We’ve been having a fair number of conversations in the office lately about the tragic shooting of Jordan Edwards by Roy Oliver, a Balch Springs police officer, and about how race impacts use of force by police. Which is in part why I have been so intrigued by the recent study published by UTD professor Alex Piquero, among others, which found that there is no correlation between the respective races of Dallas police officers and suspects in the use of non-lethal force.

If, by and large, DPD officers are not racist, or at least race doesn’t correlate to their use of non-lethal force to any statistically significant degree, that feels like a big deal. But it’s hard to feel good about race and police relations in light of the use of lethal force against Jordan, an unarmed black 15-year-old. As we’ve sat around our desks trying to understand what happened, especially after Oliver’s 22-page account was released, a few questions have crystallized. Is Oliver a racist, who pulls his gun on Hispanic women drivers and young black teens? Is Oliver an officer with an anger and/or reaction problem, who is too quick to pull, even when off-duty? Is he neither? Or is he both?

When I talked to Alex Piquero about the study, he mentioned the Caruth Police Institute, a research organization housed at DPD headquarters. When I told him I’d never heard of it, he suggested that I talk with Sgt. Stephen Bishopp, the research director, and a co-author of the study. So I gave him a call. His take? That our biggest concern about our police force shouldn’t be race. It should be mental health.

Do a lot of other major metropolitan areas have this kind of in-house police research institute, or is Dallas unique? No, you’re talking to the only one. As far as I know from talking to organizations from other countries, we’re the only one anywhere. That’s why, when I went to a meeting last fall at the National Institute of Justice, they had a meeting to talk about developing officers into researchers so they can start to really get into evidence-based research, to actually have practitioners involved rather than just having outside academics come in and tell the police what they need to do or what the numbers say. Having the officers merge with the researchers. There’s a term that we use in our little circles called “pracademia”—practitioners who are academics and vice versa.

I had no idea the Caruth Policy Institute even existed. How did it start? About 12 years ago, through a large grant, the city of Dallas, UNT, and UTD came together and formed this institute. The goal was to teach leadership development for the Dallas Police Department—sergeant, lieutenant, and so forth—like the FBI Academy. But we also have a part of the institute that was designed around doing research, primarily for DPD as they needed it. But it’s not just about crime analysis or collecting numbers. It’s evidence-based policing: using empirical studies, statistics, research design, and methods to really pull out what works, what doesn’t work, and examine data as we go.

So, how did a cop get involved with statistical analysis? Up until I came along, they had UT Dallas professors fill this position, but it wasn’t a full-time thing for them. As soon as I graduated with a Ph.D. from UT Dallas in Criminology in 2013, they brought me over here to be the research director.

Who decides what kinds of research projects you take on? Me.

Do you have a mission statement, or how do you determine your priorities? I have a dual focus in my research. One is to really examine the use of force, and various of aspects of that, including what is called general strain theory. Very briefly, if you put any person under enough stress, they’re bound to do something that they wouldn’t normally do. I look at various strains in officers’ lives, not just their conduct or behavior at work, but also their mental health. How does an officer who’s burned out react? How does an officer who reports being more angry act? I examine correlates to the use of force, with the mindset that healthy officers—both physically and mentally healthy officers—are naturally going to be better officers. Just like any profession, somebody that’s mentally healthy and engaged and physically healthy will do better at whatever job they do.

The less-than-lethal use of force study that you recently completed, which was published in the American Journal of Public Health in July, found that race doesn’t play a role in the use of non-lethal force by Dallas police officers. I believe it was the first study of its kind to not only look at white-on-black use of force, but at a dozen different relationships, including white-on-Hispanic, Hispanic-on-black, black-on-white, etc. What were some of your takeaways? Well first, there’s a body of research that’s beginning to build that drills down to the individual interactions between the officer and the citizen, rather than looking at these macro level numbers that other broad studies have looked at. You have to drill down to the individual interaction. What does the officer know and what does he see? What are the suspect’s actions? What are the suspect’s behaviors? All of that plays more into what goes down than anything else. When you send the police into the areas with the most crime, that’s generally the areas that are lower on the socio-economic scale, and are predominantly black and Hispanic in urban areas. You are going to see at these macro levels, because agencies are largely white and male, that white males have a disproportionate use of force against minorities. But when you look at the individual factors, you’ll see that, in fact, race as a driver or as a main independent variable just disappears. What matters more now is, was the officer assaulted? Did the officer come up on a crime in progress? Was the suspect intoxicated? I think the implications of our study are more for the research community than the policing community. It’s telling researchers, “Look, if you really want to know what’s going on in policing, stop looking at these great big, broad macro numbers, because it’s not giving you the whole picture.”

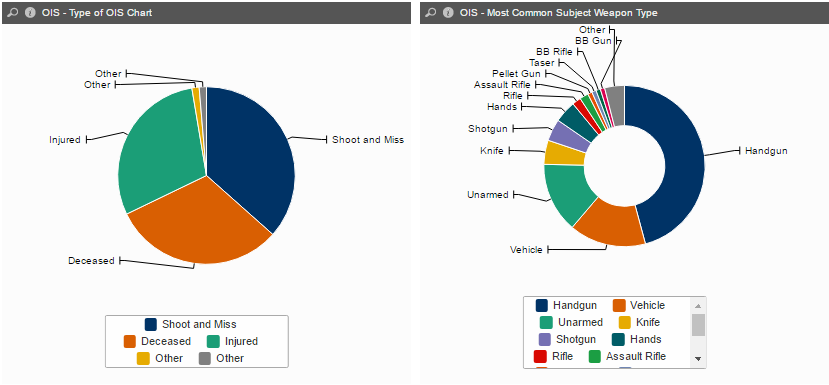

What’s the next research project that you’re planning to tackle? The Dallas Police Department has dumped 12 years worth of officer involved shooting data out there on the website that you can look at. We’re really drilling down to some of the individual factors there, such as suspect behavior and the location, because location matters to some extent if you’re working in a part of town where you’re constantly dealing with violence and being attacked. We’re looking at situational factors for the suspect and for the officer. What’s the officer’s education, because there’s some research out there that indicates that the more education an officer has, the less use of force they may use. Officer tenure, how long they’ve been here. Certainly the 27-year officer Bishopp would approach a scene much different than the one-year Bishopp did, I promise you that.

I have another survey that’s just getting off the ground. I’m working with some researchers in the UK to really look at mental health and well-being, how stress affects officers in both countries, because there’s no comparison that’s ever been done like this before. For instance, what’s the pension thing doing stress-wise to officers? Their physical well-being, their mental well-being, how they feel about jobs, burnout, anger, depression, all of that. How do Dallas officers compare to the UK folks who are also having pension problems and low pay and having trouble hiring officers?

The use of force and wellness are often very connected. I can’t stress this enough—that we need to concentrate in this country on mental health. Outside of the United States there’s a much greater, more urgent push to have mentally stable officers, and to make sure that officers who are here for a while, for a long time, that they manage stress, they understand their stress, and they take steps to control that.

Even your job, if you go to work all stressed out and do an interview, or you write an article, and you’re just mad and angry and burned out, that article’s going to look much different than you would write if you were feeling good about your job and loving your work, you know what I’m saying?

Right. I’ve been known to go on a tirade on occasion. In your job though, and I’m not downplaying it—please don’t take it that way—but if you write something that’s kind of crappy, somebody on Facebook will tear you up. Of course they’ll do that anyway, because you know everybody on Facebook’s a professional and knows more about your work than you do. But if an officer goes out and makes a split-second decision that’s driven by some problems he’s having, well, guess what? He ends up indicted or fired. Or gets killed or kills somebody else. I hope there’s some urgency that starts to build in this country to really give some meaningful help or education—or just look at the data to inform policies—for police officers.

The Assist the Officer Foundation provides confidential counseling to police officers that is entirely independent of the Dallas Police Department. For more information, visit their website.