The Trinity River has been through a lot, never to reach the Gulf of Mexico as a channel for goods. That was the plan in 1892: make the Trinity navigable for ships to travel 700 miles of narrow water path from the center of Dallas, refashioning the city as a point of economic trade. But the river went and flooded in 1908. That complicated things.

Dallas didn’t back down. Officials decided to just move the river. The city hired an urban planner who’d recently designed Fair Park, and ambitions for the Trinity became a new blueprint for the city. George E. Kessler, also a landscape architect, the same one associated with the Kessler neighborhoods in Oak Cliff, would lead an effort to reroute the river into submission, ultimately taking the form of a 26-mile canal.

The Port of Dallas project picked up where the Kessler Plan left off and kept going for the next 55 years. An episode of 99 Percent Invisible tells the story of freeway bridges made tall with the height of sea vessels in mind, of a new DFW airport that nulled any desire for a seaport. The Trinity became a pariah and a receptacle for litter and sewage and shame. Whole ecosystems had shifted at the whims of city officials. The city built itself up around The Port of Dallas. The Port of Dallas never existed, its only legacy a waste of land and money.

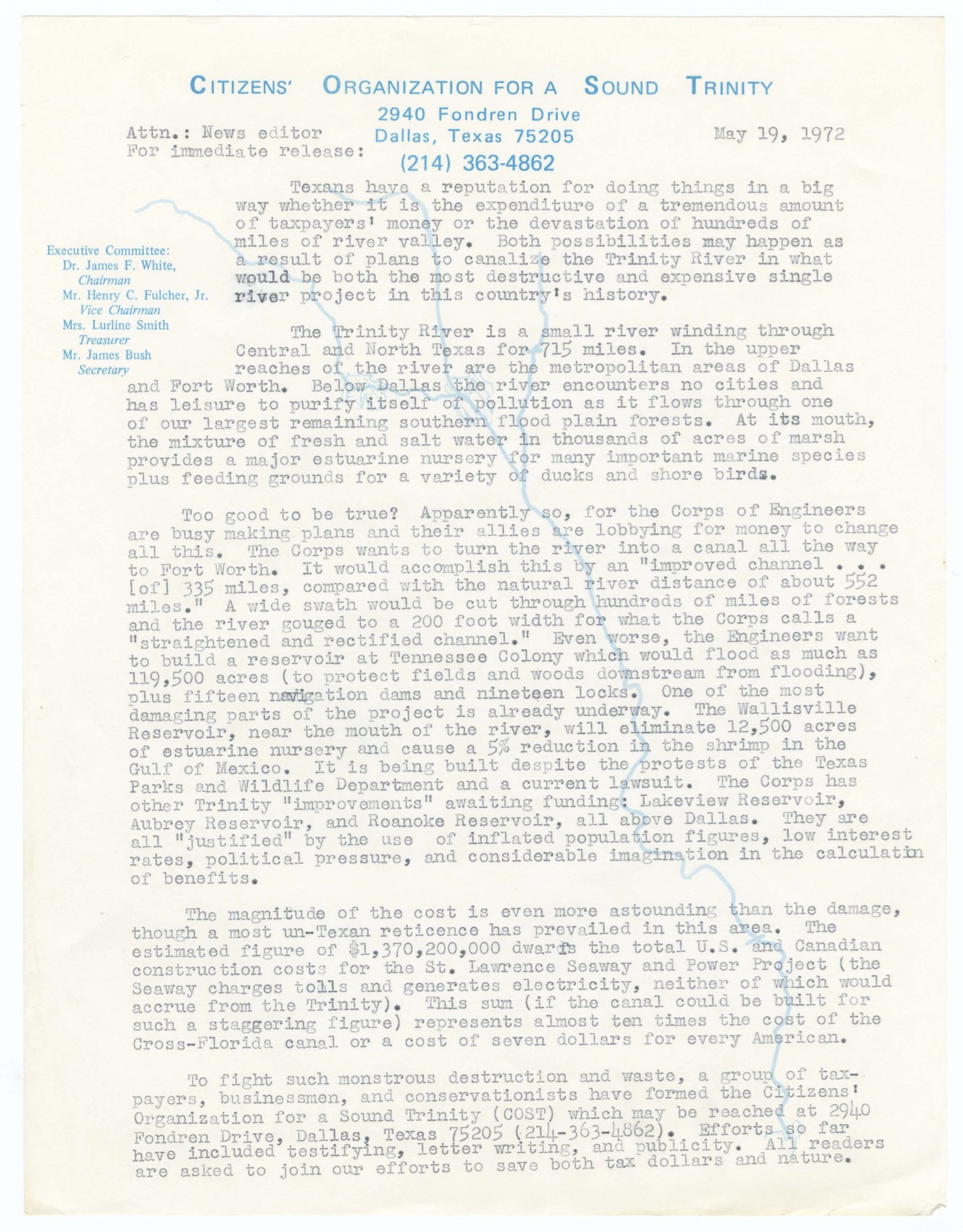

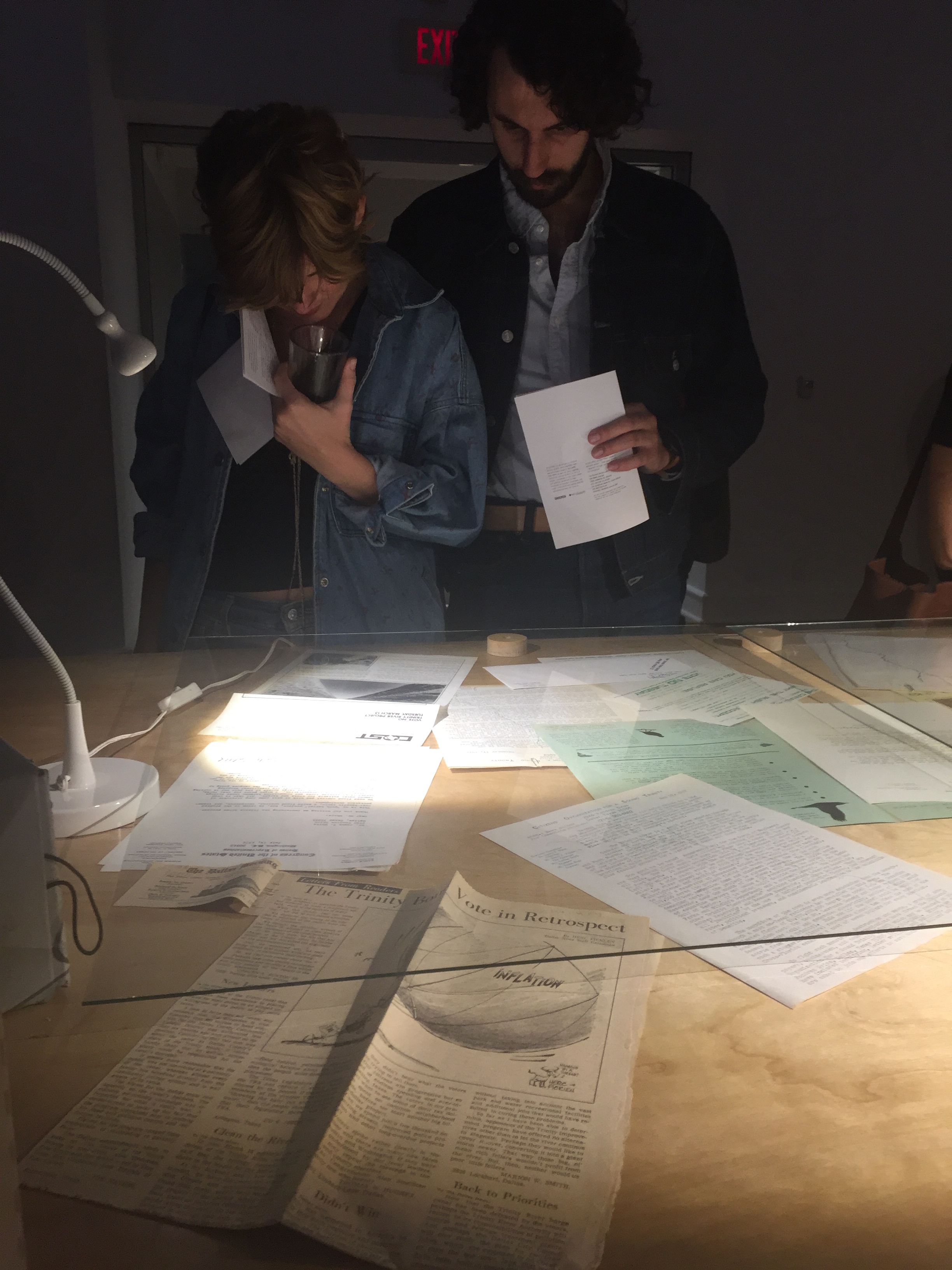

“The history here is not nice, but there’s something here to work with,” says Sofia Bastidas, director of SMU’s Pollock Gallery and co-curator of Wide Open, a new show on through December 2nd. She leans over a narrow, subtly winding suspended table covered in brightly lit evidence of that history — documents, negatives, and archives proving more than a century of concern about Dallas’ suppression of nature — and reaches first for a typewritten letter. The Citizens’ Organization for a Sound Trinity warned in 1972 of the destruction to marine wildlife and forests the Corps of Engineers would do in forcing the river to a 200 foot width. The writer compares an estimated $1,370,200,000 in costs to New York’s St. Lawrence Seaway and Power Project, which was much easier on taxpayers (and actually generated electricity.) “All readers are asked to join our efforts to save both tax dollars and nature,” the final sentence reads.

An image of the Trinity’s route in faded blue on the letterhead cuts underneath the text, diagonally down the page. Next to it, the same river lines traced on blank paper show a study that produced the letterhead. “Use this map” is handwritten at the top.

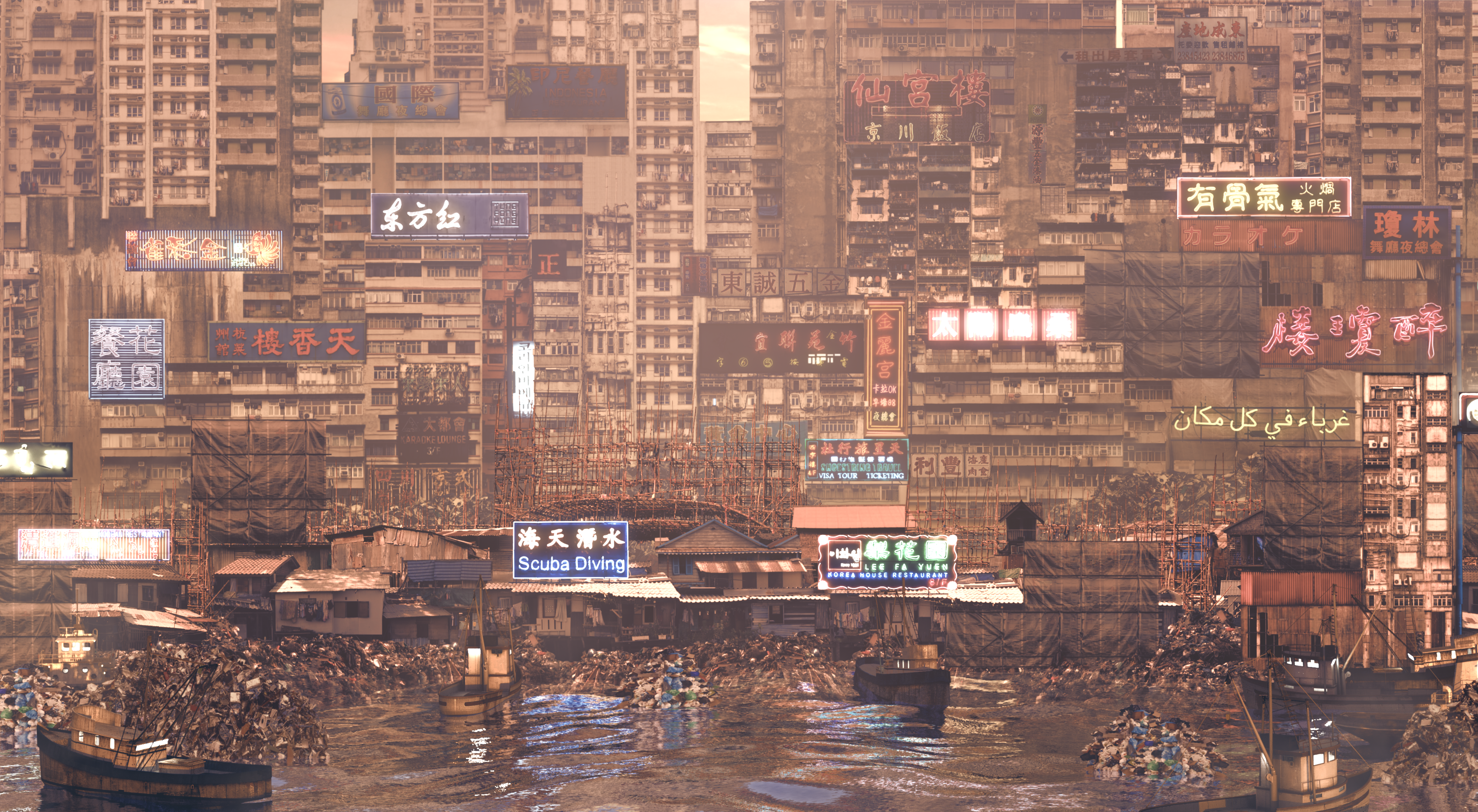

Bastidas and New York-based urbanist Guillermo León Gómez created Wide Open as a research exhibition that could, among other things, ground premature discussions about the Trinity’s potential that imagine utopian greenspaces and art projects with the same revisionist mindset of pro-port planners. The celebration of the Trinity Toll Road’s death, for example, can obscure the millions of taxpayer dollars spent in the lead-up to its demise, and make it too easy to welcome anything that might come in its place as relatively better. Archives installed on that center floating table antagonize surrounding artwork based on other places, creating dreamscapes and nightmares of gentrification and development. The pair of curators work together in an ongoing project called Port to Port, which investigates, as they carefully state, “how urban zones are globally networked through processes of economic investment and trade, facilitated and accelerated by telecommunications and finance. Symptomatic of the neoliberal urges of global capitalism, these processes lead to the creation of homogeneous forms of infrastructure and design.”

New City: The City in the Sea from liam young on Vimeo.

Gómez was struck by the amount of construction he’s seen in Dallas on trips to and from the airport via DART, with cranes in every frame as he looked out the train window. The inspiration for the exhibition came from the shape of Dallas. Violence against the Trinity has made that shape, and the thorough writings of Laray Polk that guide visitors through Wide Open articulate the wastefulness and disregard for the environment not exclusive to Dallas but key of its infrastructure and approach.