The city is at a crossroads. Dallas will elect a new mayor in the June 8 runoff. What solutions will the new mayor bring to old problems? What can be confidently known about Dallas’ political future is that the city’s Sisyphean planning to build a park in the floodway near downtown will continue. The city will need to ask for more money to realize those plans because, according to Sarah Standifer, assistant director of Dallas Water Utilities, the $246 million in bond money voters approved for lakes and parks in 1998 is “no longer in the drawer.”

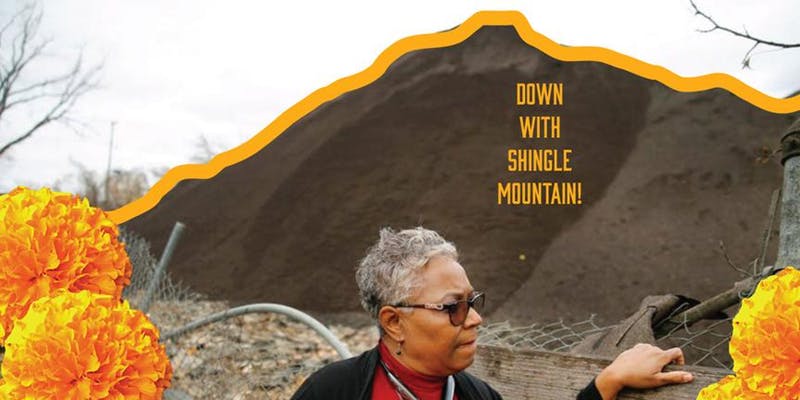

One way to challenge this tired narrative is to openly air the city’s history of troublemaking as it pertains to the Trinity River as well as to address the hard truths of environmental injustice. (The two are related; people who live in neighborhoods near the river know this all too well.) An upcoming event on Thursday, May 30, presents such an opportunity. The event, called “Together We Can Build Mountains,” is a fundraiser featuring Marsha Jackson, whose homestead sits in the shadow of Shingle Mountain. Others in attendance will include two of Dallas’ most enduring and accomplished troublemakers, Luis Sepulveda and Jim Schermbeck. The public is invited to attend, though reservations are required and seating is limited.

What follows is a Q&A with Jim Schermbeck, the director of Downwinders at Risk, one of four sponsors of the event. He and I talked about lead contamination, air quality, zoning, plans for a park, and all points in between.

LP: In the 1990s, you worked with Luis Sepulveda and the West Dallas Environmental Justice Coalition. It was a long slog getting the EPA to respond to the lead contamination. Did the ability to conduct your own tests make a difference? If so, how?

JS: Absolutely. Because without testing you don’t have documentation of attic dust with thousands of parts per million of lead in it. Without documentation, nobody official believes you.

Evidence of blatant lead-waste dumping was everywhere at the time. You could go to vacant lots and see piles of plastic battery casings the RSR smelter would dump down the road, which are remnants of the cases they had to break open to get the lead out. It wasn’t a secret in West Dallas — just everywhere else. But having the ability to get an EPA-certified lab to say conclusively this sample had 20,000 ppm of lead (or whatever it was at the time) jump-started the process. This is why it’s important for the best science to be used hand-in-hand with the best knowledge local residents have. Great technology is useless without it being directed at the right places. Great grassroots information is useless unless you can verify it.

This is the same reason Downwinders at Risk is now trying to build an independent, real-time network of high-tech, low-cost air monitors in Dallas. You’ll be unsurprised to find city staff is opposed to this idea.

LP: How is “environmental justice” different from other environmental or conservation issues?

JS: It’s the social justice wing, the public health wing of the environmental movement. Imagine a union not of employees of a specific trade but of air breathers, or water drinkers, where the purpose of the union is to protect membership from being poisoned by a system that’s forcing them to inhale or swallow somebody else’s crap. Now imagine such a system operating under the same rules of racism, misogyny, and bias that society as a whole operates under. Most of the time the people who are getting crapped on by pollution are the same people society craps on in other ways. To change that you not only have to eliminate the poisons, you have to change the way the system works—you have to bring those people excluded from the decision making to the table. In this way environmental justice is just old-fashioned social justice with a modern knowledge of chemicals and human health.

LP: How far has Dallas come since the lead issues in Cadillac Heights and West Dallas? How does that time period compare to recent gains in the Shingle Mountain incident?

JS: As a city, it’s hardly moved off dead center in terms of addressing Dallas’ fundamental environmental justice problem: separating people from polluters along the length of the Trinity River Corridor where Officialdom has crammed both “undesirable” industries and people side-by-side for decades. Southern Dallas can never shake off its racist past until the zoning that makes it the automatic dumping ground for polluters is removed. That zoning allowed three lead smelters to operate along the Trinity River in West and South Dallas up until the 1980s. It allows slaughterhouses. It allows places like Joppa and Singleton Boulevard. 99% of all of DFW’s landfills are located next to the Trinity River. It allows batch plant after batch plant to go south of the river with no objection from city staff. And it allowed Shingle Mountain to happen.

If you take that status quo and add a Dallas city government that is only reactive in its policy making, you have the current situation. City staff is not out and about trying to solve this problem or address its symptoms in any way. The Southern Sector Rising Campaign had to threaten civil disobedience during an election season just to get their serious attention about a huge six-story-high, 70,000-ton illegal dump [i.e., Shingle Mountain].

Sitting on shelves at City Hall are master plans for these neighborhoods that discuss the need to de-industrialize the river corridor but no one at City Hall seems to have read them. Staff just keeps making the same recommendations to dump polluters in the same neighborhoods — even as they proclaim their newfound concern for black kids with asthma. It’s up to the neighborhoods themselves to enforce the visions of those master plans.

LP: Why is it important to help build neighborhood coalitions? Can you tell me a little bit about the Shingle Mountain group, Southern Sector Rising Campaign?

JS: Neighborhoods groups have staying power and built-in self-interests. They’re formed to protect and defend. They’re already a “union” of residents who often know what they need to do to make things happen to get a stop sign or streetlight. If you can focus that energy on decreasing the amount of crap they and their kids breathe, you have a powerful force that City Hall recognizes in traditional, power politics terms. These aren’t Sierra Clubbers or Greenpeace kids. They’re residents who vote and can make problems for City Hall because they aren’t stereotypical “environmentalists.” They often don’t look at themselves as environmentalists; they say they’re just fighting for their rights. And they’re correct.

Only three months ago, there was no Southern Sector Rising Campaign for Environmental Justice. The city of Dallas is directly responsible for its formation. It was created only after the city blew-off Marsha Jackson’s complaints about Shingle Mountain from December through February and a group that was already meeting around environmental justice issues in Joppa turned its attention to helping her. Because her situation was so extreme, the decision was made that extreme escalation was needed. A call to action went out. The resulting group decided to mount a short-term campaign designed to put pressure on the city just as Earth Day activities crested in April. It was decided we’d begin with a news conference announcing our intention, followed by weekly pickets, followed by a residents’ blockade of trucks at the site. As it turned out, all it took was the news conference. From beginning to that end, it took 30 days.

Strong women — Marsha Jackson, Temeckia Derrough, Stephanie Timko, Miriam Fields, Justina Walford, and Sister Patricia Ridgley — made up the decision-making core of the group and are responsible for its success. Operating in crisis mode, where every day is another roller coaster ride, I’ve never seen a group of people respond better as a unit than this group when the pressure was on. They never took their eyes off the prize. Now that they’re turning their attention to systematic rezoning, City Hall should watch out. Dallas has never seen a group like this before.

LP: How does zoning and enforcement fall within the endless planning scheme for a park? What if we never build anything but, rather, made sure folks along the river don’t get poisoned?

JS: A 200-acre downtown park along the Trinity, almost all along the levees, will have zero impact for most people living along the Corridor. To do this right, Dallas has to look at the entire length of the Trinity River and its branches as it runs through the city. Doing it piecemeal based on foundation gifts will never get you the systematic change that’s needed, and it will always put Southern Dallas last.

LP: What are people supporting if they buy a ticket to the event on May 30? Scott Griggs will be there. Has Eric Johnson responded?

JS: First and foremost, a ticket holder is standing in solidarity with Marsha Jackson and the Southern Sector Rising Campaign. Not just to clean up the mess at Shingle Mountain, but to begin the hard work of re-zoning all of the Trinity River Corridor. I don’t know of another group that’s as explicit about this goal as the Campaign. They’re taking a very large, 70,00-ton “negative” at Shingle Mountain and pushing it hard enough to make an even larger “positive” — rezoning not just that tract but re-writing Dallas’ entire relationship with the Trinity River.

Second, you get a whole lot of fun and Big Thoughts for that good cause. You chow down on Graham Dodds’ food while watching great dance and musical acts you’d never see performing together at one of the most unlikely event venues in the city — at the very foot of Shingle Mountain. You get to hear Luis Sepulveda tie West Dallas and Shingle Mountain together. You can listen to Robert Wilonsky retrace the story of how he became an unpaid city environmental staffer. You can listen to Scott Griggs explain how he’d avoid another Shingle Mountain if he becomes mayor.

Along with everything else going on that night, we’re also holding our annual graduation ceremonies for the College Of Constructive Hell-Raising, so you’ll get a glimpse of how Downwinders at Risk churns out new organizers for a variety of causes in Dallas year after year.

Eric Johnson’s camp has not responded as of this Monday morning. They’ve had two weeks.