Last week, Dallas ISD released a draft report to the media and the public the same day it presented said report to a 27-person task force. The district calls it its “Comprehensive Plan.” It is an incredibly important document, one that has been in the works for a long time, one that we foreshadowed on Learning Curve back in August, calling it the “story of the school year.”

You didn’t read about this report in the Dallas Morning News‘s news pages, even though it was released to the paper. (It was mentioned at the end of an editorial, because actually covering big-picture education is left to the paper’s opinion writers, because hell if I know why.) You see, as the paper told the district, “We’re too busy trying to get Mike Miles fired.” (Quote may not be 100 percent accurate.) This is understandable. The paper only has two education editors and four education reporters out of a news staff of more than 300. They have important work to do, like filing open records requests to see any and all communications between myself or Jim Schutze and the district. (Yes, that’s true.)

So, let’s try to catch you up on what is, without question, the most important story going on in DISD right now, one that will affect our poorest kids for decades to come. Because soon we’re going to have a conversation about this effort as a city, as concerned citizens, as parents, as taxpayers. And you need to do this extra reading on your own time, because the DMN is a little too busy polishing its rock of truth to bring you this information.

Here is the document that DISD released and used to brief its Future Facilities Task Force. As we discussed back in August, the plan suggests that we invest heavily in three key areas: early childhood, school choice, and career and technical education, or CTE. In August I suggested that this effort would cost $1.3 billion, and that it would have to be funded by taxpayers’ approving a TRE, or Tax Ratification Election bond. I was wrong: DISD says it will cost $1.5 billion.

That is a big ask, especially to the average taxpayer who reads in the media only about relatively meaningless HR scandals and not about complicated efforts to transform this huge poor urban district. So for you Learning Curve readers, who must act as sensible thought leaders in a sea of ignorance, let’s talk about what this plan is asking for and why it’s important.

We’ve talked a lot about early education, and I’ve written about it for D Magazine. I suggest you at the very least read that story if you haven’t, but here is an important excerpt:

When I met last summer with DISD’s early education chief, Alan Cohen, he showed me how massive was the task before him. He opened an Excel spreadsheet that accounted for each pre-K classroom in DISD. For each one, there were 60 items that needed to be checked off before he could declare it a “quality” pre-K environment. They still aren’t all checked off, but they’re a lot closer than they were a few months ago. With that progress made, he went before the school board in November and presented a six-year plan to increase the quality, size, and scope of DISD’s pre-K offering.

How important is it that taxpayers fund this plan? The DISD numbers Cohen threw out speak for themselves and are even worse than the ones in Dallas County as a whole. Only 38 percent of DISD kids start kindergarten ready. It’s vital that DISD increase that percentage substantially, because even though its pre-K program still needs work, a student who attends a DISD pre-K program is still 350 percent more likely to be kindergarten-ready than one who doesn’t.

Why not just make pre-K mandatory? For one thing, there isn’t enough capacity. If all the eligible kids living in the district (meaning poor kids) showed up for their pre-K classes, 2,700 students would not have a seat, because facilities aren’t geographically aligned with need. DISD leaves $60 million in state funds on the table every year, because it doesn’t have space aligned with need. So just as the district needs to fix its infrastructure to offer every child a seat, it also needs to increase the quality of instruction so that the money spent is more likely to show results.

Got that? It’s vital that the programs are of high quality, or they won’t succeed. And we must find facilities to align with where the kids are. (Example: There are 160,000 kids or so in DISD, but they are disproportionately south of I-30: 97,000, by my count. This is where the poorer kids are, and where we need quality pre-K the most, because it helps poor kids more than it helps other kids. But our pre-K facilities don’t match that demographic fact — nor do they match the projections of where the kids will be coming from in five years.)

All that takes money. Without question, early education is worth the cost. We’ve made that argument and will continue to do so.

Now, what about school choice? I had a talk with Miles about school choice, but it deserves a more in-depth discussion than we can give it in this post. So read the Q&A for background, but here’s a snippet to help you understand what this is [this is a Miles quote]:

We’re looking to have 35 such choice schools [by 2020] – not charter schools or private schools; Dallas ISD public schools. One choice might be a Montessori school. Another choice might be an IB elementary or IB middle school. But another choice could be another all-male school like Barack Obama, or an all-girls school like Irma Rangel. It could be an arts school like Booker T. If we can provide these options to kids – which also means transporting them – I think we’ll find we meet the needs of students and families better. More access, more choice, to more kids.

Before we go more in-depth on this, I need to meet with the head of this effort for DISD, so I know what the hell I”m talking about on a deeper level. Because there are a lot of smart, education-savvy folks (like Louisa Meyer) who have been bending my ear saying that school choice is fool’s gold — that it doesn’t understand the importance and value of a neighborhood school approach to reform. (I’m not sold on that, but I’m willing to air this discussion.) So let me just give you the basics. From the report:

Students in Dallas ISD currently exercise choice through a number of mechanisms. In 2013-14, 19,4021 students transferred away from their zoned school to another Dallas ISD school by choice: 10,286 exercised a magnet transfer, 6,959 exercised a hardship transfer, and the remaining 2,157 exercised parent public school choice through No Child Left Behind, Public Education Grant transfers, etc.

Although 12 percent of the student population are exercising choice, the current system of choice has inequities:

- Magnet school admission criterion preclude some students from accessing a desired instructional program,

- Magnet school admission and enrollment do not reflect districtwide student demographics (among students admitted to a magnet program for 2013-14, 59% were Latino, 19% were black, 12% were white; districtwide, 70% of students are Latino, 24% are black, 5% are white),

- Demand exceeds capacity in the 20 highest-enrollment programs (72% of applicants to the 20 most popular programs were either denied admission or placed on a waitlist for 2013- 14), and

- Only 34 students took advantage of a PEG transfer in 2013-14, although there were 35 Dallas ISD campuses on the 2013-14 PEG list.

As Dallas ISD seeks to ensure all students graduate from high school ready for college and career, Public School Choice will be a mechanism for growing the range of options so that all Dallas ISD students can attend a best-fit school. These are schools where educators more meaningfully and deeply engage students intellectually by tapping into their specific interests, aspirations, preferred learning styles, personal circumstances, and values. In this sense, choice can be a game-changer for many, many students. It can change the lens through which they look at their own education.

Maybe, maybe not. But it’s worth serious discussion as a city, don’t you think?

(UPDATE: I just noticed that Schutze talked about this today on Unfair Park. He focuses a lot on the choice aspect. So, when you’re done, go read that.)

The third element of this has been woefully overlooked. By me, I mean. I really haven’t understood CTE. Honestly, I thought it meant various kinds of shop or vo-tech training, the kind of stuff I had in the late ’70s in public school.

It’s embarrassing how wrong I was. This CTE stuff is huge, folks. It’s vital. It’s everything. Yes, it’s about providing education and training to people for real-world jobs. But that undersells its importance. What this effort is about is changing the way district employees — and, by extension, parents and citizens — think about the goal of a public education. “The end goal,” says DISD College and Career Readiness Executive Director Linda Johnson, “is not that we get kids through K-12. It’s not college readiness. It’s not even college completion. It’s the ability to earn a living wage.”

Think about that: It resets the expectations for everyone in a large urban district, from trying to meet state requirements for this test or that metric and just says “prepare these kids to earn a decent freaking living.” Inherent in that thought are several radical components, at least within the public education realm. One: That a college degree may OR MAY NOT be the best path for a student. Two: That your success will be measured not by what academia says of a child’s performance but by what the job market says of it. And so forth.

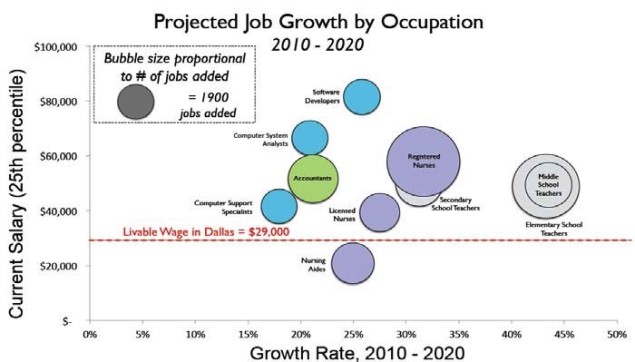

This effort does many things, not the least of which is aligning areas of training and certification with the regional job market/needs and career prospects. See this chart below for an example:

What this shows is the industries and jobs that are a) growing the fastest in this area, and b) what sort of wage (above the living wage line) they typically provide. DISD is using this to help make sure they are offering training and certifications in these areas that will help graduates get jobs — not just in lieu of higher education, but also in conjunction with their needs to pay for higher ed options (be they work training, associates degrees, or typical four-year paths) as they go, and from their own pocket. That’s why DISD offers a lot of certifications in health and safety, for everything from Patient Care Technicians to Pharmacy Techs to Dental Assistants to Nurse Aids.

As with everything in urban education, these efforts are expensive — and more complicated than I’m suggesting. (A lot of this CTE alignment, for example, has to do with requirements of House Bill 5, passed in the last session. If you want details, sorry, I’ve already forgotten them.) But, when combined with the promise of early education and school choice, I think this is a transformative plan worthy of discussion until we eventually vote on whether we’re going to step up and fund it as a city.

DISD thinks so, too. They’re trying to learn how to better involve communities in their long-range planning — a huge weak spot to-date — and they’ve labeled this plan a “draft” document for that very reason. Before taking a $1.5 billion ask to voters, they want community input: Does this align with want your school system to look like in 2020 and beyond? As I said, it’s vital we have that discussion, starting today.