When I worked for a large corporation, I knew a guy we’ll call Frank. Frank wasn’t fond of his boss, Larry, because Larry was kind of a jerk. One day, when Frank was in the office of Larry’s boss, working on a project, Larry’s boss asked Frank, “How are things going on your team? Any feedback I need to hear?”

What did Frank say?

Frank is not an idiot, so Frank said, “Everything’s great.” Because only an idiot would unload about Larry to the big boss. No big boss really wants to hear from someone several levels down, “Hey, you know that person you hired to oversee me? The person you’re friends with? The person you promoted? TERRIBLE CHOICE. Fix it.” Once you say such a thing, it can’t be unsaid — you’re marked as a troublemaker, you have to go through some weird HR-led confrontation/counseling, all when it’s the job of the top brass to know how Larry is doing in the first place.

This dynamic exists in every large organization. It certainly exists in Dallas ISD when it comes to getting feedback from teachers, especially if that feedback would necessarily throw principals or executive directors under the bus. It exists especially when trying to get feedback on the implementation of the district’s teacher merit pay evaluation system, TEI (Teacher Excellence Initiative).

It’s why Dallas ISD brass, even though they’re getting feedback from teachers on said implementation, aren’t always hearing the full story. So I’m going to give some feedback on behalf of many teachers who’ve expressed concerns, either to me directly or to administrators with whom I spoke — complaints that center on one important component of the plan.

Understand, this is not one of a million gripes from the Dallas Frenemies of Public Education or other people who make their living tearing down the house in which they live. I talked to teachers who welcome TEI, who are excited about the chance to be duly compensated for the outstanding work they do, and who believe such a plan will help get rid of the few burned-out, terrible teachers who make everyone’s job harder. These are people who want it to work but who are frustrated with TEI’s implementation, especially with one portion of it: SLOs, or Student Learning Objectives. The district believes that it has implemented a smart, sensible model that largely eliminated the merit-pay-system mistakes of other districts. Fair enough, and I would agree — in theory. But it’s important for DISD to see how screwing up one element of the plan is undermining confidence in the entire program.

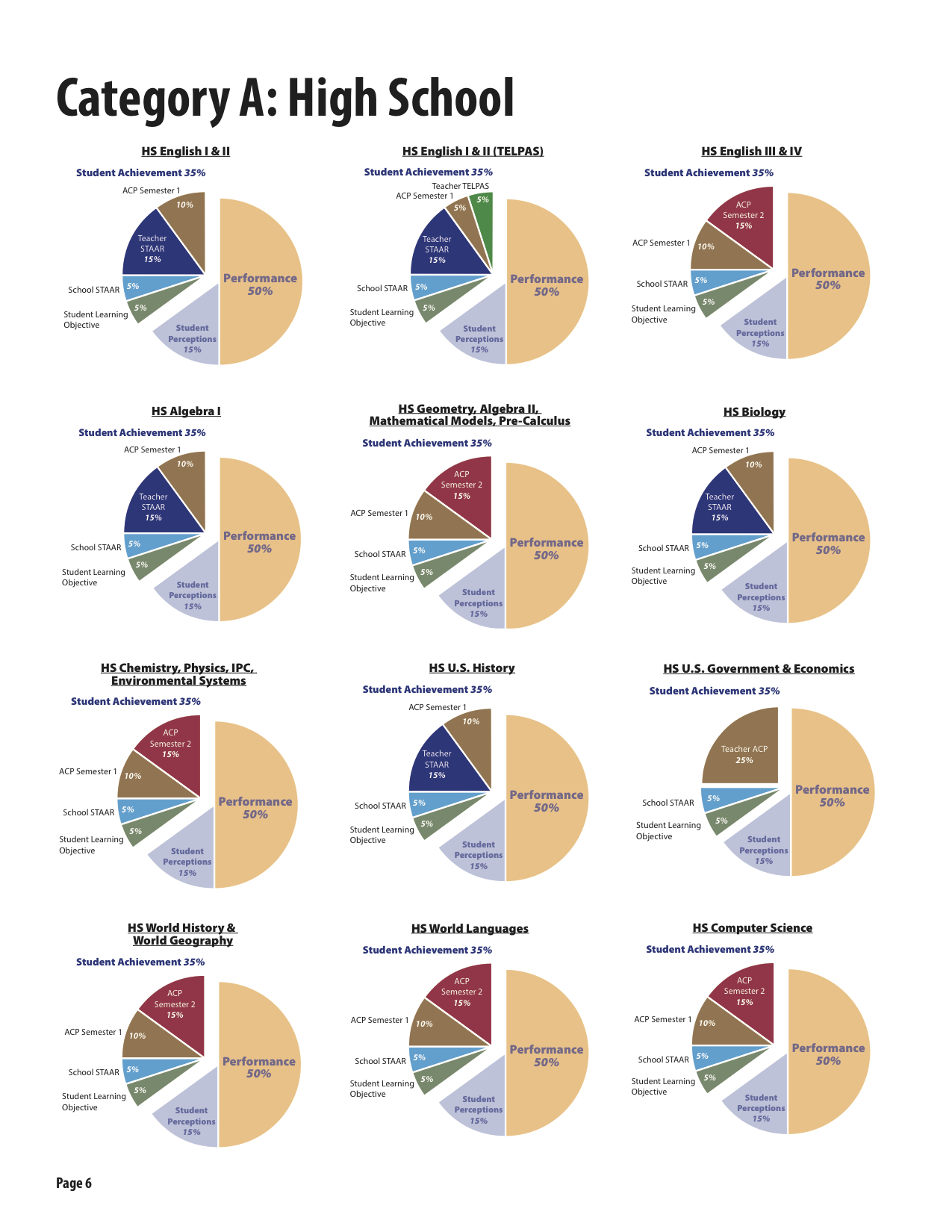

First, we need to recall how TEI works, and by that I mean, what determines a teacher’s evaluation score. The image at the top of this post shows a few of the breakdowns for different types of teachers in DISD, and there are many more. (All this information can be found on the district’s TEI page.) In most cases, 50 percent of a teacher’s grade is based on observed performance (done by spot checks); 35 percent is student achievement data, and 15 percent is from student evaluation. There are many variables within each of those categories, but let’s focus for now on the 35 percent that is derived from student achievement. As you can see from the chart above, and if you look at all the teacher-type breakdowns, you’ll notice that in most cases, SLOs count for 5 percent of a teacher’s overall score. That score is tied to their review and compensation, so every point is important.

What is an SLO? A Student Learning Objective is just what it sounds like: It’s a teacher-constructed, administrator-approved plan to define and measure student outcomes. It’s the sort of thing many people in many companies have to do: You’re given a project and an end goal (in this case, raise student outcomes). Now, let’s define our goal more clearly, by establishing exactly what we can measure, where students are today along that measurement, and where they need to be at semester’s end. This is standard project-based, scope-of-work definition that every company (outside of most journalism companies, where they too often see their work as more alchemy than business) goes through. That teachers are only in the past few years being required to do this is nuts, and it speaks to the way we still too-often view public education as a mix of magic and 19th-century classroom-instruction techniques. The idea of doing this is not new — Denver is considered the leader in the SLO movement, and it began looking at this back in 1999, and of course teachers have been informally setting goals for decades — but its acceptance as a necessary component of teacher evaluation is relatively new. (By the way, here’s a great story in the Denver Post about the district’s current teacher evaluation system. It has loads of context, very even-handed. It’s really spectacular.) That’s why districts all over the country — in 30 states, according to DISD — are implementing SLOs as a part of their teacher evaluation systems. That’s because of the result of the Denver SLO implementation, summarized on page 5 in this U.S. Department of Education report:

Teachers who developed high-quality SLOs produced better student-achievement gains, and student achievement increased as the length of teacher participation in the pilot increased.

Sounds good, right? That’s why the architects of TEI wanted to ensure they included SLOs in the final scoring system. (Contrary to what many teachers believe, the SLO portion of the did not spring from nowhere last May when the plan was approved by the DISD board. It has been part of the discussion the past two years and was included in the district’s beta testing, but it was then called an “individual teacher goal.”)

The concerns begin there. The biggest problems with its implementation are the following:

1. The entire SLO process is too time-consuming for something that only counts 5 percent of a teacher’s score.

2. The SLO communication between the district and teachers has been, at best, lacking (at worst, pitiful).

3. Numbers 1 and 2 combined feed fears about the administration’s ability to correctly implement substantive change that rewards the best teachers and punishes terrible ones.

4. Numbers 1, 2, and 3 combine to make the long-range goal of identifying, rewarding, and retaining the best teachers — and, in turn, attracting great teachers from outside the district — just that much more difficult.

Let’s take these one at a time:

NO. 1:

Teachers were told from almost the first day of school that they were to spend most of September creating their SLO plans, which would then be reviewed by various administrators above them. Again, this sounds reasonable. But as teachers received their instructions, and tried to incorporate developing this plan (let alone contemplate the actual grading/tracking/etc. that goes into actually following said plan), I started to hear off the record rumblings that this was, to use one phrase I heard more than once, “a deal breaker.”

The problem was that this program was simply added onto the many other elements teachers are already struggling to implement under Miles’ reforms (the majority of which, remember, I am a fan). So, using one English teacher’s example, the SLO benchmark/pre-test and post-test and weekly grading for all students and review from school/staff administrators gets added to the STAAR benchmark/pre-test and the ACP writing benchmark and the ACP test in December and the STAAR benchmark in spring and the STAAR test and the Writing Assessment of Course Progress test oh right and the AP exams and others that I don’t understand and don’t want to take the time to learn about.

This meant that, for much of September, even those teachers who are very much onboard with Miles’ plans felt overwhelmed to the point they just can’t keep up with the demands, no matter how many hours they put in at home or on weekends.

Huge sub-point here: That level of frustration was felt on behalf of something that only counts 5 percent of their final score. (Sometimes 10 percent, but most of the time 5.) I spent a lot of time looking at evaluation systems across the country that formally incorporate SLOs, and almost all of them counted the SLO grades as a substantially higher percentage, clearly recognizing the work involved. (Usually it’s somewhere from 20 to 35 percent of your grade, the same range as it is for example in Pennsylvania and Maryland.)

DISD, in response to several specific questions I asked about SLO implementation, said that it’s misleading to focus on the fact that this work only counts toward 5 percent of a teacher’s score, because a properly executed SLO will help student achievement across the board (as the Denver results suggested), and student achievement makes up 35 percent of a teacher’s score. From the DISD response:

While the SLO itself is either 5 percent or 10 percent of a teacher’s overall evaluation score, the impact of a strong SLO will be reflected in all of a teacher’s student achievement data.

Well, okay, sure. And good teaching will be reflected in student evaluations, and in your spot obs, and it’s all one big feedback loop of awesomeness. But that doesn’t address the fact that good-to-great teachers who already feel overwhelmed now feel incredibly so.

“SLO will put the nail in the coffin for many teachers,” one recognized teacher told me. “It’s so complicated, yet only 5 percent of the pie. Many will say I’m not going to do it. … Yes, it’s reasonable and logical [on its own]. But when you ADD it on top of other changes, it feels like … a deal-breaker.”

In fact, what you have are teachers making a very reasonable cost-benefit analysis: is this huge truckload of work worth my attention if it’s only going to hurt my ability to do my job otherwise, and only counts 5 percent? I know of principals/asst. principals who have all but acknowledged this dilemma and told teachers it’s basically up to them to decide how much they put into it. This is a huge problem, and one that should be discussed as they look to re-evaluating SLOs in the context of TEI as a whole.

NO. 2:

The district seems pretty defensive that teachers weren’t given enough time to understand the SLO requirements before they were added onto teachers’ collective plate. When I asked if teachers were only given the half-day of SLO training during the first week of school, this was the response:

Teachers who participated in the achievement template focus groups in June 2013 were introduced to this component. All teachers were introduced to the component at a high level through campus presentations conducted by their Assistant Superintendent during the fall/winter 2013. All teachers also received an update on the design of TEI by colleagues who were trained to deliver this information in the spring 2013. This TEI update also reflected SLO information. In addition, we beta tested the SLO component with 175 teachers across 25 campuses during the 2013-14 school year. The feedback from these teachers informed the training needs for SLOs that was provided in August.

That sounds like a lot of SLO instruction. But if you parse it, two things become clear: one, I believe the district is confusing careful communication with a small group of teachers (for example, the 175 of more than 10,000 teachers); and two, they’re also relying on a network of people to communicate this to already over-burdened teachers who are going to have varying levels of understanding and buy-in to this process. And that’s what I’ve been hearing from teachers.

“It’s all about who is communicating this to teachers, and that varies widely by school,” said another teacher who has been in contact with dozens of frustrated teachers. “The materials are confusing, the process is confusing, the deadline dates keep changing. Now, at some schools, there’s no problem. But good teachers at schools where this is not being met with appropriate, conscientious oversight? Those teachers are really suffering. This is definitely a problem.”

Have a look at these documents, sent to teachers by their school’s TEI reps early in the semester. SLO Part 1 is a DISD-generated doc that outlines what an SLO is and should be. SLO Part 2 is a doc generated by the SLO vendor, the Community Training and Assistance Center (the same group, btw, who touted the results of the Denver model cited by the DOE … but I digress). Read those, then answer these three questions for me:

- Why haven’t school documents improved in the past 50 years? Seriously. They all still look like they are mimeographed sheets shown on an overhead projector. And it’s not just DISD. Good lord, look at that Maryland PowerPoint I linked to above. It’s like it’s made by a mid-level manager at IBM circa 1997.

- You tell me if that’s all clear as mud.

- Do you think that a teacher could add such a process to an already full schedule, and, if they somehow did and maintained their quality, do you think it should only be reflected in 5 percent of their score?

Personally, after many, many conversations about this with teachers and board members and administrators the past several weeks, I’m convinced this is at its heart a communication problem. Let me give you a small example: I was on the phone with a teacher who, while we were talking, pulled up the SLO_Template-Worksheet on the district’s TEI site. She and I were astonished to see that it said that all SLOs must be entered into the district’s system by October 31 — when everyone was scrambling to finish by Oct. 1 (and, in some cases, a week later if you said teachers were given an extension). This teacher had no idea the date had been changed. I asked DISD, which responded:

All goal-setting conferences need to take place by October 1st. During these conferences, teachers and administrators discuss SLOs and professional development plans for the year. October 31st is the date by which all SLOs must be entered into Schoolnet and scored by administrators using a standardized SLO rubric. The SLO worksheet that was posted last Monday is intended to be a resource for a small number of teachers who were having difficulty with their Schoolnet account and could not enter it via the online platform. These teachers are able to use this template to draft their SLO before entering it into Schoolnet once any outstanding issues with their account are resolved.

I can tell you that this was news to a lot of people.

No. 3:

This one’s pretty obvious. Change this massive brings about many fears, some legitimate, some not. But when you’re trying to sell so many elements of a reform plan, the core portions of your teacher evaluation system must be clearly explained to everyone participating, every single day. It’s vital. If you lose teachers on this, you lose them on so much more.

DISD says it recognizes this. Here is the district’s statement, which basically says, “Hey, it gets better, promise”:

We recognize that SLOs are a new element for our teachers, our principals and our students. Past districts’ experience in implementing SLOs has shown that the process does become easier with time. On the one hand, thus far, we have heard appreciation for SLOs from teachers and administrators as the SLO development process has help create both focus and collaboration in ways that did not exist before. At the same time, we have heard questions about SLOs and the specifics of the process, and often for very specific teaching circumstances. For this reason, the time commitment involved for teachers will vary the first time they create an SLO. For some grade-level or course teams that have developed team goal-setting processes as well as a pre- and post-assessment in the past as part of their professional learning community, the SLO process requires little additional effort. For other teachers, this process will indeed be new and may require extra time in September to establish a useful SLO.

Woof. I get that this is one of those “we’re raising the bar, everyone has to jump higher” statements. In theory, I am 100 percent behind that. We need to demand more from the district, we need better educational outcomes for kids, and that starts with defining and measuring success. But I’ve got to say that I’m with the teachers on this one: It’s not being integrated appropriately, both in terms of how it meshes with the other work already required, and in terms of its weight in the overall score. And that leads to big problems …

NO. 4:

In terms of retaining and attracting the best talent, the district has to get this right. I know Miles and other say that TEI is a “continuous improvement model,” but that doesn’t mean you have to wait a year to tell teachers you’re hearing their concerns. Give monthly updates, hold more forums (in which teachers can anonymously give examples and concerns), because this is not just disgruntled frenemies arguing about their latest DISD complaint. This is something that is fixable, with better implementation, better communication, and better sharing among teachers about the feedback you’re already receiving. I really think that, if not addressed soon, SLO implementation could be the Achilles’ heel of TEI, and that would be damn shame.