Many cities around the country have in recent years been reckoning with the toxic effects of racial housing segregation, in part because they had to. A 2015 federal policy required communities to study residential segregation in order to receive billions of dollars in funding. No longer: That requirement has been postponed until at least 2020, Ben Carson’s Department of Housing and Urban Development announced last week, the latest Trump administration move in its campaign to repeal anything and everything possessing even a whiff of the Obama era.

Regardless, Dallas will continue its assessment of housing inequality, Beverly Davis, director of the city’s fair housing and human rights office, writes in an email: “The City of Dallas is making no changes as a result of the HUD announcement regarding the Assessment of Fair Housing (AFH). We are moving forward with the AFH with a goal of implementing a plan that will affirmatively further fair housing and address the housing needs of the community.”

That assessment began about a year ago, with the city of Dallas handing the investigative reins to a team at the University of Texas at Arlington. Researchers at the university are heading up the North Texas Regional Housing Assessment on behalf of the housing authorities at more than a dozen Dallas-Fort Worth area cities.

Myriam Igoufe, project manager of the UT-Arlington assessment, says the regulatory turmoil in Washington won’t halt the progress made here. “The fact that the submission is no longer required does not invalidate or nullify (everything) we have gathered,” Igoufe says. Researchers are in fact continuing to gather information: public meetings are scheduled in Dallas throughout this month and the next, and Igoufe says her team tentatively hopes to be able to present much of its work by June.

And proponents of the now-delayed Obama-era requirement, the “affirmatively furthering fair housing rule” that was intended to, in essence, follow through on the promise of the 1968 Fair Housing Act and encourage desegregation, are already taking aim at HUD’s latest decision. Any legal challenge to HUD, which has said the assessment of fair housing requirements were ineffective and burdensome on communities, would hinge largely on dry questions of procedure. More compellingly, an objection signed by 76 national organizations also accuses the federal government of failing to abide by that 50-year-old law, which outlaws discrimination and requires municipalities to “affirmatively further” equitable housing. (It’s the latter part of that rule that, until 2015, was arguably never enforced at a federal level.)

But Dallas doesn’t need the federal incentive to examine the inequality that keeps many of the city’s residents impoverished. The city is already preparing this year to finally come up with the comprehensive housing policy it has long lacked—preparing to prepare to come up with one, at least—and new nonprofits like Opportunity Dallas are making a convincing case that many of Dallas’ biggest problems are inextricably tied to housing segregation.

Igoufe says that a desire to bring solutions to housing problems is shared regionally, by the 20-plus groups signed on to the North Texas Regional Housing Assessment. “One of the dominant narratives from the very beginning (has been) that we want the information to make a compelling case for policy initiatives,” she says. The round of public meetings being held now is intended mostly to seek public input on strategies to help North Texas desegregate.

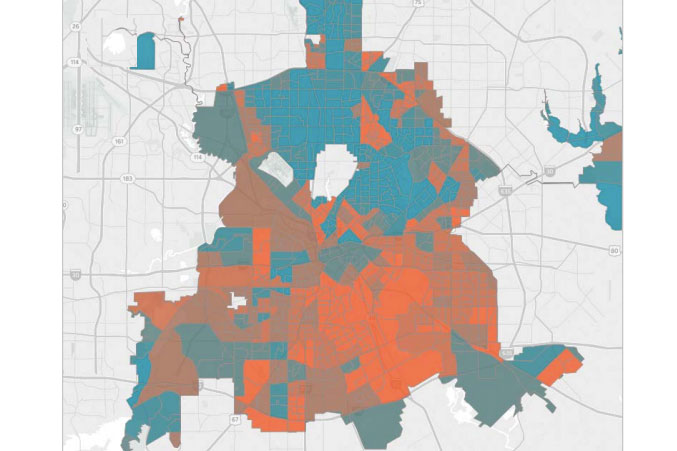

The nature of the housing segregation problem that keeps about 90 percent of Dallas’ impoverished children stranded in roughly half of the city’s census tracts was already understood—isolating communities along racial and economic lines limits opportunity to those who live in wealthier, often whiter neighborhoods. If anything, Igoufe says, researchers have learned that they underestimated the size of the problem, and its compounding effects on everything from economic mobility to transportation. “Looking just from 1990 to 2016, segregation now is getting worse,” Igoufe says. “We don’t see any real improvement. It’s a little alarming, really.”