For the first time in the city’s history, not a single council member will be term-limited out in an election. On May 6, 11 of the seats will be contested. But will anyone vote? Even in a state that’s never prided itself on electoral turnout, Dallas’ aversion toward the voting booth is exceptional.

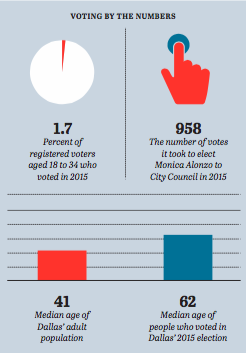

In the city’s last municipal election in 2015, only 6.1 percent of eligible voters showed up at the polls. A Portland State University study of the most recent mayoral contests in the country’s 30 largest cities found that turnout was low almost everywhere, and that Dallas had the lowest rate of voter participation in the U.S. Fort Worth, tagging along to the bottom of a deep gorge of electoral apathy, was second worst, with 6.5 percent. (Turnout, as it does elsewhere, increases for presidential elections; about 60 percent of registered Dallas voters cast ballots in 2016.)

Talk to elections officials, political organizers, and experts in North Texas, and they’ll quickly run out of fingers to point at culprits for low turnout. To name a few: off-year city elections, general disillusionment with politics, candidates with little name recognition, a large Latino population that votes less than other demographic groups, gerrymandering and entrenched incumbents feeding the perception that change is impossible, a historically top-down local power structure that favors private and corporate interests.

In the past, turnout in non-presidential elections here and in the state has been highest when voters were deciding on controversial proposals, rather than candidates, Dallas County Elections Administrator Toni Pippins-Poole says. Votes on bingo and horse racing regulations in the 1970s and ‘80s come to mind.

Of course, every election is about issues, although that’s not always so clear. The personalities of local campaigns pale in comparison to the national names of presidential races, which draw an inescapable level of media attention. This persists even if voters are affected more by the outcomes of municipal elections, and vice versa.

Among many other things, the ostensible nonpartisanship of Dallas County elections may play a role in depressed turnout, Pippins-Poole says. But she lays most of the blame with a lack of voter education, which could be improved by local jurisdictions, and candidates themselves. This could include something as simple as voter guides, which are not especially common in Dallas County, Pippins-Poole says. It also takes traditional methods, candidate forums, and media coverage, as well as the use of new technology, whether it’s social media outreach or more helpful city websites. Voter education shouldn’t just cover when and how to vote, but why: the issues that matter, and the fact that in local elections, they really do matter.

The Dallas County Civic Alliance, an organization created ahead of last year’s presidential elections (what better time to capitalize on voter interest?), is dedicated to doing just that, hosting forums with city council candidates and reaching out to voters, particularly young people and first-timers.

The organization, which bills itself as nonpartisan, tries to strip away the personalities and politics, focusing on issues that will resonate with Dallas residents, says Benjamin Vann, the founder of DCCA.

“In order to get people to turn out, there has to be a why,” Vann says. It could be criminal justice reform, or the threat of predatory lending, or school district tax ratification. Whatever takes an abstract civic idea—voting—and makes it feel practical and necessary.

Vann says the organization also helps connect volunteers with other groups, including the NAACP, Faith in Texas, and the League of United Latin American Citizens, that can help build a habit of political involvement after an election cycle finishes. For much of Dallas’ history, the city has lacked a strong activist base that can energize people who remain untrustworthy of elected officials, that can convince first-time voters it’s worth going to the polls, Vann says. He does, however, see this changing among Dallas’ younger residents.

Increasing turnout requires building a new “culture of voting,” particularly among young people and Latinos, says Ramiro Luna, a community organizer involved in voter outreach. Political campaigns, by their very nature, are designed to reach out almost exclusively to repeat voters, and fail to engage the electorate by ending after an election. Creating that culture requires more constant engagement and making an appeal to first-time voters, outside of a campaign structure.

Luna, who helped elect state Rep. Victoria Neave in 2016, is hopeful that the attendance at large rallies in Dallas protesting the president in the first few months of this year can be translated into participation in local politics. At January’s Dallas Women’s March, spearheaded by Neave, volunteers organized phone banks and registered voters.

“Our strongest weapon is our vote,” Luna says. “Right now there’s a lot of energy floating around, but unless we harness that energy with voting, it’s not going to be as crucial as it can be.”

Low turnout in municipal elections does not necessarily mean that Dallas is devoid of a sense of civic responsibility. Not voting is itself a democratic decision, says Allan Saxe, a political science professor at UT Arlington. Keeping your lawn tidy, or caring for a rental property, is an act of civic responsibility.

An especially mobile population may partly account for the lack of voter engagement in North Texas, as compared to other parts of the country, Saxe says. Political personalities here tend to be less inflammatory than, say, Rahm Emanuel in Chicago, which saw a 33 percent turnout for its last mayoral election. And Saxe is skeptical of vote-by-mail allowances in states like Oregon (Portland: a whopping 59 percent) because of the potential for fraud.

Mostly, Saxe says, it’s that many potential voters are content and unconcerned with city governance as long as their trash gets picked up, their tap water is turned on, and their 911 calls get responses.

Except we do have axle-breaking potholes and unanswered 911 calls, which recently contributed to the death of a 6-month-old boy. Not to mention the threat of bankruptcy from an insolvent Police and Fire Pension fund, and a Trinity River park that may not ever come to be.

In Dallas’ case, that old cliche about the electoral process turns out to be truer than in most cities. Because when fewer votes are cast, every vote counts more.

Want to learn more about this topic? Come to our office on Wednesday for the latest Happy Hour With an Agenda, where we’re talking city politics with writers from every major publication in the city.