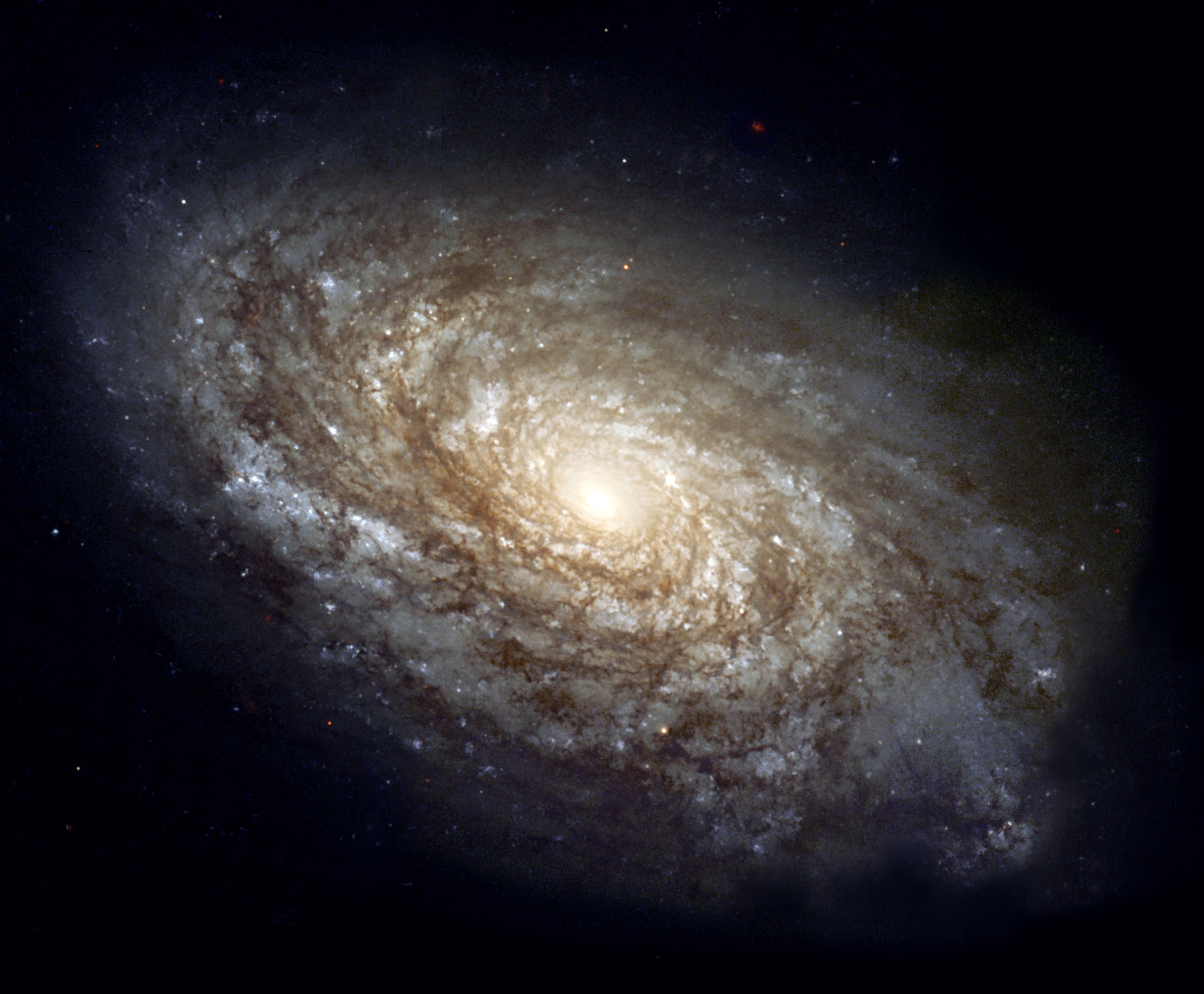

A simple concept of astronomy has always boggled my mind. Because of the rate of speed by which light moves through space, the illuminated stars we see when we look up at the sky at night are the images of stars as they existed millions of years ago. The light is old; we are looking through time.

I thought of this astronomical phenomenon while reading this article in the Dallas Morning News about a highway fight unfolding on the outer fringes of our metropolitan galaxy. Collin County and TxDOT are planning new roads to keep up with massive growth. Residents are worried the new roads will cut through and destroy their neighborhoods, ruin the value of their homes, and damage their communities. It is like the growing pains of 1960s Dallas are unfolding in Collin County in 2018. The debate is old, reading about it feels like peering through time.

The players involved are repeating the same old refrains. Demographers looking through their statistical telescopes expect Collin County to double in population by 2030, outpacing Dallas County’s population by 2050. Public officials—both the data crunchers at TxDOT and the dutiful elected servants of the county—believe that this problem needs to be addressed by making more room, not for the expected arrival of people, but for their cars.

“Congestion on the county’s major roadways will only get worse,” the DMN reports.

“[Michael Quint, executive director of development services for McKinney] said Collin County is “definitely behind the eight ball” in its number of highways compared to where Dallas and Tarrant counties were when they were of similar size.”

“’It just happened so fast and so unexpectedly that we weren’t able to catch up. But I think we’re doing better jobs of that now,’ [Quint] said, adding that finding a solution to U.S. 380 is just one step. The county needs to build out its arterial network, he said, and that means “smarter” and “more refined” traffic management.”

To build out that “smart” and “more refined” traffic management system, which fundamentally resembles every dumb traffic management system that has been rolled out across America over the past 70 years, Collin County commissioners are going to ask residents to approve a $671 million transportation bond this November. Eighty percent of the funding would go towards building new highways where it is “expected to see a lot of population growth.” Twenty percent of the funds would go to improve thoroughfares and city arteries “that help feed traffic onto highways.”

In other words, people are coming, so we must build lots of new roads. The debate currently hinges on fears over how this will affect the future of Collin County. But there is an advantage of looking back in time: you know how the future will turn out.

This is what will happen: Federal, state, and local governments will subsidize a massive expansion of highway and auto-centric infrastructure as a singular solution to deal with their expected growth. The new infrastructure will, in turn, determine where that growth occurs. The majority of new development will be low density, single-family homes and subdivisions, with office towers and parks, strip centers and big box stores to service employment and consumer needs. Investors will be driven by new or widened roads towards undeveloped land—the cheapest land—placing new growth where it doesn’t exist today, thus putting pressure on the further expansion of the highway infrastructure.

The massive expenditure of public funds on infrastructure will function as a subsidy and incentive for this low-density development, and yet, the low density will not be able to generate sufficient new taxes to deal with the maintenance, upkeep, and continued expansion of auto infrastructure. But those costs won’t be realized for decades. In the short term, there will be reduced congestion, and the public officials—from the politicians to the TxDOT engineers—will appear to have successfully navigated the challenges of the future. But they will fail to see that congestion is like a rash, a symptom of a deeper problem that is more difficult to diagnose and treat.

The real problem is a cyclical pattern of development that we have seen transpire over and over throughout the past 70 or so years in DFW. The transportation infrastructure doesn’t treat the challenge of congestion, rather, it establishes the economic conditions to generate further growth that will only place continual new pressure on roadway capacity. Congestion will only get worse again. That is because there will be one singular defining characteristic of this new growth cycle: all those new people—the millions whom officials believe will help Collin County grow larger than Dallas County—will have to drive cars to survive in the new world their public officials plan to build.

There are some Collin County residents who are unhappy with this strategy for the future. They have packed public meetings; they have spoken of their fears that new highway construction will divide their neighborhoods or destroy the value of their homes. Some believed, like long ago residents of Preston Hollow, Bent Tree, Richardson, or parts of Plano before them, that they purchased homes on the rural fringes of the region believing they had secured a piece of country heaven with easy access to the benefits of city living. Now they are being told that a tsunami of concrete is on its way, and they must either prepare for it or be plowed under by the sea of sprawl.

Reading about their concerns, I’m reminded of that scene at the end of A Christmas Carol when Scrooge throws himself at the feet of the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come and pleads for a reprieve from his sorry fate.

“Before I draw nearer to that stone to which you point,” Scrooge says, “answer me one question. Are these the shadows of the things that Will be, or are they shadows of things that May be, only?”

Sitting here at the center of the metropolitan galaxy, looking out from the future and back into the past, I feel like I can offer the residents of Collin County little more than the ghost could offer Scrooge. Must these things be? Is the fate of their homes and communities inevitable? Will it all succumb under the tsunami of sprawl?

Of course, Collin County does not need to spend nearly three-quarters of $1 billion to build new highways and expand existing roadway infrastructure. In fact, the last 70 years of urban growth have demonstrated clearly that this is a fool’s errand, a Sisyphean task born of short-term, misguided thinking based on unsound ideological and unproven pseudoscientific thinking that has only destroyed communities as we once knew them, while kicked the challenges of urbanization down the road to subsequent generations.

Dallas did this, doubling down in its investments in highways to facilitate and speed up the spread of a monolithic vision of sprawling growth across the open blackland prairie of North Texas. Dallas’ solution to projected growth was to devise ways that allowed the growth to bypass Dallas for newer and newer developments built in the pastures of the north, a strategy that placed an ever-increasing pressure to further expand infrastructure while allowing its own tax base to erode.

The inner-ring suburbs bought into the same mindset, and their decades of rapid success were plowed under as the concrete tsunami continued its surge northwards, dragging with it jobs and taxes. Now they face community challenges similar to those of the historic urban centers.

If the Collin County residents are worried about losing their little slices of country life on the outskirts of the region, they should be. The growth their public officials are attempting to sell them on allows for only one way to live—suburban sprawl.

Which is the great irony in this debate. The leaders of Collin County, a bastion of conservative power, are attempting to sell their constituents on a vision of future growth that uses vast amounts of public funding to subsidize a form of growth that vastly limits choice in the marketplace.

Furthermore, it is happening in a corner of the region that has already seen the benefits of what reintroducing housing and community choice—things like restoring historic downtowns, strategically reintroducing density to lure younger residents and decrease dependence on cars—can do for suburban communities. Places like Legacy in Plano and downtown McKinney show the potential of a new kind of suburban growth, which is really the oldest kind of growth: clusters of density at town centers, with decreasing density as you move away from the town center towards lower-density suburban-style neighborhoods and semi-rural fringes.

This is a possible vision for Collin County’s future. It is the kind of growth that would absorb those expected millions of new residents without putting the same pressure on building and expanding roadways. But it would require a radically different way of thinking—a complete reversal of how everything has been done. It would require thinking about how to incubate urban clusters in suburban communities, how to allow more residents to get out of their cars, how to invest in public infrastructure designed for people, and not for the cars we presume they want to drive.

Looking out though time and into the past, I feel a little bit like Scrooge’s ghost. I can’t say whether things Will or May be. All I can do is point to a quote in that DMN story that stands like Scrooge’s tombstone in the cemetery, a reminder that if things don’t radically change—if people and politicians don’t take power and ownership over the fate of their own communities instead of continuing to continuing to do business as usual and defer to false ideology and singular-minded logic of highway engineers—there is only one possible future. Behold, the quote:

“Ultimately,” Quint said, “we will support whatever TxDOT comes down with.”