Ricardo Paniagua is best known to the Dallas public for outdoor artworks that brighten the West Village. The first, his “Super Deluxe” mural, was unveiled at the shopping center in November 2016. Almost instantly it became one of the most Instagrammed street-art spots in the metropolis. It was splayed across West Village brochures like a new logo. “Super Deluxe” satiates a formerly drab garage wall with an grid of colourful rhombi that, by means of a classic optical illusion, transform into rows and rows of stereographic cubes. Only a block away, at the intersection of McKinney and Lemmon, he installed a thermoplastic crosswalk of painted partitions in exuberant yellow, blue, and green. The title: “Unicorn Art Theory.”

Though he’s cast himself as a provocateur—an online troll in a hat bearing the words “ART GOD,” a self-described “Lindsay Lohan of the Dallas arts scene” who rejects attempts to contextualize his work with the gentrification ongoing just outside his West Dallas studio—Paniagua’s success is a product of no mere daring. His fierce dedication to art, having emerged spontaneously when he was just a teenager, has since become his “method and medium of navigating the world.”

He’s been steadily selling paintings through the Bivins Gallery in the Crescent Hotel, frequently visiting the homes of buyers and posting images on social media of the installed work. “One day I want to collaborate with IKEA to make some of my geometric sculptures small and cheap, so kids can have them in their room, play with them, keep them, break them,” he says. For this conversation, Paniagua stepped away from what will be his largest painting on canvas, at 15 feet tall by 11 feet wide. The exchange has been edited for length and clarity.

How has your self-image as an artist changed over the course of your career?

I don’t think it has changed at all. (laughs) You know, I came into the art world off the street. I dropped out of high school, so I didn’t know anything about that culture. I didn’t even know an artist can have their artwork exhibited while they’re still alive; that’s how ignorant and naive I was. You go to school, and they have student exhibitions at the university … I don’t think my image has changed; I think that my perception may have changed because I actually became successful.

When did your interest in tessellation and optical illusions begin?

When I was going through puberty, I started developing some OCD-related characteristics with numbers, and what I found about art is that art makes me exercise the anxiety out of my mind, and it would bring me therapeutic results.

Were you looking at other artists’ work when you were discovering all this?

No, I was still homeless at that point. I was shown some geometric art in my dreams, and so I got up and started making it. And that’s when all that started happening.

How do you choose the media?

I think actually that media just exists in my path, like universe is conspiring for some artwork to be made. So I just find it. In some strange way I feel compelled to get that material for the current project, or the next project, so I pick it up and keep it until the time comes to use it. The material itself does not inspire me; it is intuition that maybe I need this, and maybe it will sit in my studio for years until I use it. It just works its way into my life.

Like the chunks of wood painted with colourful stripes?

Oh, the trees! I love them. Those are called “Glitch” paintings. For me, they are a conversation about nature and technology.

Do you use technology to make art?

No, I don’t know how to use computers that well. I know how to use them, but not that well. Some people have thought in the past that I use computers, but really all I have is my brain.

Do you prefer traditional media then?

I have an open mind, but it’s not about what I want or what I like. It’s about what art wants to exist in the world.

Can we talk about the public art that you’ve made, what were the challenges and rewards there?

Throughout my career, or in the early part of my career, I never wanted to do public art. Especially in Dallas. The city’s Office of Cultural Affairs has all the money for public art, but they they also have a lot of stipulations to proposals. I think that that is the wrong way to have art in the society, in public. They are trying to control art — to control the image of the city with art — and the truth is, you cannot control art. So I never did anything to try to get involved with it even if I had some ideas. And then last year, these people pulled me by the arm to do a public art crosswalk, and I told them, “I don’t want to do it. I only want to make what I want to make, so you have to trust me, or I don’t want to do it, and just don’t call me.” And they said, “No, we trust you, do whatever you want. We trust you.”

So I did it, and then all of a sudden many people, private property owners, are calling me from different cities, and I tell them the same thing, “We don’t need to talk if you want to me to put something you want; if you want to do that, hire a designer.” And people love what I do so far, and it’s snowballing now. Public artwork, on my terms. Because I think I know what is best, and what is best is for art to be free.

Do you think public art is going to be free in Dallas at some point?

For Dallas, I don’t think it will happen until young people start taking over the city seats and positions of power, which may still take some time. If I do something for anyone in Dallas, it’s for a private effort. For instance, West Village is a public area, but it’s private property. It has the developers who can tell me, “We’ll pay you, and you do what you want.” So I like to do public art, but not with the government.

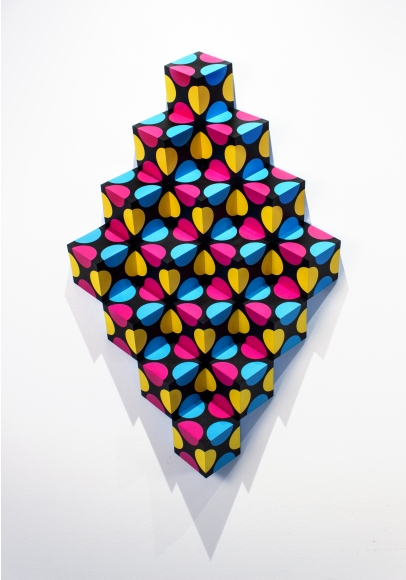

acrylic on cast fiberglass, Urethane resin, 33″ x 22″ x 5.”

It’s not worth getting mixed up in the bureaucracy?

No, not worth it. It makes you too stressed out.

Do you have a favorite audience?

Children. All ages of children, until they start becoming corrupt. In America, people here are kind of mean. Yes, they are dealing with a lot of issues, but the kids — they start becoming negative around the time they’re in high school. I think that art should be a positive experience. So what I’m saying is that most children have open minds still, to engage in beautiful things like artwork, and when they get older they start losing that innocence…

Do you mean that they become cynical?

Yes, cynical. People don’t always realize how to be progressive when they may not even understand what they are experiencing. One of my ideas for artwork, which is mostly true especially with geometric art, is that I want it to be accessible to everybody — which obviously doesn’t happen — but, to all ages. When you have artwork with maybe nudity and distastefulness, a little kid cannot go see that. An artist sees himself in the work, he is free to do anything, but for me personally, I don’t want to alienate children. They are too special.