Anga Sanders didn’t understand why it required a nonprofit to make fresh food available in her underserved neighborhood of South Oak Cliff. She’d consider the question while assembling a salad at the Uptown Albertson’s. Where were all the salad bars on Kiest?

The introverted human resources CEO is the founder of Feed Oak Cliff, a nonprofit that does what its name suggests: it offers fresh produce and healthy options to a neighborhood that needs it. Sanders, who was one of the first black students at SMU, isn’t blind to how the deep divides between northern and southern Dallas play out in terms of nutrition. She was willing to drive 12 miles each way to Uptown because, while there were other grocers in between, the variety of fresh produce and extensive salad bar couldn’t be found near her house.

She thinks the lack of fresh groceries in southern Dallas is about more than profit. “We have a lot of isms in this country: racism, classism, but this is place-ism,” she says. “[People in southern Dallas] eat chips, Cheetos, and honey buns, but why? Because that is what they have access to.”

Other areas of town have the opposite problem. Drive from the Snider Plaza Tom Thumb in Highland Park toward Mockingbird Station, a distance of just under two miles. There is a Kroger grocery store at Mockingbird and Greenville. Now, drive less than a mile down Mockingbird and you’ll find another Tom Thumb. A left on Greenville is just a mile away from yet another Tom Thumb and a Central Market, which is just across Lovers Lane.

In the wealthier and whiter segments of Dallas, residents drive past big box grocery stores full of fresh produce and affordable food so that they can get to another big box grocery store that they prefer. But in large swaths of Dallas, this is not the case. In 2018 the Department of Agriculture identified 88 separate food deserts in Dallas County. Over half of them were in three southern portions of Dallas. In these areas, the best option for food is often a corner or dollar store, which are both more expensive and less nutritious than the grocery stores that are on every other block in North and East Dallas.

Access to nutritious food is part of a larger problem around those areas’ social determinants of health, which include education, transportation, housing and healthcare deficits. A study by the University of Texas system found that residents in a South Dallas ZIP code had a life expectancy of 26 years fewer than those who lived in East Dallas. Those ZIP codes are just two miles apart.

“When your ZIP code can literally determine your life span, that’s a problem,” Sanders says.

High crime, low income, and a lack of other retailers are often cited as reasons for grocery stores avoiding food deserts. But soon-to-be-published research from University of North Texas professor Dr. Chetan Tiwari and market research expert Ed Rincón is dismantling pre-conceived notions about how these communities spend their money. Their report provides objective evidence that grocery stores are missing an opportunity to make money and improve the health of a city along the way.

The case for groceries

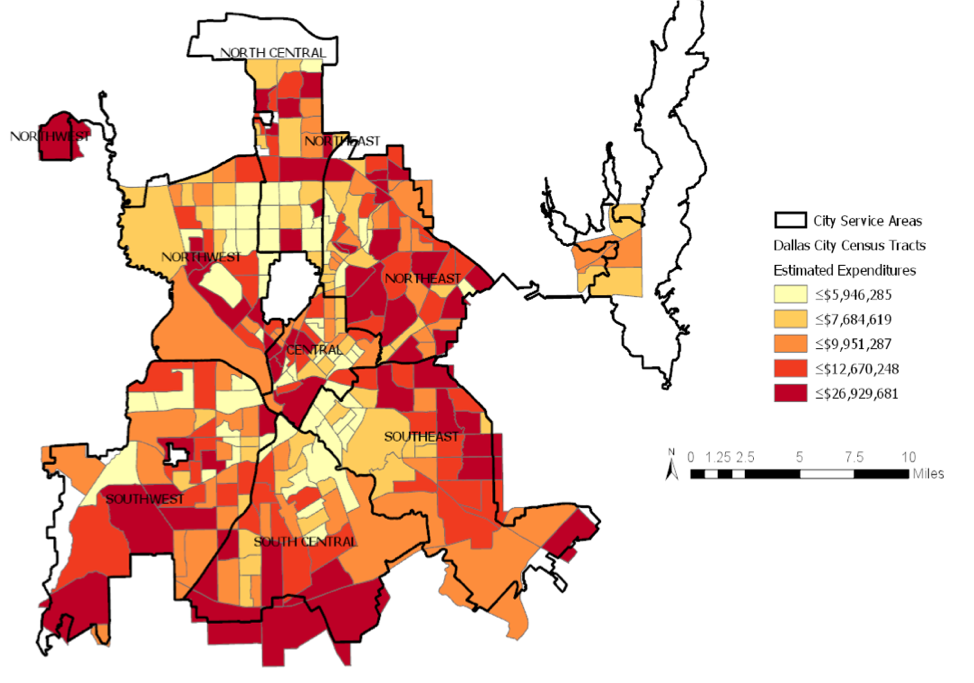

Rincón got curious about whether grocery stores could indeed turn a profit in poor neighborhoods. So he paired Census tract and crime data with the Food Marketing Institute’s 2017 Consumer Expenditure Survey.

The data finds that food spending does not correlate with income in the way spending on housing, cars, or other items does. Poor people have to eat, and because of where they buy their food, they end up spending a larger portion of their income on food than wealthy people. Rincón’s report also finds that money is being spent outside the communities where people live.

Data from Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) retailer data shows that more than 82 percent of all SNAP benefits were spent at supermarkets or supercenters, even though they only make up 14 percent of the locations that accept SNAP and are rarely located in the food deserts where residents are more likely to use the benefits.

Sanders’ anecdotal experience echoes Rincón’s data on food spending. “They say we don’t spend enough dollars in our community on groceries. Yes, because there is nothing here we want,” she says. Sanders often drives six miles to Cedar Hill, or into North Dallas for a Central Market, spending money outside her community. “They know that, but its handy to say we wouldn’t be profitable.”

“Retail leakage is being spent outside of the community and, crime data is inflated,” Rincón says. “No one has looked at it as closely as I have, and I make a case that there is money there.”

Rincón, whose background includes market research for grocery store chains, looked at how much households were actually spending on food, rather than just their income. He combined that data with SNAP expenditures to find more accurate food spending for various census tracts in southern Dallas.

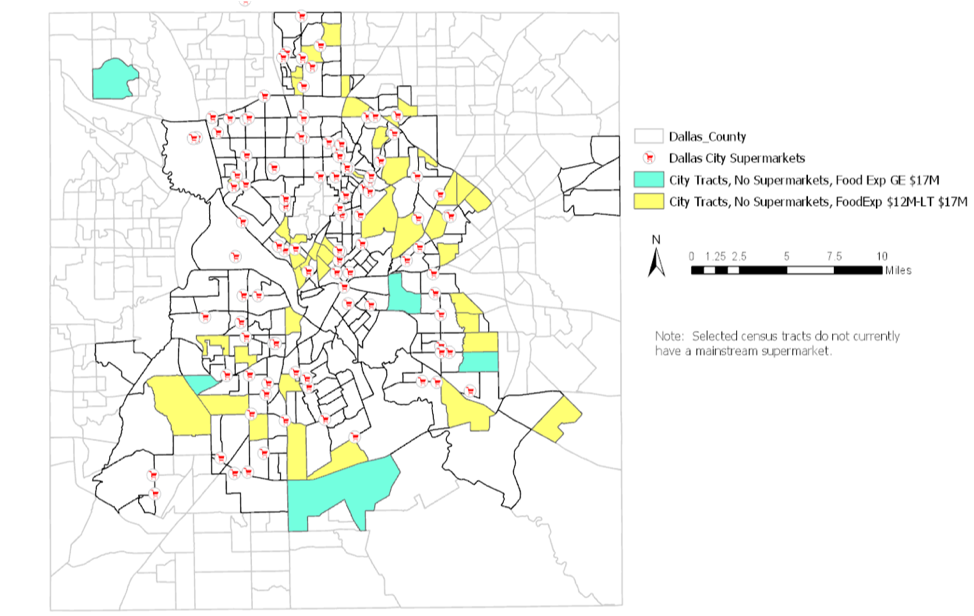

His research found several food deserts whose spending on food equaled or exceeded the amount a mid-size or full-size grocery store would need in an area to be profitable. Large stores usually have around $18 million in annual sales, while mid-size stores look for between $12 million and $17 million per year. Couple that with the fact that there would be little competition in those areas because of the lack of grocery options, and his data shows a missed opportunity for grocery stores.

Now, look at how the city and the big-box stores talk about making the numbers work. In 2016 the City Council offered $3 million to any grocery store willing to sell healthy food in a Dallas food desert. There have yet to be any takers. In the meantime, a Costco opened in near Lake Highlands, and two new Central Markets have opened in Preston Hollow.

So why won’t grocery stores move into the areas that need them most? In short, they believe they won’t be able to make any money there. Robert Wilonsky of the Dallas Morning News once wrote that “an H-E-B spokesperson told me in 2017 there just weren’t enough residents in targeted areas to support a big store. And, those who live there, south of the Trinity River, didn’t have enough money to make such operations sustainable.”

Rincón believes he’s poked a hole in that. In fact, he identified more than 40 Census tracts in Dallas that lack a grocery store but have the demographics and the spending potential to support one. Four, in fact, have the population to generate the $18 million or more in annual sales that grocers covet.

Another False Alarm

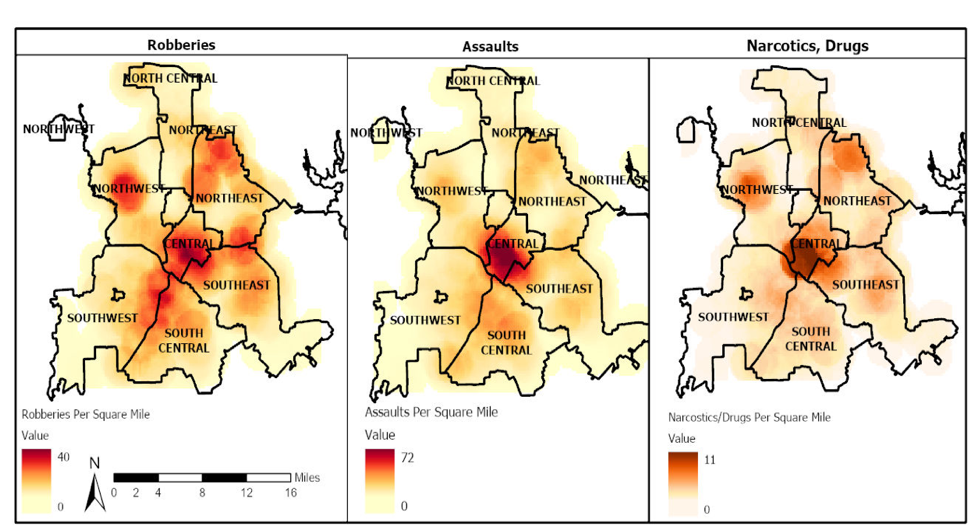

Crime is another dead horse beaten by the grocery lobby. The study notes that crime statistics cited by grocery stores are generalized and outdated.

“Decision makers rarely conduct any analysis of crime rates to justify their decisions, relying primarily on stereotypes or myths shared informally by peers or other associates,” the study says.

While food deserts overall did have higher crime rates than the city, this wasn’t the case for all of them. With a closer look at the crime data, the areas with the highest crime rates were actually in central and northwest Dallas, and many of the southern Dallas food deserts had no more criminality than other areas of Dallas.

“Many people conflate poverty with dishonesty,” Sanders says. “So they think they are poor and therefore dishonest. Poor mothers want their children to have a good shot at a higher quality of life, but if you can’t feed your child early during their formative years, then that child’s quality of life and length of life is capped off.”

If grocery stores were truly agnostic about where they were, who their customers were, and were out to make money, then they would have incentive to look as closely at food spending and crime data as Rincón.

“You would think it was an obvious step,” says Dr. Chetan Tiwari, an associate professor in Geographic Information Systems at UNT who worked with Rincón on the report. “Why aren’t grocers doing what we just did?”

Rincón’s data shows that food spending is high enough and crime is low enough to justify a mid or full size grocery store in several of Dallas’ food deserts, but getting to those grocery stores might be another hurdle. Many of the areas that suffer from a lack of healthy food also lack affordable and practical transit.

Rincón says that some stores have worked with transit to place stops nearby, while others have offered discounts to ride share companies if heading to the store. He could even foresee a store offering a courtesy van to drive people to the store to build up community goodwill and customer service. But those are just hopes. And besides, he says transportation has never come up when stores defend their placement choices.

“None of the recent interviews with supermarket execs pointed to transportation as an issue in Dallas area site location decisions — it is usually explained as high crime and insufficient income,” he says.

Rincón and others think the lack of stores is about more than just fears about profit.

“I use the term plantation politics,” Rincón says of the grocery stores. “They are making up lies and fictitious data to justify their decisions.” He has worked with grocery stores for location studies and has seen the prejudice firsthand. “Everybody has a profile of customers they want to serve,” he says. Once, while making a presentation about how a store could market to an audience of color, a grocery executive responded, “I am not sure we want that kind of customer.”

“There is a whole at system at play here that keeps the status quo the status quo,” Sanders says. “We are trying to break that cycle. I call it food injustice or food apartheid.”

A nonprofit answer

Sanders started Feed Oak Cliff with the vision of recruiting a grocery store to the neighborhood. After several discouraging and condescending interactions with grocery store decisionmakers, she is shifting her focus to start her own nonprofit grocery store in Oak Cliff.

It has worked elsewhere. Brook Oaks is a neighborhood in Waco that once featured a liquor store, an adult theater, and no grocery store to speak of. The low-income food desert is not unlike many neighborhoods in southern Dallas, full of convenience stores but no access to fresh and healthy food. Jimmy Dorrell, a minister and activist who has been working in the neighborhood for 40 years, wanted to do something to address the lack of food options. So he and his nonprofit, Mission Waco, made plans and raised funds for a nonprofit grocery store.

In 2016, the nonprofit transformed a convenience store into Jubilee Food Market, a 6,500 square-foot grocer in the former food desert. Jubilee and Mission Waco have helped transform the neighborhood. The adult theater is now a community theater, and one of the city’s most popular coffee shops, World Cup Café, is also nearby. A Fair Trade Market is here too, and an ice cream shop is on the way.

There are other examples. In Chester, Pennsylvania, Fare & Square became the nation’s first nonprofit full-scale supermarket in a 34,000-person city where there had not been a grocery store for more than a decade. More than 30 percent of Chester’s population live below the poverty line, and 35 percent of disposable income is spent on food, compared to 12 percent for the general population. Philadelphia nonprofit Philabundance helped launch a 16,000 square foot store in 2013, and it has since been purchased by a for-profit grocery chain, providing more evidence that this model can be successful.

But Rincón says grocers need to be creative with their product selection and marketing. They can’t just drop a normal Kroger frequented by a wealthier, whiter customer base into a lower income neighborhood. Balancing cultural preferences, profitability, and health is necessary to make these stores work.

“Some models don’t work well in communities of color, but there is evidence that others are profiting,” Rincón says. “They are going beyond is what traditionally done.”

For-profit grocery chains have the scale to operate on slimmer margins, which is why Rincón makes the argument for one to move into Southern Dallas. But can one-off nonprofit grocery stores be sustainable? Jubilee Market is asking for middle class shoppers to shop at the store once a month to help with costs, and, before Fare & Square was sold, leadership estimated that they would have to double sales to become profitable. A Food Marketing Institute Report said that grocery stores usually require $8 to $25 million worth of investment on the front end, and with profit margins under 2 percent for most stores, grocery store chains have reason to be cautious (Kroger and Albertson’s did not respond to questions for this article). This caution has pushed many in southern Dallas to look for a nonprofit alternative.

“I have spent my entire life here, and there were a lot of grocery stores around, but none of them exist anymore,” says Taylor Toynes, founder of For Oak Cliff, an education and advocacy nonprofit. His grandfather owned a grocery store in Oak Cliff. “The people who are making the decision, they don’t understand the food desert. We create beaches and lakes, we don’t go out and create deserts. But that’s what we are living in.”

Toynes, Sanders, as well as CitySquare Vice President of External Affairs Gerald Britt have all discussed a similar iteration in southern Dallas, though locations are still being scouted. Glendale shopping center, where Toynes’ grandfather once owned a grocery store, is a potential location.

While at first Sanders was wary of a nonprofit answer, she has come around over time. She is eyeing a couple locations that could serve as both a grocery style as well as a hub for local artisans. She wants the store to be successful and help her neighborhood but knows it may also serve as a signal to the big grocers that a store would be profitable. Rincón hopes his data has shown a path that for-profit grocers can follow.

“Once the store opens, the corporate stores are going to go, wait a minute, maybe there is a market,” she says. “We are the canary in the coal mine.”

Rincón and Tiwari’s paper, “Construction of a Demand Metric for Supermarket Site Selection: A Case Study of South Dallas”, is scheduled to be published in Papers in Applied Geography.