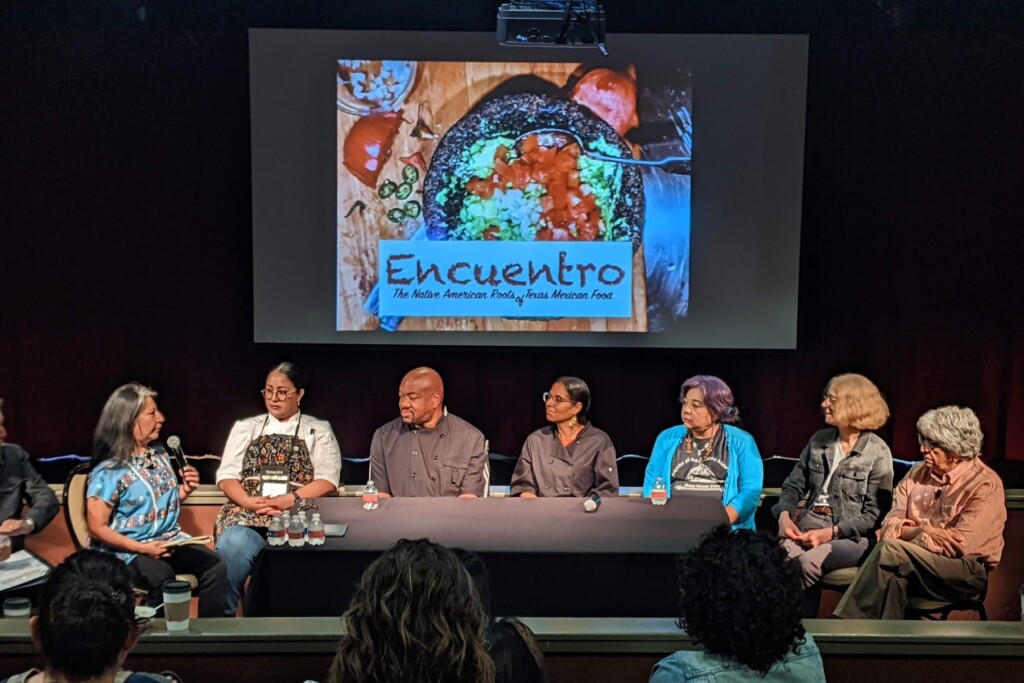

Last weekend I had the privilege of attending Encuentro, a conference in Houston on the importance of indigenous native practice in Texas food. Scholars and chefs talked about historical findings and family traditions. They compared notes on ingredients and techniques. They interviewed each other, too, with the scholars asking cooks questions and vice versa.

And, of course, there was cooking to try.

I found the whole thing fascinating, taking copious notes throughout. Hopefully, my writing will be better-informed and full of more helpful context in the months to come. For now, and with gratitude to Encuentro and its main organizers, Christine Ortega and Adán Medrano, here’s a quick highlight summary of direct lessons learned at Encuentro.

We all could be eating many more local ingredients

When we talk about local produce, too often we talk about flora and fauna that happen to be grown here, whatever their original connection to the land. Even the Southwestern food movement that swept across Dallas for 20 years had a limited imagination about local produce: it embraced peppers, corn, and certain herbs (like hoja santa and cilantro) while leaving many more ingredients behind.

Discussing and tasting those half-forgotten ingredients at Encuentro, I felt like a world of possibility remains for Texas chefs to explore. Andrés Garza, from acclaimed Austin taqueria Nixta, served tamales made with a mixture of blue corn and mesquite flour. Mesquite pods and beans, dried and converted into flour, have just as long a history as corn in native cooking. Dallas’ own Luis Olvera told the panel that he had found a text from the 1770s stating that tortillas were a mesquite product. Garza likes to make fermented mesquite tea. If you can find mesquite flour, Medrano’s book Don’t Count the Tortillas has a quick, easy dessert recipe for mesquite candy balls.

If mesquite has untapped potential as a staple ingredient, the prickly pear cactus’ fate is more insulting. It is best known in Dallas today as a flavoring in margaritas, but paleoethnobotanist Dr. Leslie Bush told us in a talk about local evidence for prehistoric cooking that prickly pear season was “the happiest time of year.” Bush also outlined traditional uses of amaranth and chenopod, a tiny relative of quinoa. Amaranth isn’t just a leafy green; the high-protein seeds can make atole or a bread flour.

I’ll list just one more example so this article doesn’t go on forever: Dr. Lilliana Patricia Saldaña, of the University of Texas at San Antonio, recommends cooking tomatillo husks rather than throwing them away, and specifically suggests mixing them into nopalitos.

Authenticity can be a prison, and creativity can mean freedom

Almost everyone has memories of family elders cooking foods the “traditional” way, in whichever tradition you come from. But those family traditions do not always represent ideals. Maybe ingredients were substituted due to poverty, or processed seasoning powders and pudding mixes played big roles. Many of our ancestors were forced to cook “authentic” dishes to survive, or because they were enslaved. Would Grandma always want you to cook things her way? It’s complicated.

Nadia Casaperalta, a culinary instructor at South Texas College in McAllen, put this very eloquently, in my favorite quote of the whole weekend.

“We need to play more,” she said. “Our ancestors didn’t get to play. My grandmother probably learned this consommé cooking for another family. They didn’t get to play, so I want to honor them by playing and getting inspired by curiosity for the ingredients that the land provides.”

Later, she added another remark about people who demand that foods remain unchanging and “authentic,” as if frozen in time: “You’re limiting the advance of our art, and you’re limiting who we can be.”

Many Italian-style aperitivos are a little bit Mexican

If you’ve ever enjoyed a bright red aperitivo—like Campari or its American rivals—you’ve experienced a little bit of Mexican culture without realizing it. The red coloring is traditionally derived from cochineal beetles, a species native to Mexico, the American Southwest, and dry areas as far south as Peru. The beetle is dried, powdered, and used to add a bright red hue to drinks.

A cocktail at the conference was served with Campari to reclaim that brand as Mexican. It isn’t anymore—Campari switched to artificial food coloring in 2006—but many American producers of similar aperitivos still use native American beetles for their dyes. Drink bugs; buy American!

Native Texan food has a naming problem

What exactly do we call the foods that represent Texas’ historical heritage? “Texan” is flawed because people associate the word with chicken-fried steak and brisket. “Mexican” obviously isn’t right, while “Tex-Mex” is commonly understood to refer to a specific subset of more recent culinary inventions, especially from the late 1800s. “Texas Mexican” helps clarify that our native cuisine is a regional variation of Mexican food, but the average reader might not understand how the phrase differs from Tex-Mex, or that the phrase denotes indigenous origins, since Texas and Mexico are present-day political entities.

(Digression: Tex-Mex, as applied to food, came to fame as an insult used by Diana Kennedy in 1972 to declare Texas Mexican food inauthentically Mexican. Then Texans adopted the term with pride, and now many menus serve a mix of classics like carne guisada and more recent inventions like fajitas under the Tex-Mex banner. “When I was a child, we didn’t call it Tex-Mex, we called it Mexican,” said Steven Pizzini, whose family has a 90-year history making Mexican food in San Antonio, in a completely unrelated panel hosted by Texas Public Radio a few weeks ago. That panel is viewable on YouTube.)

In my head, I’m using the phrase “native Texan.” But cooks and scholars alike are still divided on the question of how to describe this food to outsiders.

An easy way to identify pre-Hispanic cooking methods

The Spanish first brought pottery to this region, so look on menus for dishes that aren’t cooked in pots. Pre-Hispanic techniques and tools include drying fruits, popping corn, steaming (like tamales), the molcajete, earthen ovens, fermentation, and roasting or searing with hot stones.

Of course, the later culinary fusions are wonderful, too. “Grape dumplings are a mashup of pre-colonization food and colonization food,” said Diana Parton Smith, a citizen and leader of the Caddo Nation. “And I am that mashup too.”

Update, 5/26: Dr. Bush kindly emailed me a correction to the above. Pottery (ceramics) existed in the Texas region before the Spanish arrived, but its usage varied among peoples; Caddo ancestors made “abundant” ceramics, she says, while people in central and south Texas made little and started late, just a century or two before the Spanish. Dr. Bush says her intention was not to erase the pre-conquistador history of pottery—that was my mistake leaving out a word in my notes—but to contrast it with more common and more ancient cooking techniques.

All food is political

One of the most frequent hostile comments food writers hear is “stick to food.” Readers are often upset when we point out the political roots of culinary problems, but politics informs food in countless ways, and we heard more examples at Encuentro.

Mexico’s middle and upper classes, one presenter told us, favored European-style bread over tortillas for many years, seeing tortillas as a symbol of lower-class native people. Two chefs talked about the nostalgic role of Spam in their families, because when the American government forced Native Americans to move hundreds of miles from their homelands, the government then had to supply the residents with food. Rebel Mariposa, of San Antonio, told us of her father’s abiding love for Spam tamales. Another political story played out in the introduction of Spam to Hawaii and Asia, and “government cheese” also played a role in the history of Tex-Mex queso.

Most striking was the story of amaranth. Because it had religious significance to native people, the Spanish tried banning amaranth. Natives saved the plant for future generations by burying seeds. Next time you eat amaranth, you’re defying a centuries-old autocracy.

Asking for the recipe isn’t always a compliment

Someone in the audience asked Parton Smith if she could share her recipe. She refused, because the important thing about food isn’t the food itself, it’s the connection between creator (giver) and eater (recipient).

“Sharing recipes is not the Caddo way,” Parton Smith told us. “Cooking the food is my gift to you. It’s a bond between us. That bond is lost when one passes a recipe as a commodity.”

“Food brings conflict”

We like to talk about how food brings people together, how you’re always welcome around a dinner table, and how the world would be a better place if everybody ate together. But in different ways, the presenters at Encuentro pushed back against that romantic narrative.

I’ll name one small example and one serious one. Small one first: food can create arguments and debates just as much as it can create unity. Think about your arguments with friends about which Halloween candy is the best. Imagine a family debate about the exact recipe for potato salad. Remember the phrase “too many cooks in the kitchen.”

Here’s a more serious example. The Spanish invaders saw the different ways that native Americans ate and used those eating habits as justification for oppression. Native tribes at the time of Spanish arrival did not eat in scheduled mealtimes. Instead, food was always being prepared at a central location, and community members could walk in and out as needed. The natives’ culinary repertoire also didn’t include separate types of foods specifically for breakfast. To the Spanish, these differences weren’t interesting—they were signs of an uncivilized people who needed correcting. In their hands, food became a propaganda weapon.

Don’t you dare cut a tortilla

Victoria Elizondo, who prepared some of the most spectacularly flavorful chilaquiles I have ever tasted, talked to the group about making migas at home. Her advice: never, ever cut the tortillas with a knife. Tear them with your hands. As she puts it: “If you use a knife, you’re disqualified!”

Get the SideDish Newsletter

Author