbeck calls “the mothership”—on the pole, fan out the others in the neighborhood, and you’ll get a pretty good idea of how dirty the air is across the entire community.

His next neighborhood is more of a challenge. West Dallas is far larger. There are about a dozen polluters between North Riverfront and Loop 12, most of which are concentrated to the west of Westmoreland Road below Singleton Boulevard. That will likely require more sensors and a more creative strategy.

“Joppa was nice and contained; West Dallas is large and covers miles and miles,” Schermbeck says. “How far from the mothership can we put these things?”

It will be a challenge, but that question signals progress. For Lary, who began studying atmospheric science around the time we learned there was a growing hole in our ozone, this is another step to better understand the environment in which we live and that we influence. The city of Plano wants to put these meters in parks and near highways to identify ways to reduce emissions and motivate residents to carpool or use public transit. Colleges can also take advantage of the technology, looping it into STEM programs and identifying their own risk factors. Paul Quinn is near a handful of polluters as well, even though most produce far less particulate matter than those near Joppa.

SharedAirDFW is starting small, but Lary believes it can grow into something larger with the right support.

“We want to be an open partnership,” he says. “It’s open data. It’s not for profit. If others would like to partner with us and would like to support it, we’d be very grateful. We’re not a political group. We’re just doing it for public benefit.”