Last week we got a look at a schematic study that the Texas Department of Transportation created for the planned renovation of Interstate 30. What was frustrating about the draft was that it seemed to fly in the face of TxDOT’s own acclaimed CityMAP study, which is supposed to guide the planning process around I-30 and Dallas’ other inner-city freeways. Instead, it seems to be gathering dust on a shelf somewhere at Dallas City Hall.

TxDOT’s preliminary engineering plans for a rebuilt I-30 differ from the design possibilities laid out in CityMAP. Most succinctly, TxDOT’s design is a bigger road. CityMAP’s two downtown options (the third option reroutes I-30 around South Dallas) include either four lanes of traffic each way with two center “managed lanes” or five lanes of traffic each way with two managed lanes. The new TxDOT schematic appears to depict six lanes of traffic each way, with two managed lanes, and it also adds additional frontage road capacity along the freeway.

Frontage roads and widened highways will depress the property value and development potential along this critical stretch of inner-city neighborhoods. An increase of infrastructure will only serve to further divide downtown from neighborhoods to the south.

Forget all that, though. More important: historical traffic data for trips along I-30 show that the freeway does not need to be widened.

TxDOT publishes historical traffic count information on its website. Looking at the three main sections that will be involved in the I-30 redo—the portion through downtown into the Cedars onto Fair Park and all the way to Munger—all show flat-lined, fluctuating, or decreasing amounts of traffic. However, in all three sections, TxDOT’s available traffic projections anticipate large increases in traffic, anywhere from 30 to 63 percent. Recent traffic trends show no evidence that these kinds of traffic increases are reasonable. If anything, recent traffic trends show that there is no real need for increased capacity along I-30 in downtown Dallas.

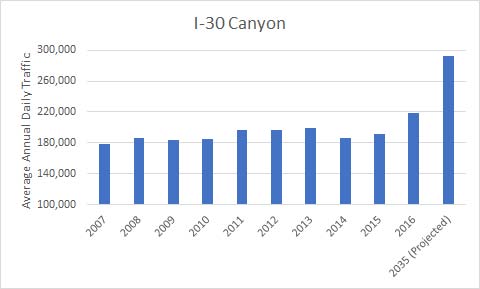

I-30 Downtown Canyon

Traffic through downtown Dallas on I-30 has remained relatively constant over the past decade. Between 2007 and 2015 there was only a 7 percent increase in vehicles passing through this portion, which is known as the Canyon. Nonetheless, TxDOT anticipates that there will be a 63 percent increase in traffic over 2007 levels by 2035.

There was only one sharp increase of year-over-year traffic in this part of I-30, which saw a 14 percent jump between 2015 and 2016. Here’s one hypothesis: by 2016, construction was finishing up on the massive Horseshoe Project. The 2016 increase in traffic appears to be a textbook case of induced demand. As more capacity was added to the I-30/I-35 interchange, there was an increase of traffic on I-30.

If this is the case, it helps illustrate a disconnect between the way highway engineers and neighborhood advocates understand traffic capacity. I-30’s stabilized traffic numbers indicate that the current road has hit capacity with regards to the number of cars it will carry. For an engineer, this situation should be addressed by adding additional lanes for capacity, which will increase the number of cars carried by the corridor. But these numbers also indicate that when capacity is increased, the problem of congestion is not solved. Even though more cars are moving through I-30 today, the road is still jammed.

This is why neighborhood advocates are more concerned with how this endless struggle to increase capacity impacts the areas through which highways carry traffic. The CityMAP study attempts to balance the demands of transportation with the costs of transportation on the value and quality of life of the neighborhoods around highways.

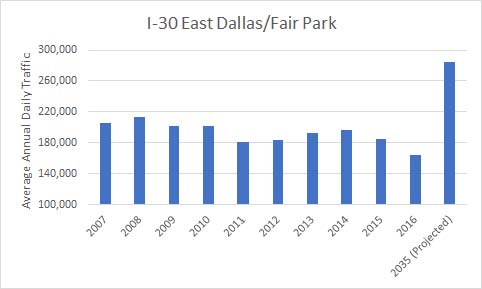

I-30 East Dallas/Fair Park

The stretch of I-30 east of downtown tells a different story. Here, traffic has been declining over the last decade. Between 2007 and 2016, traffic along this stretch dropped 11 percent. The largest year-over-year increase occurred in 2013, but even then traffic only increased by 5 percent, or about 9,000 vehicles per day. Nevertheless, TxDOT projects that by 2035, traffic will increase to a level that is 73 percent greater than the average daily traffic counts in 2016. Here induced demand doesn’t seem to explain the situation. TxDOT is building for future drivers that evidence suggests will never exist.

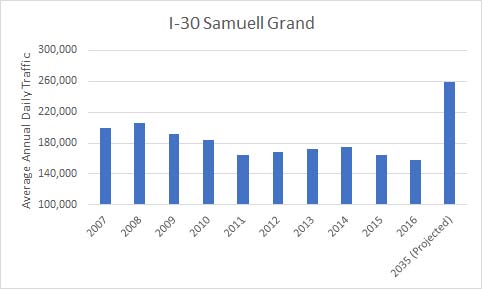

I-30 Samuell Grand Park

The TxDOT schematics also show a widening plan that, again, is not justified by historic traffic numbers along I-30 in the Samuell Grand area. Between 2007 and 2016, traffic on this section of I-30 has decreased by 21 percent. And yet, once again, TxDOT anticipates a 65 percent increase in traffic over 2016 levels by 2035.

One major way the schematic drawings sent to Dallas City Hall by TxDOT differed from CityMAP is that they plan for I-30 to come up from its below-grade alignment around Samuell Grand Park. CityMAP envisions a below-grade I-30 continuing past the park in order to stitch back together the East and South Dallas neighborhoods that were ravaged when I-30 was first constructed. The freeway is an elevated barrier that has long played a major factor in the continuing economic, social, and racial segregation of Dallas.

There are drainage issues in that part of Dallas that may make a below-grade I-30 more costly than previously thought. But what is ultimately greater? The extra cost of sinking the highway or the opportunity cost of missing a chance to bury one of the most significant contributors to the division and disinvestment of part of the city? It would behoove Dallas officials to at least study what it would take to put that portion of the freeway below ground.

Here are the data sets.