The lead-up to my recent re-arrest by the U.S. Marshals Service and subsequent illegal four-day detention — a detention that only ended after one of the nation’s most prestigious law firms threatened to go to a judge — began a week prior. On Thursday April 20, I walked in to the Volunteers of America halfway house in Hutchins, Texas, for my biweekly case manager meeting with Victoria Dean, a VOA staffer. In the course of our conversation, I noted that I was doing an interview with VICE the next day, and that PBS would be coming a week later. Dean asked me if I had checked with the Bureau of Prisons on that; I replied that I had not, as I was not required to do so. As I explained to her then, the Bureau of Prisons Program Statement on News Media Contacts is the relevant policy document; it does not give the BOP the right to interfere with an inmate’s access to the press. Dean said the BOP requires halfway house staffers to notify them when a resident is about to speak to the press. I told her that was fine and left.

Later that afternoon, Dean called me at home and said she had spoken to BOP representative Luz Lujan, who had said I was required to fill out some forms before any interview, and that media representatives would have to do likewise. I told her I would do so as soon as the program statement granting the BOP the right of prior review was provided to me.

The next morning, the crew from VICE met me at D Magazine, and we began shooting for an episode of Cyberwar, to be aired next September. On camera, I called both Dean and Lujan, leaving messages to the effect that I still hadn’t heard from them on this imaginary program statement and wondering aloud if Lujan might not perhaps be thinking of an entirely different form, one which a news media representative is required to submit to a prison in order to gain access to an inmate, on the prison grounds. Those clips have now been made public by VICE.

I didn’t hear back from either Dean or Lujan on this over the following days. The next Wednesday, when I was summoned to the VOA for a random drug test, I saw the director, Merrill Wells. He asked me if I’d gotten the forms taken care of, and I told him I needed to speak with him about that. He said that he had a meeting right then. I said that perhaps it would be best if the matter were discussed in some more formal manner anyway. He replied that he would in fact be available to speak right then. I briefly explained that the BOP’s request, facilitated by Dean, was illegal and contrary to both BOP policy as put forth in the program statement as well as all current readings of the Constitution as applied even to inmates, and reminded him that I’d been doing interviews without any approval whatsoever for four years, both from prison and from his halfway house, and that his staff had been well aware of these things. He said that he had not been aware of this, and that they were merely required to report any press interviews, and that this was laid out in their operating guidelines.

After urinating in a cup for the glory of the state, I walked back to Dean’s office to see these forms she had been given. Dean was in Wells’ office across the hall, and the two were speaking with some degree of agitation, though I couldn’t make out what they were saying other than my name, which I consider the most wondrous of sounds and to which I have trained my ears. When the two came out, they were surprised to see me. I reminded Dean that she’d told me to pick up these forms. We all went in her office, and I again explained why their position was criminal and immoral and whatnot. But I took the forms with me.

That afternoon, I received a call from Dean and Wells, which I recorded; it’s available here. As can be heard, Dean tells me that my failure to fill out one of the two forms and to require media representatives to fill out and submit the other before interviewing me would be regarded as a “refusal.” Here she refers to a “Refusing an Order” infraction. I reply, at inimitable length and unwieldiness of tongue, that if the state and its servants believe that a refusal to comply with unconstitutional and imaginary rules that the state itself refuses to identify constitutes a refusal, then, by golly, what a wonderful world we have created for ourselves. Then I inform them that I am recording this conversation and will be “uh, submitting it” (I hadn’t actually decided what one does with a recording of this sort), and that it is my right to do so (which it is; laws on recording vary from state to state, but in Texas, one doesn’t even have to inform the other party, which I do just for fun).

Afterward I went on a Houston/Dallas radio show hosted by Kenny Webster, who was filling in for some other fellow, and whose other program, Pursuit of Happiness, I appear on about once a week. I explained the situation up to this point, and we attempted to get Luz Lujan on the phone but only got as far as her voicemail message, which we promptly mocked.

Shortly after that, I received another call from Dean, who said Lujan wanted to do a conference call. That call is here, and was relatively short since Lujan hung up after I told her that I would not speak to her or any BOP official without recording on my end, and that at any rate we had nothing to discuss as I merely wanted her agency to cite the rule that I was being threatened into following. Also I wanted to play video games, which I subsequently did, after first having the two recordings sent to the Courage Foundation and Free Barrett Brown organizations to be uploaded.

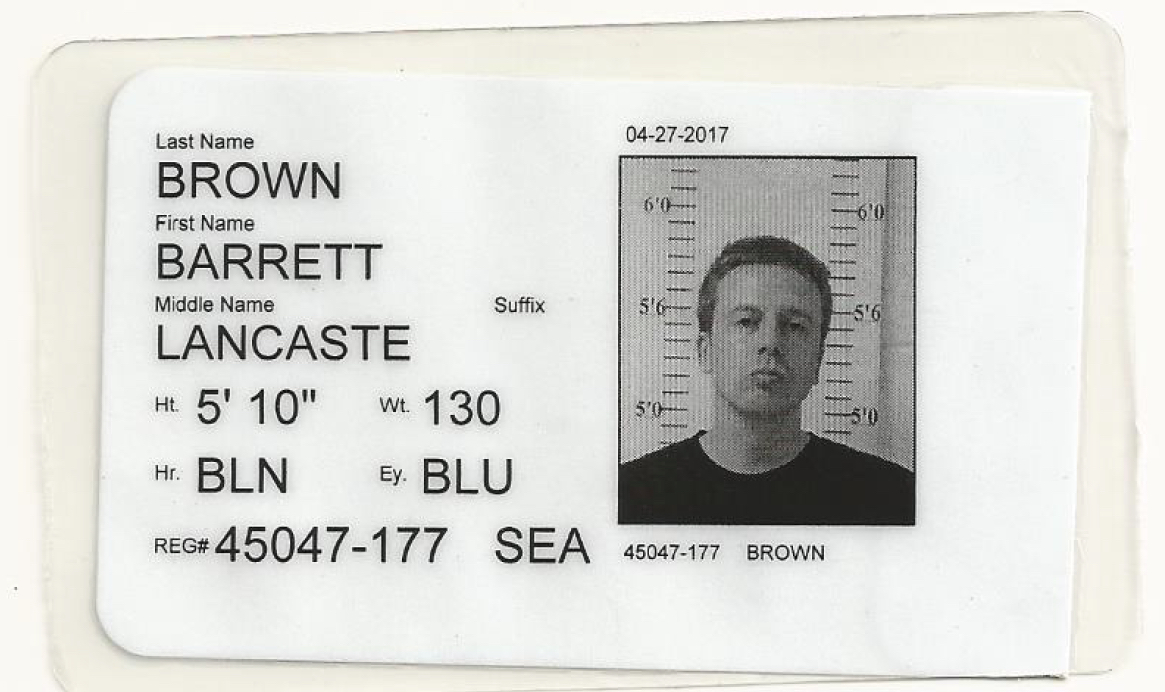

The next morning, I received a call from the halfway house telling me to report there immediately. I actually had to go in anyway for my twice-weekly regular check-in, but clearly this was something out of the ordinary. When I arrived, halfway staffer Woody Hossler asked me if I was recording, and I said no. Wells arrived and told me that he didn’t know what was going on but that the BOP had said that I should be called in and made to wait. I made a series of calls to journalists I know, as well as to Dallas City Councilman Philip Kingston, who started looking for a lawyer. At around 10 a.m., two U.S. Marshals arrived and took me into custody. I was taken to the Federal Building and shortly after was transferred to Seagoville Federal Correctional Institution, which has two jail units for those awaiting trial, sentencing, or further transfer, and where I spent the bulk of 2014 writing columns for D Magazine.

Incidentally, I caught up on a great deal of high-quality prison gossip over the next four days, including updates on people I wrote about in past columns (like the redneck Muslim gangster with whom I shared a cell in the SHU after our demonstration against a deranged guard, and who flooded our cell in the course of a mini-jihad against our captors). I shall resist the urge to digress, though it is strong. All of that will be covered in a separate piece a bit later.

At no point during my incarceration was I provided with any written explanation as to why I had been arrested. One staffer was able to tell me that the Marshals had been told by the BOP that I had “refused an order,” but no such infraction report materialized, whereas in nearly all circumstances such a report must be filed and provided to an inmate within 24 hours of the incident.

Meanwhile, David Siegal of Haynes and Boone, whom D Magazine publisher Wick Allison had retained for my use, had initiated communications with other BOP officials with a firmer understanding than Lujan of what they’d gotten themselves into, and made clear that the matter would be brought before a judge if I were not released immediately. Thus it was that on Monday morning, the counselor at Seagoville’s J2 jail unit summoned me to his office and told me, “You won. Get your stuff ready. You’re leaving.”

Woody Hossler, the aforementioned halfway house staffer, had to pick me up in his car and take me back to Hutchins, where I was given a breathalyzer and drug test before being cajoled into meeting with Wells, who this time had some other fellow in his office with him whom he identified vaguely as his new “program director.” After commenting that I “look mad,” Wells said that the BOP wanted me to sign two forms. I asked him what would happen if I didn’t. He replied that in that case we would “be back where we started” and that he would have to call the BOP. I asked who at the BOP had told him all this; he said that Lujan was absent that day and someone else was acting in her role. I spent about two minutes trying to get him to admit that I was being threatened with yet another unlawful arrest if I failed to sign these two inappropriate forms, an idea that he attempted to depict as wholly silly. I asked, for instance, if I could take the forms with me and talk to my lawyer first; he would only reply that he would have to call the BOP if I didn’t sign them right then and there. Finally I told him I would sign the forms if I were allowed to take copies with me; he agreed to this, all the while taking pains to note that he’s “not [my] enemy,” a regular refrain of his.

These latest forms may be seen here. One, the “Release of Information Consent,” I had already signed at my own insistence five months prior, when Lujan was telling reporters she couldn’t talk about my situation until I’d signed it. The other was one of the two forms I’d originally been asked to sign, “News Interview Authorization,” which is intended for inmates about whom a prison has been approached by the press. There was no more talk of my seeking permission to do interviews, and no more forms to be forced upon journalists seeking to speak to me. The “Media Representatives Agreement,” which the BOP had just last week claimed I was required to get press to fill out and submit for consideration, was no longer anywhere to be found.

As there has been some confusion in the press on this point, I will note again that federal inmates are not required to seek permission from the BOP to speak to the press, period. Some previous language to that effect was rescinded 17 years ago, as noted in the Program Statement (under “Directives Rescinded”). That’s why I was never given any infraction for doing so over the four years in which I did interviews from half a dozen different facilities, by mail and phone, and it’s why the BOP was not able to hold me in prison after Haynes and Boone threatened to go to a judge. The forms involved, as noted in the Program Statement, as well as the requirements described in another section that put forth conditions on press access to institutions — having to seek comment from the BOP, refrain from taking pictures without consent of inmates, etc. — apply entirely to a separate agreement that a news organization enters into in return for being allowed into a facility to interview a particular inmate, who himself has either given consent or denied it via the News Interview Authorization form, which is presented to him within 24 hours of a qualifying outlet submitting the Media Representative’s Agreement. I have filled out the authorization form several times, dealt with the BOP over four years, familiarized myself with the Program Statement and even filed grievances over the BOP’s failure to abide by it (such as when Alex Winter submitted a request that was ignored for eight months before being rejected).

I’m reiterating this because the BOP thrives on ambiguity and would like nothing more than to see major news outlets continue to ignore this story on the vague grounds that maybe I broke the rules and perhaps the BOP didn’t actually just conspire to deprive countless media outlets of their very specific and unambiguous right to speak to an American citizen, and then retaliate against me with an illegal arrest when I failed to help them do so. The BOP, like all U.S. “law enforcement” and intelligence agencies, depends for its continued de facto extra-legal powers on a press corps that is largely incapable of sorting through facts, that is easily distracted, and that cannot even be depended upon to defend its own rights, nor the rights of individual journalists. Already I have documented in my columns for D Magazine and The Intercept, via documents obtained by various means, the demonstrable criminality of this organization.

There may very well be further legal action against some of the culprits in this case, just as the FBI and DOJ officials who illegally tracked down donors to my legal defense fund are now struggling against a lawsuit filed a few months back in California. But what interests me most is whether the establishment press that saw fit to count me among their number last year when they gave me the National Magazine Award for commentary, among other honors, will also see fit to report that I am once again being subjected to state-sanctioned retaliation for trying to defend our common right to report the news. This is not just about me; it is about this republic and the dark places to which we are headed.