A few years ago, Amy Severson, co-owner of Sevy’s, reformed blogger, and all-around smart person, and I had what we thought was a great idea. We decided to write a book on the history of Dallas food. We began collecting bits and pieces of information and interviewed grandchildren of long-lost Dallas restaurants and food businesses. What we have found is unique and amazing and over the years we have published several almost-lost stories. Like La Tunisia, Eltee Dave’s Barbecue, The Woosie, The Golden Pheasant, Prohibition in Dallas, and, my personal favorite, The Amazing Mrs. Ida Chitwood. Since the Dallas Farmers Market is going through a new phase, we thought it would be interesting to look back and see how it all started. It’s going to take us a few posts to get the whole story out.

In the late 1800’s, Dallas grew, in large part, by supporting agriculture. It became a business “incubator” for the cotton industry, the most prominent crop of the region. Cotton was moved in and out of Dallas by the burgeoning railroad system. Most of the cotton was processed by large gin mills operated by Dallas merchants. Eventually, the rail system grew and created more stops at smaller outlying areas closer to farmers. This led to smaller mills popping up along the tracks train stops which gradually siphoned off the business trade from Dallas.

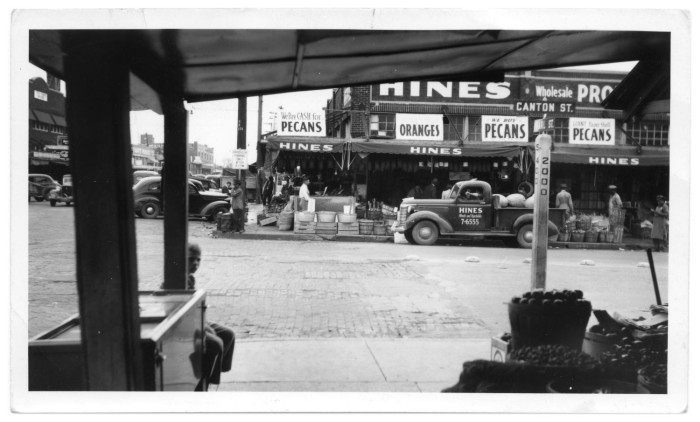

In 1897, the gradual decline in cotton shipments combined with a poor cotton crop presented a serious problem for Dallas economy. The Commercial Club, an organization of prominent Dallas businessmen, began to look for ways to support and increase importing and shipping other local farm products to keep the railroad cars full. The dealers along Pearl Street, once shippers of cotton, had to change. They became purveyors of chickens, turkeys, eggs, nuts, fruit, and vegetables grown all around North Texas. By 1906, business was booming. The total gross receipts of poultry and produce dealers in the new marketplace totaled just under one million dollars.

Horse drawn wagons from small rural crop farms–areas we now call Carrollton, Mesquite, Garland–would line up, pre-dawn, in the city’s downtown. Some came from as far as 150 miles away, their drivers regularly spending the early hours sleeping under their wagons in order to get the best spots along Pearl Street. There were so many that came to wait that downtown residents considered them a nuisance and compained. The city changed the law and farmers were were banned from downtown until the buyers opened their warehouses at 5 am. They had to sell their goods and get off the streets by 9AM.

They had only four hours to bicker and deal with the various middlemen whose responsibility was to find the best crops their buyers needed in markets. Rejected produce, either too ripe or bruised, was sold directly to housewives or house cooks who circled the wagons. Farmers returned to their homes and spent the remainder of the day picking crops and getting ready to repeat their migration downtown until their crops were depleted.

The mass production of the farm truck in the early 20th century opened access to Dallas’ market. As many as 250 trucks per day were coming to Pearl Street. Middlemen became incensed as buyers for local grocery stores and housewives would show up at the truck lineups at midnight. By making their purchases directly from the drivers, they got the best price and the best quality. The merchants had less to ship. Dallas was large enough to sustain the production of its local farmers distributed in a downtown market place

By the mid 1920s, serious concerns were raised about the sanitary conditions in the mix of privately owned businesses that comprised the Pearl Street market area. Some of the stalls were filthy. Many allowed non-farmers to sell imported produce, competing with local growers sales. At the end of the 1920s, the city passed an ordinance which restricted sellers to farmers rather than what they referred to as “hucksters” who sold product imported from as far away as Houston.

The residents demanded that the city create a Dallas-owned and operated famers market on the empty land nearby.

Stay tuned for part two.