“Our Parks Department can’t find anything named after Ned Fritz. There is a Fretz Park in Dallas, but that was named after a former Park Board member,” wrote city spokesperson Richard Hill in response to an email inquiry. As far as streets, he said, there’s one. “We have no record as to why it was named Fritz and no records of any other streets named Fritz or Ned Fritz.”

The reason there are no parks or streets in the city of Dallas named for Fritz is a question that mostly answers itself. He was a lawyer, communicator, organizer, and conservationist. He saved land from highway development and forests from a barge canal. According to community health advocate and environmentalist Jim Schermbeck: “Without Ned Fritz, we might be looking at one long industrial ship channel from South Dallas to Houston. Without him, we might not have a Big Thicket forest, or at least not one as large.” One of his most enduring legacies, Schermbeck says, “is the idea that citizens themselves should be the decision makers in what resources are sacrificed and for what purposes, and which ones are preserved for the future. That’s still a very radical notion when put into practice.” An especially radical idea in Texas, he says, in the 1960s and ’70s, “when Fritz was advocating for open spaces for their own sake.”

The Great Trinity Forest is one of those open spaces Fritz fought for and managed to save. Saving the forest in this instance means that people in 17 counties — including Tarrant, Dallas, and others downriver — went to the ballot box on March 13, 1973, and voted against bonds for canalizing the Trinity. That stopped the prospect of clearcutting along the river, which in turn saved the forest. And because the majority of voters were not interested in financing the barge canal, it meant the federal government wouldn’t subsidize the project to the tune of $1.6 billion.

The pursuit of federal subsidy for making the Trinity navigable goes back to the 1850s. The first sizable amount sunk into the project came during Theodore Roosevelt’s presidency and went toward building locks and dams. In 1909, the year Roosevelt left office, the first lock and dam was completed in Dallas County, near McCommas Bluff. By 1917, a total of eight locks and dams had been constructed, but the additional 27 proposed were never built. The project languished until the presidency of Lyndon B. Johnson.

President Johnson and Congress approved the Rivers and Harbors Act of 1965, which authorized a basin-wide plan for the Trinity River. Legislators, however, wanted a vote at the local level before appropriations were considered for the navigation component (the act also contained flood control measures). It was one of few instances where the public had a say in whether to build the canal, and “no” won the day.

It was a small-margin victory that entailed an awareness campaign in advance of the March 1973 vote, organized by a coalition called the Citizens’ Organization for a Sound Trinity (COST). Those behind the pre-election effort were a diverse group of people with both liberal and conservative leanings. Some people opposed the project on economic grounds. The canal was a boondoggle. Fritz opposed the project because he thought it would jeopardize flood-control policy and result in clearcutting along the river. And he believed, in concert with others, the project would wreak havoc on the ecology of the entire river.

The COST mobilization put the kibosh on the dream to make the river more than it is; or, so it seemed. Another scheme for remaking the river emerged in the late 1990s, called the Trinity River Project. If the Dallas floodway wasn’t going to be transformed into an inland port and turning basin on the federal dime, the thinking — if not the sentiment — went, then it would become a world-class park with the Great Trinity Forest as its crowning jewel.

The narrative for a park has been pitched to voters since 1998. In that year, the local electorate was asked to vote on a $250 million bond package that included a Trinity Parkway. The vote swung in favor of those promoting it, but over the years, what had been sold to voters on the ballot as a “parkway,” with access to a park, has been revealed for what it really is: a multi-lane, high-speed toll road set between levees in the floodway.

Politicians, boosters, and the city’s only newspaper, the Dallas Morning News, have told voters to accept the toll road or risk losing the park and even flood-control measures. (The editorial board at the News, it should be noted, has softened its stance.) Neither the city nor mainstream media has explained after all these years how federal dollars and local funding are intertwined, nor what projects are actually holdovers from the 1965 River and Harbors Act. As a result, plans for a $1.9 billion toll road in a floodway remain the most contentious infrastructure project to date.

If it feels like a familiar fight, says Schermbeck, that’s because it is. “The Trinity toll road fight is just another iteration of the barge canal fight, which was itself another iteration over the fight to industrialize the river,” he says. The Trinity River is a watershed and the area’s most important water resource. “It’s not a corridor for cars, or a canal for barges,” Schermbeck says. “It’s our water mover. In this respect, the residents fighting the toll road are Ned Fritz’s direct political descendants.”

Fritz, in his final years, attended meetings, signed petitions, and spoke out against the toll road. David Gray, a board member and past chairman of the Texas Conservation Alliance (TCA), worked closely with him on the toll road issue. He says Fritz thought that the Trinity River projects were smaller scale versions of the barge canal “in that they were attempts to exploit what should be a natural resource and floodplain and green space and park at the expense of duped taxpayers who would subsidize the project for the benefit of the rich and well-connected.”

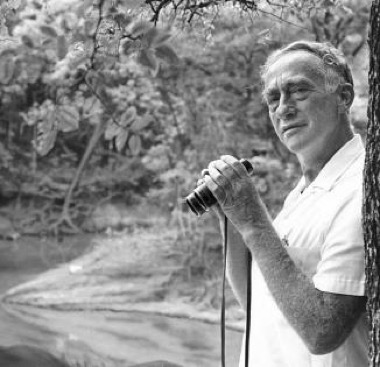

According to several sources interviewed, Fritz had a rare combination of traits. He could read technical documents — Environmental Impact Statements (EIS), legislation, proposed rules, legislative history, scientific studies — and translate them into understandable language. “Ned read and studied documents and legal briefs extensively,” Gray says, “and he also wrote faxes, memos, letters, and advisories and formulated positions on issues that were easy for people to understand.” Janice Bezanson, current director of TCA, says Fritz “didn’t worry whether someone was Democrat or Republican, old or young, rural or urban, what ethnicity they were. He worked with everyone.”

Genie Fritz, Ned’s wife, a committed conservationist in her own right, says his opposition to the toll road was primarily “about building in a floodplain and the destruction it might cause to the forest downstream.” The massive toll road, if built, would block access to the green spaces, she says, which defeats the purpose of the Trinity River Project. She says all that is really needed is a slow-moving parkway with a modest number of lanes, like the one proposed in 2007 by former council member Angela Hunt, a proposal both she and Ned supported. “A road like that could deliver people to natural areas, carries a small footprint, and could rebound inexpensively when it floods,” she says.

A large part of the problem with these projects, Genie says, is that “people look to Fort Worth as something that can be done with the Trinity River in Dallas, but it’s not possible.” That’s because Fort Worth only has to contend with the West Fork, she says. Dallas, on the other hand, is the convergence point of the West and Elm forks, along with other tributaries, all headed into the main stem of the river. “The Trinity River in Dallas has much more volume because of that,” she says, “and it also has to facilitate the city’s treated wastewater that’s poured back in.”

Her views on the river reflect a lifetime of service to conservation issues, and she’s aware activism sometimes comes at a price, such as the lack of acknowledgement when the official history is written. She’s not surprised there are no streets, parks or trails named Fritz, or that none of the city literature on Dallas’ natural amenities mentions Ned’s role in saving the Great Trinity Forest. She would like to see that change.

[Editor’s note: for an explanation of the Trinity Project, go here.]