Earlier this week, the Dallas Morning News and NBC 5 published a story in tandem with University of Texas researchers that identified the city’s neighborhoods most vulnerable to the coronavirus. They didn’t rely on testing data or even positive cases. Instead, these UT Health Science Center scientists analyzed the rates of chronic health problems that can predict the likelihood of a COVID-19 patient needing hospitalization: diabetes, heart disease, stroke, COPD, asthma, obesity. Most of the Census tracts with the highest risk factors were in southern and West Dallas, the very neighborhoods that faith leaders and public health experts were concerned about.

The researchers looked at these chronic health problems because we don’t have good data on the virus. Only this week did Dallas County begin releasing demographics of the patients who had tested positive, and that data came with the caveat that it represented just 65 percent of the total positive cases.

Researchers, scientists, public health experts, elected representatives, and journalists must work the edges to predict the spread of COVID-19, particularly in working-class communities of black and Latino residents with poor access to healthcare, healthy food, and nearby jobs. Those are the factors that contribute to the underlying health conditions, commonly referred to as “social determinants of health.”

“It’s not unique to Dallas,” says Dr. Brian Williams, the former Parkland surgeon who is helping County Judge Clay Jenkins craft the response to the virus. “The reality is, all the major organizations—the CDC, the WHO—there is no one collecting racial demographics about the response to the coronavirus. We do not know who is being tested broken down by race. We don’t know who is testing positive, who is getting sick, who is getting critically ill, who is dying—and we need that data.”

Earlier this week, our local governments reached an agreement with the feds that will keep the two drive-thru testing centers humming through at least May 30. But that also included an elbow-tap deal that Dallas wouldn’t ask for more tests. That means each—one at the American Airlines Center, the other at Ellis Davis Field House in Red Bird—can only process 250 per day. The county labs have the capacity for 160 a day. That isn’t nearly enough to grasp the scope. About 24 percent of Dallas County residents also lack health insurance, meaning many don’t have a primary care doctor that can steer them to a test.

“We’re still at this metered level where we don’t have enough tests either on the public side or the private side,” Jenkins said. “When people don’t have health coverage, then there’s not a pay source for medical providers to be in the community. You’ve heard me talk about food deserts, but these are often healthcare deserts, too.”

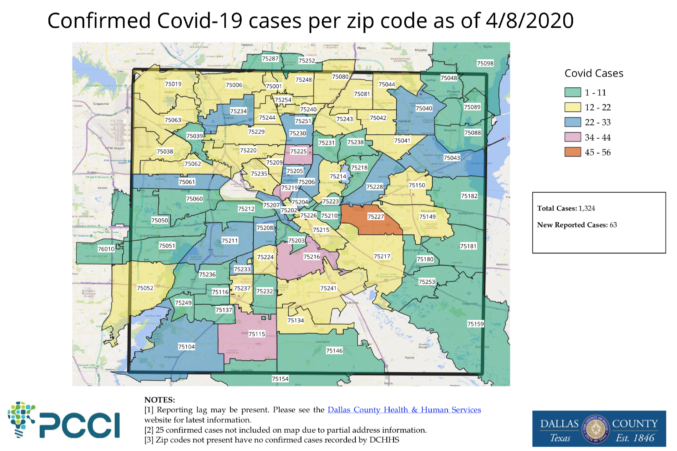

Making matters worse is just how bad the data are. The Texas Tribune reported that the state had released demographic data for just 33 of the 140 patients who had died from complications of a coronavirus infection. In Dallas County, 37 percent of patients are Hispanic. About 35 percent are black. And 26 percent are white. That’s a higher rate for black residents than their population share of 23.5 percent. And remember, more than a third of the total cases don’t have the demographic information. Dallas County still does not have raw data available, largely because of privacy laws, according to representatives with the Parkland Center for Clinical Innovation. PCCI has been doing the data mapping for the county.

“These populations, poor populations, and racial-ethnic minority populations—particularly the black population—have high prevalence of health conditions which increases the rate of death from this,” said Shannon Monnat, the Lerner Chair for Public Health Promotion at Syracuse University, who has studied this topic at a national level. “At the front end, not testing these groups at the same level is increasing the risk of fatality rates.”

Monnat published a research paper this month showing that states with larger shares of minority residents had lower testing rates for COVID-19. Early in the month, Texas’ testing rate per 100,000 people was among the nation’s lowest, hovering around 100. By April 9, it had increased to just 366 per 100,000, according to new figures published in The Atlantic. Per capita, that is the lowest rate in the nation. (New York, the highest, was about 2,000 per 100,000.)

So experts are going with what they know. Every five years, the county and Parkland Health and Hospital System create a community needs assessment. Last year, they identified the five unhealthiest ZIP codes in the city. Jenkins says he’s been in conference calls with hospital CEOs to serve these communities. In Wednesday’s City Council meeting, Councilwoman Carolyn King Arnold begged Dr. Philip Huang, who leads the county’s health department, to locate a testing center somewhere in 75216, which includes a wide part of southern Dallas, south of the Dallas Zoo to Loop 12.

Arnold’s ZIP code and 75115, home to the Ellis Davis testing center, each have between 34 and 44 recorded cases, among the highest in the south. But more telling is what is still missing: cases remain low in the ZIP codes around South Dallas. The largely Latino ZIP code of 75212 in West Dallas also has between one and 11 cases, among the city’s lowest. Is that because the virus isn’t there, or is it because there isn’t testing?

At this point, there is no way to know. So the county is preparing how it can. Jenkins has been up front in needing to work harder to reach Latino residents. He’s engaged Dallas Mexican Consul Francisco de la Torre to help spread the word, but many Spanish speaking immigrants told the News just yesterday that information is still lacking.

If they get sick, Jenkins expects them to seek care in an emergency room. And Williams wants everyone to be treated with the same respect and dignity in that moment. Which brings us to the Mass Critical Care Plan, detailed here by a number of prominent Dallas doctors. Hospitals are told to follow the sequential organ failure assessment score, or SOFA, in determining services and resources for patients if the system is overloaded. It’s meant to take out anything arbitrary—age is not a factor—and objectively use medical factors to make decisions based on an individual’s physiology, not a subjective determinant based on status.

Williams notes that this gives everyone an even playing field when they arrive at the hospital. “It’s prioritized based on need, not resources or status,” he says. “We’re doing our best to recognize everyone’s shared humanity.”

Doctors are being forced to use SOFA scores because our healthcare system is segregated, he says. That’s also why those UT researchers have to search for occurrences of co-morbidities to target their resources. We know the data are spotty and the testing isn’t up to snuff, so the strategy for prevention relies on targeting what we know: that there are huge parts of this county that need help, and need it fast.

“This will be a few weeks, a month, six weeks of high intensity work,” Williams says. “Then, after that, it’s time to do the work of really rebuilding and addressing the inequities that this virus has unmasked.”