The Partnership for Southern Equity has released a new study that looks at the history of racism and segregation in the city of Atlanta and how it participated in shaping the city’s transportation network. It’s an angle on the history of 20th century urban growth and suburban sprawl that is rarely looked at this directly or with so much detail. What the study reveals is that the social history of 20th century America was as much of a contributor as economic factors in the shaping of the built environment of Atlanta, as well as many cities in the southern part of the United States, including Dallas.

Atlanta’s problems are Dallas’ problems: traffic congestion; long, arduous commutes; a inadequate public transit system; job centers in the north and poorer, largely African-American neighborhoods concentrated in the south. It is an urban landscape that reinforces social and economic inequality.

As Leah Binkovitz reports on the blog run by Rice University’s Kinder Institute for Urban Research, these problems are symptoms not merely of the economic gambit of post-war urban sprawl, but also of housing policies and social attitudes that reconfigured legal segregation into a pattern of urban growth that wrote a new kind of segregation into the new, post-war landscape:

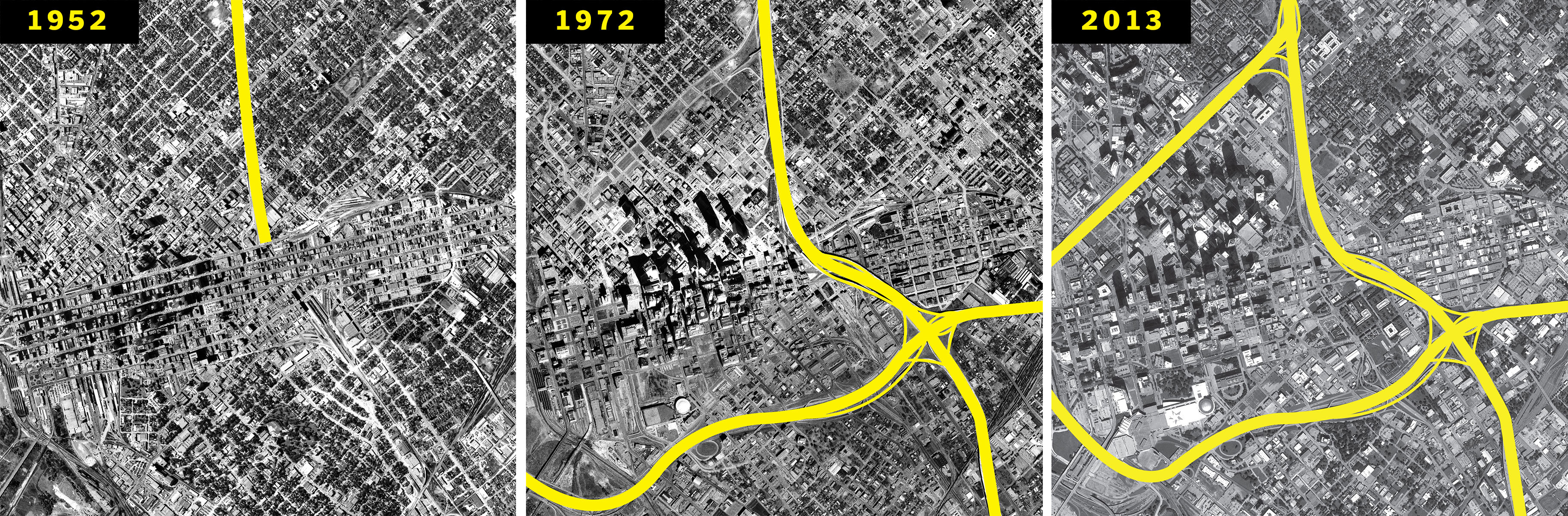

Like other cities, Atlanta was transformed by transportation and housing policies in the mid-1900s that subsidized suburban growth for white homeowners, leaving the city core underfunded and crippling the ability of black families to build wealth.

“The effects have lasted for generations,” the report reads, describing what some have called the “$120 billion head start.” Those policies fueling residential segregation were inextricably tied to transportation in the region, said Alex Karner, a city planning professor with the Georgia Institute of Technology and co-author of the report.

As white families took advantage of racist housing policies and lending practices and headed to the suburbs, “the economic activity was still concentrated in the cities, so they needed some sort of link,” he said. Shortly after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that segregated schools were illegal, “the freeway system comes online,” often running right through communities of color.

Atlanta was one of the earliest southern cities to invest in public transit, beginning to build the MARTA system in the 1970s. However, rather than viewing public transit as a way of overcoming some of these social inequalities, the shape and design of the network was largely conceived as a way to connect the suburbs with the downtown business core. Does this sound familiar:

Though the metro area was largely segregated between suburbs and the central city, business elites still maintained an interest in making downtown economically vibrant and facilitating connections to the suburbs to manage traffic. Their interest in rail helped create MARTA, thanks to an act of the state legislature in 1965. Early on, the agency faced opposition from black voters, who rejected a proposed property tax in 1968 because they were “dissatisfied with a lack of input and the proposed design’s emphasis on suburb-to-downtown access,” the report explains.

In response, MARTA appointed a key critic to its board and reworked plans to include a major bus expansion and a rail line serving largely black neighborhoods as well as other changes. Black voters, in turn, helped pass the next funding referendum in 1971. But the measure failed in two of the four counties where MARTA was established. The two counties, notes the report, were rural and largely white. “Racial fears were certainly part of their opposition.”

Other scholars have chronicled “this radicalized animosity toward transit” in Atlanta, including Jason Henderson, a geography professor at San Francisco State University. “Since it was established in the 1960s,” he wrote in a 2006 paper on the politics of automcobility in Atlanta, MARTA “was jokingly referred to as ‘Moving Africans Rapidly Through Atlanta.’”

Now, the study continues, Atlanta faces a new problem that also echoes the pattern of Dallas growth. Poverty that was once contained in the central city is spreading to the suburbs, which presents is own challenges for planning future transportation. The key to reversing this trend, Binkovitz argues, is not merely transportation, but also affordable housing:

So while it points to the need for dedicated funding and integrated regional transit, it also touches on affordable housing as a way to address traffic problems. “If we had a better fit between affordable houses for low-wage workers and the location of jobs, that’s also a transportation mitigation but its strictly housing,” said Karner.

In other words, the key to solving ongoing issues of poverty, inequality, traffic congestion, and growth are tackling precisely the two urban issues – public transit and affordable housing – that have dogged Dallas more than any other.