The Trinity River Project, as an art exhibition, is moving downstream to the Galveston Art Center this month, and Sunday is Earth Day. It’s an opportune time to discuss the Trinity River as a complete ecosystem and its connection to sea-level rise. The river, often portrayed in city literature in abbreviated form and filled with blue water, is actually 710 miles long. The water is not really blue, and will never be blue, because it carries a heavy sediment load of sand, silt, and clay on its way to the sea. Once in coastal waters, the sediment plays an important function in an ancient and complex redistribution system. As one example, accretion of Trinity sediments contributed to the formation of Galveston Island some 6,000 years ago.

The Trinity River Project — a collaborative initiative that is part journalism, guided meditation, and art exhibition — launched in Dallas in 2016. The project will be one of three water-centric exhibitions to open at the Galveston Art Center on April 21. GAC director Dennis Nance says he began thinking of the shows as a trilogy soon after gallerist Liliana Bloch contacted him about bringing the Trinity River Project to Galveston. From there, he worked “to pair the exhibition with other work by artists who in some way respond to the environment from different approaches.”

In the main gallery, visitors will encounter an exhibition titled “Stratiforms,” which includes work by artists Robin Dru Germany, Jason Makepeace, and Page Piland. Nance says, “Germany’s photographs portray waterways from the Panhandle to the Gulf Coast; Makepeace uses whole logs to excavate miniature kayaks and oars; and Piland uses sections of reclaimed wood to create trompe l’oeil paintings, with a few of these works taking on the shape of kayaks.”

In the second-floor gallery, adjacent to the Trinity River Project, Chance Dunlap will display his handmade fishing lures. The artist is also creating a “swap wall” for visitors to have the opportunity to trade their own lures, which, according to Nance, “is a common practice at trade shows for fishing lure enthusiasts.”

In short, the three exhibitions opening this Saturday in Galveston will offer a variety of artistic entry points for contemplating how humans engage with nature and natural processes. It’s all part of the plan, GAC’s director says. “My hope is that these three shows bring some awareness to the importance of water and how we interact with it.”

The Coastal Trinity

In 2016, when the Trinity River Project launched, 10 essays appeared on this blog over a period of two weeks. The essays concentrated mostly on the upper basin of the Trinity River, in Dallas County. With the project moving downstream to Galveston, it made sense to reach out to coastal experts to find out more about what goes on at the mouth of the river. In the process, I’ve started to grow a new lexicon. A few words and phrases collected thus far include: “ancestral Trinity River incised valley,” “Texas Mud Blanket,” “bayhead delta,” “estuary,” “sedimentation,” and “saltwater wedge.”

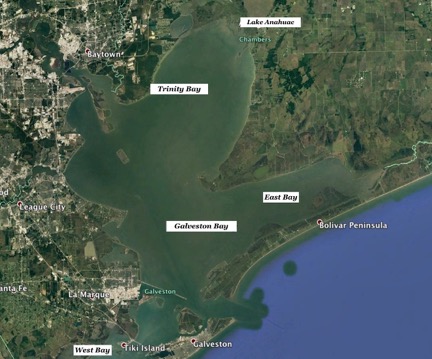

Before we get to what the experts have to say, let’s look at a map of the area. What most people call Galveston Bay is actually four adjacent bays: Galveston, Trinity, West, and East. It’s less confusing (and more scientifically accurate) to refer to the area as the Galveston Bay Complex. The complex looks like this:

Bays, Estuaries, Sediment

Dr. James Westgate, geologist and professor at Lamar University, had this to say when asked about the importance of the Trinity River at its southernmost reaches: “The Trinity River is the lifeblood of the Galveston estuary. It pretty much supports the oyster crop and giant nurseries. Anything we catch in the sea has spent time in estuaries. Without them there is no [seafood] industry.”

An estuary is a place where freshwater and saltwater mix in varying ratios. It is a fecund environment that supports extensive biotic communities — if the ratio doesn’t become skewed due to either an influx of freshwater or a lack of it brought on by drought conditions.

Over the course of an hour, Westgate explained the forces that have shaped today’s estuaries in the Galveston Bay Complex. The complex was once an active river valley incised by the Trinity River. Twenty thousands years ago, the beach was 150 miles offshore from present day, and the valley stood 400 feet above sea level. Seven thousand years ago, sea levels began to rise as ice caps and glaciers melted. As a result, the Trinity River incised valley was “drowned.” The drowned river valley is now known as the Galveston Bay Complex.

The estuaries, he says, are nurseries for oysters, blue crab, brown shrimp,

black drum, redfish, and seatrout (to name a few). For some species, the adult will migrate back and forth from the estuary to the sea. Others are born in the estuary but never return to brackish water as adults.

There are several factors that contribute to the productive growth cycle in estuaries. For one, Westgate says, they provide cover from predation and a steady supply of nutrients. The Trinity River contributes in large measure to these conditions.

Upstream, the Trinity River is able to maintain suspended solids based on gradient and speed of flow. But when the river hits sea level and encounters tidal flows, it loses the ability to hold sediment, and it drops to the bottom. The settled-out sediment is beneficial in several ways. Most of the cover in the estuary is “marsh vegetation or submerged aquatic vegetation (SAV),” according to Westgate, and “the sediment provides a place for plants to anchor their roots.” In addition, the sediment provides “inorganic nutrients as it chemically breaks down.”

The deposition of sediment that fosters thriving nurseries also gums up the works of human-driven enterprise. A navigation channel that crosses the Galveston Bay Complex and connects with the Houston Ship Channel by way of the San Jacinto River must be constantly dredged to a 45-foot depth to ensure large tankers and cargo ships have necessary draft. The dredged material, Westgate says, is often put on top of wetlands, and impounded behind levees, instead of deposited on dry land. There are efforts underway, however, to create an acre of wetland elsewhere for every acre used as a dumping ground.

Sediment relocation is a big deal in and around the Galveston Bay Complex for many reasons (see here). To catch a glimpse of the importance of “regional sediment management” for the human economy, see the photograph below. Sediment-laden water is guided directly into the Gulf by an engineered feature called the Texas City Dike (it’s the thin white line pointed toward the channel between Galveston Island and Bolivar Peninsula). The dike guides sediment out to sea and also prevents it from entering Galveston’s port area, located in West Bay.

Sediment and Sea-Level Rise

Removing sediment from a natural system, or throttling its supply by way of dams and reservoirs, has consequences, especially when taken together with an accelerated rate of sea-level rise. According to Dr. John Anderson, a geologist, academic, and author of The Formation and Future of the Upper Texas Coast, “sea-level rise is balanced by sediment supply, which has been reduced in historical time due to construction of Lake Livingston.” Lake Livingston, an in-channel reservoir situated on the lower Trinity River, provides municipal water supply to Houston. But damming the river limits the amount of sand, silt, and clay making its way to the delta.

The Trinity bayhead delta, Anderson says, is “a significant ecosystem within the river-bay complex.” The delta was expanding during the slow relative sea-level rise of the past few thousand years, but he says it began to shrink in recent decades. “So, the delta is threatened, which means that, if it responds the way it has in the past, it will shift landward.”

While he is not aware of any studies that have focused on historical sediment supply to the delta, he says what is needed “is an assessment of rates of sediment supply needed to counter the acceleration of sea-level rise.”

Epilogue: Where Are We Going?

The study of sea-level rise — and what coastal communities here and around the world may be able to do in advance of its catastrophic consequences — is a deep subject. The first step toward mitigation is acknowledging the consensual science on what is causing the sea to rise at a rapid rate, coupled with a willingness to examine interrelated systems — such as the relationship between rivers and deltas; freshwater and seawater; sediment loss and sea-level rise.

Clearly it’s not possible to fix what ails the planet in a day. But it is possible on Earth Day 2018 to imagine that the concerns of artists and those of the scientific community might share some overlap. According to Nance, environmental issues are important to include in the GAC’s programming because: “Galveston is a witness to one of Texas’ most valuable natural resources, the Gulf Coast. This coastal community is distinctly impacted and uniquely vulnerable to environmental changes.” He grew up in Houston, and whatever the risks, he’s always loved living in proximity to the ocean. “The horizon line from the coast has always been a very important thing for me. It reminds me of how small we are as individuals, in a calming sort of way.”