Thank goodness for Jim Schutze, the Dallas Observer’s old liberal crank, who writes education posts so I don’t have to. He recently covered why you should vote for incumbent Dustin Marshall in the Dallas ISD District 2 race, where early voting ends today and day-of voting happens Saturday. He’s right. Marshall has proven himself an excellent trustee, and the attacks against him are lies designed to play into people’s worst political instincts. I’m going to go over some of that information again and add a few things, because it’s important you feel good about casting your vote for Marshall, in case you’ve been disturbed by some of the campaign rhetoric. (Here, by the way, are the boundaries of District 2, which encompasses much of the city’s center, from Lakewood to Preston Hollow.)

But I’m also going to address a few larger questions raised by Schutze’s piece and this follow-up take. Even if I’m covering the same ground a bit, it’s vital you hear this, because as Schutze writes, “The significant school reform achievements of the last several years hang by one vote on the school board. A vote for Lori Kirkpatrick, the anti-reform candidate in District 2, is a vote to roll back and destroy the entire reform agenda.” But I also want to look at something else at play here. Schutze wonders in each post why so many smart progressives are so wrong on education issues. It’s an important question.

At the risk of bringing a fact-checker to a culture war, we have to start with data. One reason many edu-educated progressives align themselves with moderates and Republicans on education matters is because the numbers lead us there. For example, this is why in four years covering K-12 education in Dallas, and in 18 months working for a teacher advocacy nonprofit, I have never had a conversation with a single education expert or reformer about vouchers, other than about how they don’t work. This includes Dustin Marshall, who does not and has never endorsed vouchers. Every serious education reform advocate in North Texas realizes that the rigorous data on vouchers shows null-to-negative effects in many recent studies. Vouchers are fine in theory. Like everything when it comes to education results, the elegance of the theory doesn’t work if the implementation is faulty, and, for many reasons, voucher implementation is almost always doomed to fail. Trying to tie Marshall to vouchers is a political gambit, taking a hot-button issue at large — Donald Trump’s rather dim secretary of education is a fan of vouchers, and few in District 2 are fans of Donald Trump — and hoping it sticks to a candidate.

In terms of data, what Marshall does support is keeping the current teacher evaluation system, called TEI — as do I, and as does Schutze and other Marshall supporters. (A list, by the way, that includes known progressives like current trustee Miguel Solis, Dallas County Judge Clay Jenkins, and both opponents who ran against him in his past campaign, Suzanne Smith and Mita Havlik.)

I’m not going to completely re-litigate TEI. In part, that’s because I’ve covered a lot of this before. Here and here, for starters. In part, that’s because I don’t have to. The numbers do it for me.

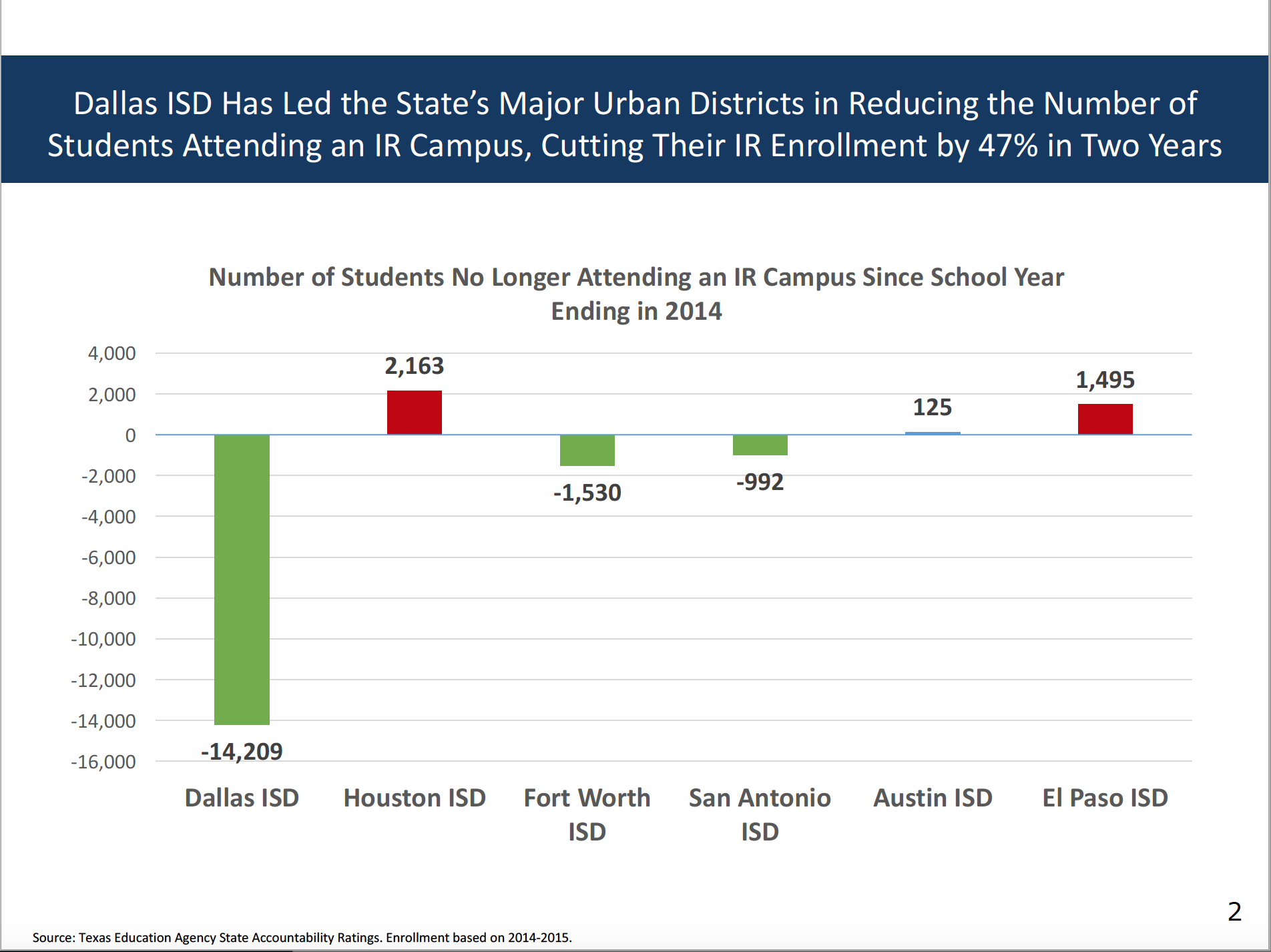

See that chart at the top of this post? That shows the number of students affected when seven of eight schools deemed IR (Improvement Required) by the state were moved off that list last year. Six of those seven were ACE (Accelerated Campus Excellence) schools. That means they took the district’s best teachers and placed them in front of the kids who needed them most. The results were staggeringly effective.

To make that program work, you have to correctly identify the best teachers in Dallas ISD. How do you do that? For 120 years — no, seriously, Dallas ISD’s seniority pay scale started in 1894 — the district used a calendar to determine which teachers were its best. Longest tenured? Best. It also used advanced degrees. As anyone who has ever worked in an office ever ever ever can tell you, while sometimes predictive of excellence, neither tenure nor advanced degrees directly correlate to excellence.

Once TEI was established, the district finally had a way to determine which teachers were its best, by multiple measures, including observation, student achievement, student surveys, and other data. Is it perfect? Of course not. But it is largely so. And because it has been continually improved, it is getting closer to perfect (or, at least, very good) all the time.

The most important way we can tell it’s working is monitoring student achievement, especially those kids that get in front of the best-rated teachers. It’s often said that the single greatest influence on a student’s achievement is teacher excellence — this is based on a flawed study, but let’s ignore that right now — and the ACE program showed that when it identified and rewarded (with bonuses) the best teachers to go teach the kids in the worst schools, the kids and their schools performed better across the board. That’s not simply good education policy; that’s the Lord’s work.

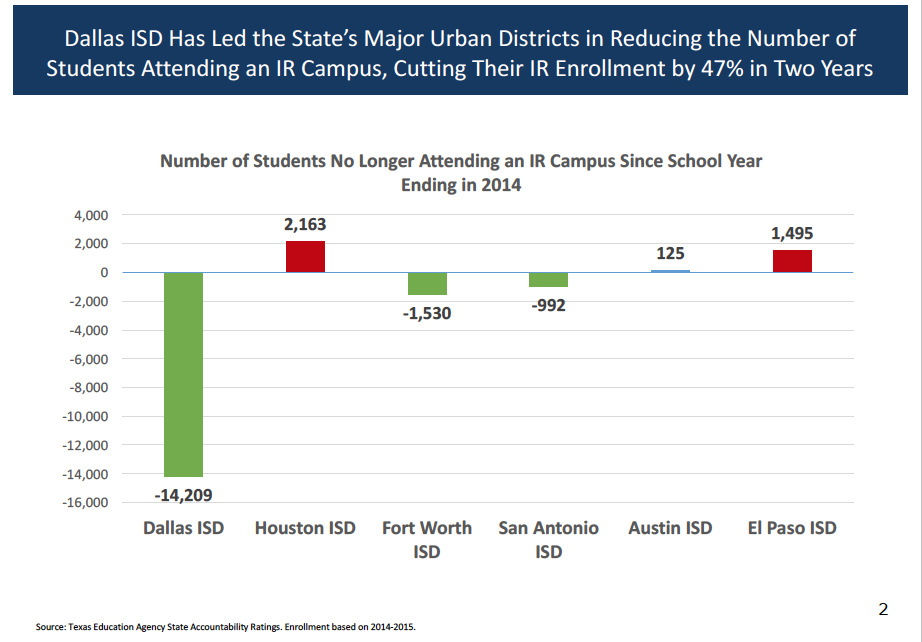

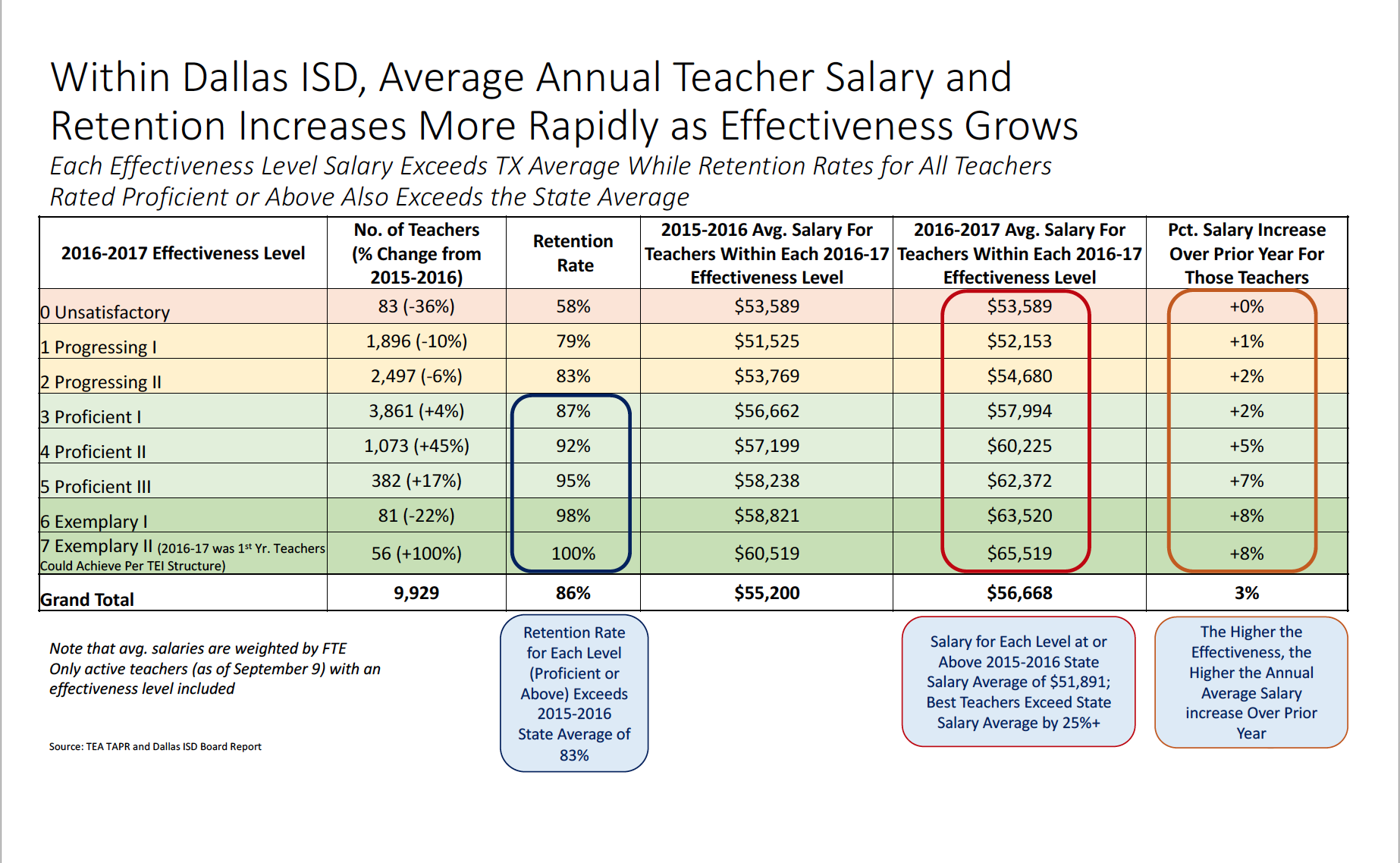

But has it been good for those teachers and the district as a whole? The following chart says yes:

This shows several important items. One, it shows a general bell curve distribution of excellence, which, as this research shows, is a feature, not a bug. Second, it shows that the vast majority of turnover is at the bottom end of the performance chart. That’s what you want: bad teachers leaving.

But as the great education writer Matthew Barnum points out, an effective evaluation system, one that improves student achievement, doesn’t only get rid of bad teachers — it also recruits and retains good teachers. This system is doing just that by rewarding not only its ACE teachers with bonuses, but as you can see, the best teachers are getting paid the most, and are seeing the largest salary increases. (The old saw that great teachers don’t want more money has been debunked many times over.) In fact, the idea that teachers disagree with the central tenant of this system is hogwash. They want tweaks, yes. But what percentage of teachers in the most recent DISD survey disagreed with the statement “My salary should be based on how effective I am as an instructor”? Less than 15 percent.

That’s the outline of the data reason that Marshall must stay. His opponent would certainly vote to get rid of this system and doesn’t have a better one in mind. That would be terrible for kids.

Despite this stark reality, a lot of progressives ignore positive data that comes from reform measures like this and buy into the narrative that all education reform — and especially teacher evaluation — is bad. Usually, they add that reform is part of some nefarious scheme being conducted by rich people who are trying to “monetize children.” (A quick digression. This isn’t true, but let’s say it is. So what?! That simply means they are trying to educate a workforce that needs to populate the disproportionate number of high-skill, analytical and emotional jobs that are being created so they can eventually make money off them. I’m okay with that!)

Why do they do that? A few reasons. One, Democrats make this mistake nationally, and they often misrepresent the data in doing so. The last Democratic platform said: “We oppose … the use of student test scores in teacher and principal evaluations, a practice which has been repeatedly rejected by researchers.” This is patently untrue. Leading researchers and economists in this area all acknowledge pitfalls in designing teacher evaluation programs, but nearly all of them — Matthew Kraft at Brown, Kirabo Jackson at Northwestern, Katharine Strunk at USC, on and on — say value-added measures in an evaluation system, while imperfect, can provide valuable data related to teacher effect on student achievement. In fact, progressive bias against such reforms is why there was a need to form Democrats for Education Reform.

As Schutze sort of asked: why doesn’t a data-driven discussion like this change anyone’s mind? Two reasons, I think.

One is obvious: we don’t change our minds because we don’t want to. Our self-identity is formed by our opinions, and our opinions must fall in line with our politics, lest our sense of self-worth collapse. We’re emotionally invested in being right. And the smarter you are, the better you’ll be able to rationalize and self-deceive. Progressives are really invested in believing that (1) a group is (2) acting in secret (3) to alter institutions, usurp power, hide truth, or gain utility (4) at the expense of the common good. (The four parts of a conspiracy theory.) I’m now part of the conspiracy, you see. That will be the narrative. Not only because of confirmation bias — that people only seek out information with which they agree. But because of something even worse: desirability bias — the “tendency to credit information you want to believe.”

The other reason people don’t change their minds in education issues is because they evaluate school issues through the same lens they do other political considerations. As I wrote three years ago, you can’t evaluate school trustees and city council members the same way. You can love your rabble-rousing councilman — and I often do — because you believe, in the big messy fight for competing values around the horseshoe, you need a stubborn voice railing against the powers that be. You might think — and I often do — that this gives you the best chance for a city that values its citizens over its institutions.

But schools are different. *I* matter only to a point. *You* matter only to a point. The difference is that school districts have one clear, overriding value that should govern every decision: effective educational outcomes for kids. That is all that matters. Better outcomes for kids trumps everything.

This is a really tough concept to get your head around, even though everyone thinks that’s what they’re arguing about. But if you show people objectively that kids who need help are being helped by TEI, they inevitably fall back on arguments that aren’t about kids. “I don’t want to support Republicans [reformers] in this environment.” “I want teachers to be happy [despite evidence they are more so than ever, in the aggregate].” Sorry. All those arguments lose.

As cheesy as it sounds, that’s what you’re voting for, here. You’re not voting for a teacher evaluation system. You’re voting for kids. Beyond that, you’re voting to be part of something bigger than you. You’re voting to support, to be a part of, a movement of caring, hard-working people of all stripes who have changed education for the better in Dallas. You’re voting to join the ranks of a growing army of people willing to stand up to others with whom they usually agree and say, on this issue, enough is enough. I say I love my city, but if I really do, I’ll make a stand so the kids who need my political influence will better learn how to read, write, and do math. You will say I believe in them, I believe in math, I believe in data, I believe in research, and I believe in science. You will ask of yourself what we ask of them: be brave, be smart, do the right thing.