The author Richard Rothstein, speaking to a group of a few dozen law students at UNT Dallas’ downtown campus on Thursday afternoon, argued that this country’s urban housing crisis is the intended result of decades of government policies that fueled segregation. These policies—the major ones included segregated public housing and a government-funded initiative that incentivized white flight to the suburbs—were more insidious than the segregation of colleges and water fountains, the things that led to the Civil Rights period. These housing policies, Rothstein argued, left entire races of people economically disadvantaged, to the point where, today, black families’ wealth is 10 percent of their white counterparts.

“This is entirely attributable to federal housing policy,” he said. “This determines the structure of this country today.”

Last year, Rothstein released The Color of Law, which goes into far greater detail in arguing that this country’s housing and wealth inequalities were not created by private decisions from banks and developers and homeowners, as has been parroted by institutions as high as the Supreme Court. His book is a roadmap to the federal decisions that got us to this point. Housing projects were segregated from the beginning. New Deal-era facilities were federally designated for whites only and blacks only, serving folks who had steady jobs during the Depression but nowhere to live. They even had to have decent furniture to be approved to live here; the projects were originally for workers. Previously, there were integrated neighborhoods located near a port or a rail system, necessary because few of the workers had cars.

The Works Progress Administration destroyed much of this integrated housing, instead favoring the projects. During the lead-up to the war, new plants and factories were built where there previously was nothing. More segregated projects went up near them. Cities in California wanted blacks to leave after the war, so their developments were poor and shoddy re-dos of where the Japanese lived before they were hauled off to internment camps. Segregation was literally written into the legislation that created these housing projects, Rothstein said. After the war, amid a huge housing shortage, the government began subsidizing single-family, suburban homes. It was often cheaper to buy these than rent in the projects, but only whites were allowed to participate in the program. They fled the projects in favor of owning homes—this created a huge wealth and opportunity gap between the races that remains today.

During his speech, Rothstein said his goal was to get the country to face this ugly history and understand what led to the inequality.

“It was a systematic policy … with explicit intent to segregate every metropolitan area in this country so that black and white people could not live together,” Rothstein said.

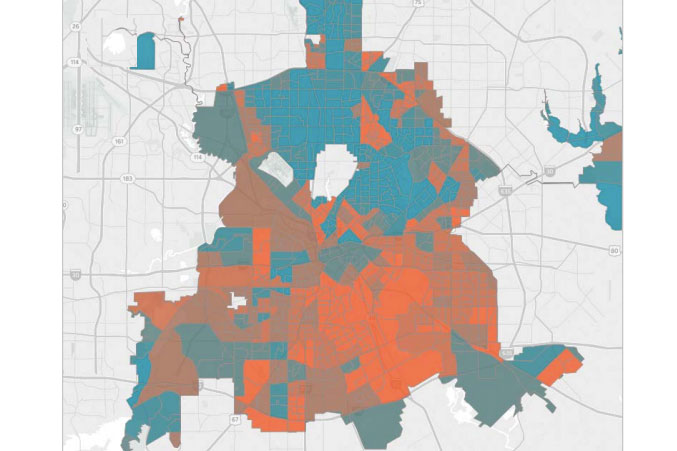

That includes Dallas. Look at the maps.

Last year, you’ll recall Mike Koprowski, the founder and former CEO of the nonprofit Opportunity Dallas, stand up and tell the City Council that segregation was “ground zero in the fight against poverty.” It informs economic opportunity, health outcomes, school attendance, interaction with the criminal justice system. The city has begun to take steps to address this. It ordered what’s called a Market Value Analysis, which identified areas of deeply concentrated poverty as well as those that would benefit from additional affordable housing units. It puts in mechanisms to freeze property taxes and protect against displacement due to a rush of development. The policy is meant to guide the city’s hand in where it chooses to incentivize housing developments, to protect against further concentrating poverty.

“When we finally deal with the issue of housing segregation patterns, that’s when things begin to change,” Rothstein said.

The housing policy is the city’s first, a document that puts some power back into the council’s hand regarding Dallas’ shortage of affordable units in better parts of town. But there are federal policies that are outside the city’s hand. Like housing vouchers. In 2008, the housing advocacy nonprofit Inclusive Communities sued the U.S Department of Housing and Urban Development over its voucher program, arguing that, in setting a flat value for the voucher, the government was further concentrating poor people in Dallas. HUD settled that case in 2011 and was court-ordered to try something different—base the value of the vouchers on ZIP code.

According to Inclusive Communities, voucher holders in what were deemed high-opportunity neighborhoods—lower crime rate, better schools, more available services—tripled. A similar rule was rolled out in 24 other areas in 2016, based off the results in Dallas.

Rothstein argued that fixing these problems isn’t difficult. Policies like the ones mentioned above would go a long way in giving poor people the opportunity to find affordable housing in better parts of town. What’s missing is the political will to do so.

“What was created by government policy can be undone by government policy,” he said.

He suggested only giving the federal Mortgage Interest Deduction to homeowners who buy in a community that is not segregated. If the federal government was really serious about remedying this problem, it could buy back homes at market rates and sell them to black families for what white families bought them for after the war. (In today’s dollars, that would come out to around $100,000, he said.) And then there is the Low Income Housing Tax Credit, or LIHTC, which is used to incentivize developers to build affordable units. “You know this better than anyone here in Dallas,” Rothstein quipped.

It brings us back to the city’s housing policy. Rothstein’s remedy here lined up exactly with the goals of the policy, which are to use data to identify neighborhoods that are near jobs and services and good schools and could benefit from a little mix in their housing stock. Then get units built there. Some on the council are already trying to amend the policy, which would help people who are currently suffering in dilapidated complexes but would do little to change the long-term problem of concentrated poverty. There is also the matter of the landlords who accept housing vouchers here. Dallas County, after all, is where a lawsuit has been filed that challenges state legislation that blocks cities from mandating that landlords accept vouchers if the individual can pay the rent. If anything, it only shows how deeply entrenched segregation remains in these programs—the lawsuit says that 86 percent of voucher recipients in Dallas County are black.

“What’s hard is developing the will to change and developing the understanding of this history,” Rothstein noted.

It’s playing out all around us.