On November 30, the Dallas Morning News published an editorial titled, “Don’t let Preston Center become an anchor holding Dallas back.” The piece narrowly focused on the decrepit central garage in Preston Center—a big problem and equally big opportunity—while ignoring the greater Preston Center area, and the actual anchor holding it back: former Dallas Mayor Laura Miller.

Instead, on December 8, the News published a guest editorial by Miller that Councilwoman Jennifer Staubach Gates called out in a tweet: “@DMNOpinion published a column by Laura Miller today that is filled with inaccuracies and misinformation regarding Preston Center…”

Who’s right here?

Let’s Review Miller’s Preston Center History

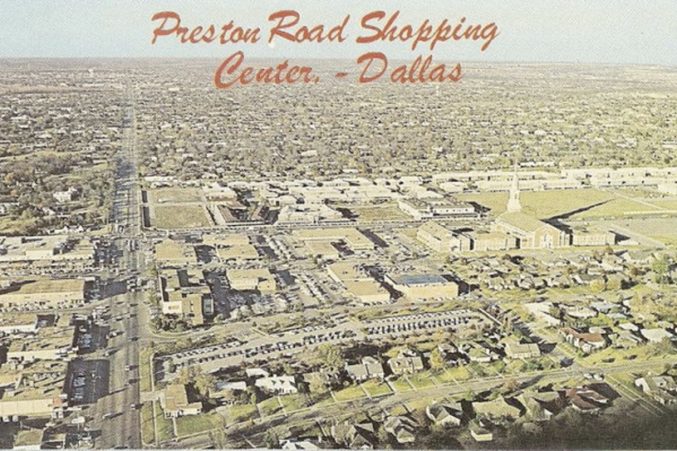

Preston Center is today much the same as it was 50 years ago—minus the anchor department stores that have vanished, taking foot traffic right along with them. It’s an aging shopping center dominated by a central garage where most people, typically from surrounding office buildings, go for lunch and little else. This is something Gates is trying to change. Given the complex ownership structure of its buildings, this is difficult to achieve.

There are ongoing attempts to bury the decaying garage and bring a Klyde Warren-esque feel atop it. Projects proposed in recent years attempted to increase the residential component of the center, which would likely bring more people to the area at more times in the day and night. These proposed developments offered better sidewalks, improved streetscapes, and more quality retail. The consultants employed two years ago as part of an area plan for Preston Center made the same recommendations to revitalize it. And Miller has fought nearly every one of them.

I’ve spent several years covering development surrounding Preston Center. I remain unable to explain Miller’s continued opposition, and she has not spoken publicly about the source of her concern. As I’ve written about Preston Center and spoken with other stakeholders, they too remain confused by her actions. In an absence of explanation, all I can do is report on visible actions.

Let’s start in 2014. Developer Luke Crosland wanted to build a residential high-rise in Preston Center called Highland House, which largely targeted wealthy empty nesters. Almost immediately, Laura Miller mounted a campaign to kill it. It worked. Crosland sold the property to Miller’s pal Leland Burk (to whom I heard Miller whisper “Don’t worry, you’ll get your high-rise” concerning the same property at a task force meeting. And, in April 2018, Miller waved around Burk’s lowball offer for Preston Place, shaming owners for not taking it). The Dallas Observer published a very good feature back then about this mess, which provides plenty of detail about how it all came about.

Also in 2014, Transwestern began the long process of constructing an apartment building at the northeast corner or Northwest Highway and Preston Road. Again, Miller became a central opposition figure on the protracted battle, which at one point had been reported dead by Laura Miller’s hand. It ultimately succeeded in passing Plan Commission and City Council and has been built.

In 2015, Harlan Crow wanted to construct a pedestrian bridge from the Preston Center central garage to his property’s second floor to safely transport shoppers to a new Tom Thumb grocery store. Crow had volunteered to tear the bridge down at his own expense should the city ever decide to fix the parking garage. (The city owns it, but can only make parking changes with the unanimous approval of the buildings surrounding it. Just another complexity holding Preston Center back.) Again, Miller led the opposition (here, here).

When the Crosland deal came about, Councilwoman Gates formed a neighborhood group to study the existing conditions and devise a plan for the Preston Center area’s future. Some reported this was at Miller’s request. Meeting for the first time in March of 2015, the task force included Miller and resulted in the Preston Road and Northwest Highway Area Plan that was adopted by the city in December 2016.

There were almost two years worth of monthly meetings. About $350,000 was spent on consultants. By July 2016, Gates’ task force had effectively been steamrolled by Miller. It was Miller who brought together the rest of the task force members to meet in secret, out of public view, and devise their own plan, according to two members of the task force. The exhaustive (though confusing) research paid for by the task force was dumped or placed in an appendix. The task force wrote its own plan that met members’ own personal agendas and/or business goals.

Writing for CandysDirt.com, I shredded Gates and the task force. (April 2015, July 2015, October 2015 (1), October 2015 (2), October 2015 (3), January 2016 (1), January 2016 (2), January 2016 (3), January 2016 (4), February 2016, March 2016 (1), March 2016 (2), May 2016, June 2016, July 2016 (1), July 2016 (2), July 2016 (3), November 2016 (1), and November 2016 (2).

At the time, I was concerned about the research being conducted by Kimley-Horn and how it was presented. The data wasn’t user-friendly, which resulted in a complex delivery that confused everyone in the room. Repeated, detailed requests for simplification fell on deaf ears.

I could, however, agree on the essence of their recommendations for Preston Center. These included increasing residential occupancy, which would increase foot traffic and vibrancy. It shared a goal of decreasing the percentage of office space in order to mitigate traffic and change Preston Center’s appearance as a ghost town in the evenings and weekends. Think more West Village and less today’s office park/food court.

Once authorship was taken over in July of 2016, critics argued that the resulting plan was light on facts while stuffed with personal agendas. According to task force member Peter Kline, he and Miller co-authored the final version and he doesn’t classify it as a plan. “To call it a plan is an overstatement,” he said in an interview. “It was a series of compromises where everyone in the task force would sign off on the broad picture.”

I called out the plan’s recommendations for Zone One (which encompassed Preston Center) and Four (which ran from Preston Road to Hillcrest between Northwest Highway and Bandera, including the Pink Wall). The remaining zones were unchanged single-family areas.

Within the plan that was passed, Preston Center’s Zone One essentially reads like the status quo. Its landowner task force representatives didn’t want any changes. Zoning within Preston Center allows for significant untapped density and little oversight on what can be built—office, residential, whatever. Maximum heights there reach up to 17 stories.

The Pink Wall’s Zone Four was a similar do-nothing outcome. The plan offered to increase the existing three-story cap to four stories, but shrunk the amount of land that developers could build on. That one additional story is crumbs compared to the untapped potential for density in Preston Center. And like the rest of Miller’s Area Plan, the task force never studied whether four-story construction with smaller footprints was economically viable to build. It’s not. The recommended changes would effectively be a wash for developers—there wouldn’t be enough money in the new builds to warrant them changing what was already there.

Or to put another way, the only way to build four stories would be to cheapen the land and the resulting buildings so much so that the neighborhood would suffer depreciation. Cheapening the land to that extent would equate to a price below the cost to buy an existing condo on the open market. If the only ability to redevelop involves losing money, there will be no redevelopment until the properties have deteriorated enough to make the money work.

Backing that up, two financial studies have been provided by one developer (here, here). One was authored by Joseph Cahoon an adjunct professor and director for the Folsom Institute for Real Estate at SMU’s Cox School of Business. Hardly the sort of person who risks their professional reputation for a few bucks to placate a developer.

Kline echoed my feelings on the Pink Wall and the six parcel planned development district (PD-15, in city parlance, which includes the area between Preston Tower and Athena high-rises). Zoning in PD-15 is limited by the total number of residential units, with height being somewhat secondary. The odd density limitation is part of the ongoing neighborhood battle to redevelop the burned Preston Place and other complexes within the district.

“It was not studied in great detail,” the task force member said. “We never discussed the (planned development district) in the task force specifically. We did what the representatives said their residents wanted.”

In July 2016 I wrote, “There are decrepit complexes that can’t afford repairs whose only economically viable option is to be torn down. But within current zoning, redevelopment isn’t financially viable … the pipe dream sees a developer making a dime with less lot coverage in exchange for a piddly single additional story?”

But Gates Made a Mistake

Gates’ key mistake was likely believing Miller’s report wouldn’t matter. That, like its 1980s counterparts, it would sit on a shelf collecting dust. It may have been why Gates allowed Miller to ride roughshod over her task force and craft the self-serving plan. It was a grave miscalculation that revealed itself all too quickly.

In December 2016, three months after the city adopted the task force’s plan, calamity hit the Pink Wall. Preston Place burned down. Six months later, a developer came forward for the neighboring Diplomat condos. In September 2018, St. Michael and All Angels Episcopal Church unveiled their second set of plans for their Frederick Square block— a project Miller has also been fighting since 2016 and continues to oppose.

A flawed Preston Road and Northwest Highway Area Plan that was expected to die on a shelf was suddenly pressed into service and seized upon by Miller as (selective) holy writ.

Remember the consultants’ recommendations for Preston Center? Increased residential, lessening office, more vibrancy? Compare that list to Miller’s protests: Highland House residential high-rise, Transwestern’s Laurel apartment building, and the skybridge to Tom Thumb. At every turn, Miller was protesting the very projects Preston Center was judged to need in order to revitalize itself.

Miller is currently fighting St. Michael’s latest combination of residential and office project with community open space. In truth, I’m not a fan of the project either, but not because of the components—I just don’t care for the buildings’ placement and the large above-ground parking garage.

The church owns the whole block, but only the western end near the Tollway is within the zoning district that allows for significant height and density. The eastern Douglas Avenue end of the block is zoned for three-story residential. The church wants to spread those high-density rights across the block—no increase in total square footage, but height would be extended to the whole lot. And what could be 100 percent office space built by-right contains two buildings: one for office and one for high-rise apartments. There would be a significant green setback from Douglas and space for community events and a farmer’s market.

When the plan was announced, the press release contained eight—eight!—mentions of the Preston Center and Northwest Highway Area Plan. And yet Miller is opposed.

Kline said he was for the project.

“St. Michael’s bent over backwards,” he said, adding that he hoped it would be an example to other developments. His only wish is that the project “was in the middle of Preston Center rather than the periphery.” Continuing, Kline said Miller had tried to get the former area plan task force members to all come out against St. Michael’s but only two – Betsy del Monte and herself – wound up opposing the plan.

Miller’s Tactics

Being a former politician, Miller knows how to craft a cult of personality including other former politicians. Easily impressed community residents grab their smelling salts because the former mayor of Dallas is speaking with them. She also knows that people who want to believe something will believe anything that reinforces that belief without question.

Her editorial in the News trades on the same tropes she’s honed in recent years to oppose every development around Preston Center.

She opens with citing “traffic gridlock, zero pedestrian amenities, a shortage of parking.” We all want to believe this is true, but it’s not.

Kimley-Horn reported to the Preston Road and Northwest Highway Task Force that multiple traffic studies going back nearly 20 years showed that traffic on both Northwest Highway and Preston Road has been decreasing overall (yes, it vacillates year to year but the overall trend is down). In a meeting with the a Pink Wall zoning committee earlier this year, the Texas Department of Transportation reported that traffic continues to decrease at Preston Road and Northwest Highway.

Preston Center parking was similarly shown by Kimley-Horn to only be an issue between noon and 1 p.m. on weekdays. They employed car counters to track patterns throughout multiple days. And even at lunch, parking was only 85 percent full. At evenings and weekends, it’s a concrete desert.

Pedestrian amenities were never built and little space exists for them. Preston Center goes from road to sidewalk to building with little break. If pedestrian amenities are such a hot button, why isn’t St. Michael’s being praised for their efforts to bring green space to an area that desperately needs it? One of Miller’s thoughts is to shrink Northwest Highway and build a multi-billion dollar underground tunnel connecting the Tollway and Central. What are the chances of that?

Within the Pink Wall zoning district, Miller claims that developers want to “demolish four low-rise condo complexes and replace them with rental-apartment towers as high as 25 stories.” I’ve been in a hell of a lot more meetings than Miller and can confidently say no plans exist to demolish the four low-rises and replace them with towers. One isn’t for sale, another doesn’t appear to be under contract, another is asking for seven stories, and the fourth, the burned Preston Place, has only shown an amorphous blob eerily similar to the Centrum in Oak Lawn that wants to go tall on a portion of its site (much smaller than shown, in my opinion).

Miller continues, “Hal Anderson, who designed and developed the iconic Pink Wall community 60 years ago — one of the last fully owner-occupied, tree-lined, condo communities in Dallas — would be heartbroken.”

Ludicrous. Hal Anderson’s original plan for Preston Tower was to build a second 29-story tower sideways on the Preston Place lot. His plans for the 21-story Athena originally called for 40 stories. The only thing Hal Anderson would be heartbroken about is that it took so long to reach the potential he foresaw, but that the economics of his time wouldn’t allow.

Miller wants us to further believe she has 78 percent support from Pink Wall residents. She doesn’t. First, no vote has been taken to understand what residents feel. Secondly, her 78 percent is tied to Preston Tower and the Athena, which have similarly not asked their residents’ opinions. Instead, their HOA rules allow their board to cast a single vote for everyone without consultation.

The only link to understanding area sympathies are the responses the city received to Transwestern’s Laurel two blocks away, “242 surveys sent, 165 were returned and of those 96-percent were in favor of the development with just seven dissents.” Vastly different than Miller’s unquantified claim of 78 percent dissent.

I could go on and on, point by point, but I think the picture is clear.

Miller ends her editorial by saying, “We all want Preston Center to be redeveloped.” Given her history of unending opposition to every project in recent memory, that statement is worth questioning.