Last week, I moderated a home rule discussion for the Dallas Assembly, a group that, best I can tell, meets once a month to have local geniuses moderate panels of interest. I was asked to begin the luncheon by putting the home rule discussion in context. I didn’t really do that, in the sense that I didn’t put our particular home rule discussion in context. But I did try to put the idea of governance reform in context, and I did so by leading with an important recent study that suggested superintendents don’t matter to student outcomes.

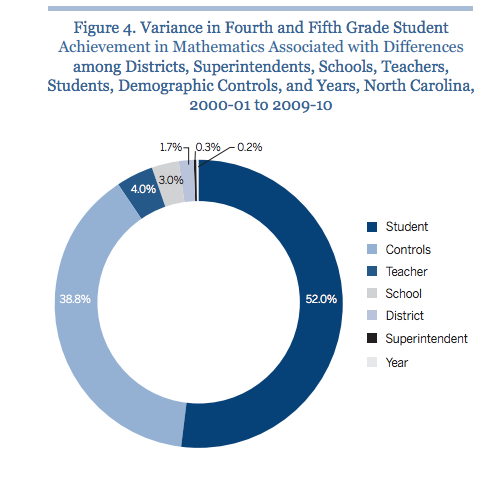

You may have heard about the study — by the Brown Center for Education Policy at the Brookings Institute — on an NPR report titled “The Myth of the Superstar Superintendent.” It found that superintendents had almost no effect — .03 percent, actually, as shown on that chart at the top of this post — on student outcomes.

You really should read the study, because it’s fascinating. The takeaway for those focusing on the superstar superintendent angle was obvious: You shouldn’t waste time scouring the country and paying high salaries to big-name supers, because they don’t ultimately make a difference in student outcomes. (The only thing that should matter, at the end of the day.) From the exec summary:

Superintendents whose tenure is associated with sizable, statistically reliable changes in student achievement in the district in which they serve, controlling for the many other factors that affect student achievement, are quite rare. When district academic achievement improves or deteriorates, the superintendent is likely to be playing a part in an ensemble performance in which the superintendent’s role could be filled successfully by many others. In the end, it is the system that promotes or hinders student achievement. Superintendents are largely indistinguishable.

It’s understandable that this is what made the news: After all, the point of the study was to determine if a quality superintendent helps outcomes. (For comparison, it’s pretty well established that a quality teacher adds value to student outcomes.) And this of course made nervous some people whose job it is to find good superintendents. New Orleans and Baton Rouge, for example, are currently looking at superintendent candidates. (Nola.com provided a good online discussion between a study author and the a few of the study’s detractors.)

But there are three things we should note about this study, and how it affects our home rule debate, as well as the debate about education reform in Dallas in general:

1. The study actually suggests that the entire school system itself only kinda matters in relation to student outcomes.

2. The study also suggests that our current public educational systems — still largely based on 19th-century models — have very little chance to greatly change student outcomes — so perhaps the entire ecosystem itself needs rethinking?

3. The study might not hold up under scrutiny.

As I told the audience last week, I’m less concerned about what that chart at the top of the page shows about how ineffectual school superintendents are and more worried that it suggests entire school ecosystems are largely ineffective. Simplifying this study to an almost unrecognizable state — hey, that’s the way media go — it says that 52 percent of a student’s outcomes are determined by the student, i.e., who and what the kid is. That feels about right, in our gut, doesn’t it? But then it says that nearly 39 percent is “control,” which is a proxy for things like race/ethnicity, which can also be seen as a proxy for poverty. So if a kid is white and wealthy, that accounts for nearly 40 percent of the outcome, as does if the kid is minority and poor. (Of course, every variable in between, as well.) That means that teachers (4 percent), schools/principals (3 percent), and districts/supers (2 percent) only move the needle 9 percent in terms of determining a student’s outcomes.

If true, this means several things. One, as I told the audience, that means that if you are spending a ton of money to send your kids to private school, you are largely wasting it. Your kid wouldn’t do even 10 percent worse on average in a poor school system. It could also mean, though, that given the slim chance to make a real difference, large poor urban districts are even more important than we thought. Because that 9 percent swing in outcomes with a rich white kid might mean he/she gets her act together in 9th grade instead of 12th. But for a poor kid who faces huge challenges every day, those small tipping points matter. Nine percent swings can mean the difference between a failing or passing grade; a diploma or dropping out; college acceptance vs rejection.

To me, it also means we should make our city leadership MORE involved, not less involved. We already know poverty/culture/race is a huge factor in education; when the city is responsible for providing an acceptable level of opportunity to combat poverty, then they should have a stake in the education system that is so greatly affected by a city’s attempts at reducing poverty. That’s a whole other post, though, one that you should prep for by doing a little research — how many large urban districts have, in the past 20 years, switched to at least a partial mayoral-control school system? (And how many are now contemplating doing the same thing?)

But if this study is true, should the only question be, How do we optimize that 9 percent? Shouldn’t we also ask ourselves, Can we create a system that has an even greater impact on student outcomes than our current one?

To me, that’s what this home rule discussion is about. Are there models out there that are so transformative, they are worth trying to adapt to our troubled, large poor urban district? Is there a way to adapt what something like District Four, in East Harlem, did with 14,000 poor minority students and adapt it to a system with 169,000 kids? This centered on school choice, which Mike Miles is addressing, albeit in not such a radical way. (That District Four was affecting student outcomes by A LOT more than 9 percent, no question.) I think this study suggests we look at wildly transformative models like the Portfolio model used in New Orleans if we are going to create systems that have an effect on outcomes anywhere near on par with poverty or the makeup of the kid him/herself.

But, as I say in point No. 3, although I think this debate is meaningful, the study may not hold up well. There is a very reasoned, very methodical deconstruction of its methodology here that suggests superintendents are far more influential on outcomes than the Brookings study suggests. Pat Burk is an associate professor in the Department of Educational Leadership and Policy in the Graduate School of Education at Portland State University, and he’s not impressed with the study. Read the whole post, but here are the choice excerpts:

This is methodologically weak in that no attempt is made to identify specific actions of superintendents that did or did not contribute to the positive effects of the teachers, principals, schools and districts that the report highlights. By not asking the right questions, the study draws a conclusion, i.e., superintendents don’t matter, without actually collecting and reporting information on any actions taken by superintendents.

They attribute only 0.3% of the explained variance in test data to differences in the superintendent. However, the majority of the variance is being attributed to unmeasured variables assuming that the unmeasured variables have nothing to do with the superintendent. Is it not possible that the Brown Center report simply did not ask the right questions? For example, a superintendent may exert leadership around issues of a race-based achievement gap and you would not, necessarily, see that influence attributed to the superintendent in this type of data collection. If parents become more engaged, if local community-based organizations become more collaborative partners, if teachers begin to focus on racial disparities in more effective ways, etc., this study would not attribute those differences to the superintendent because it did not ask that question. Attributing unmeasured variance under a “Student” category is misleading and likely inaccurate. At a minimum it reflects that many questions were left unasked in this analysis.

Burk closes by noting that the authors did not even mention the influential McREL study I’ve posted here several times, which shows a link between superintendent longevity and increased student outcomes. This seems important.

My conclusions, then? They are:

1. What is important is that we see the entire educational ecosystem as one thing, understanding that governance and administrative decisions filter down to teachers and schools, which can then pass right back up the chain. By definition, an ecosystem is complex, each element affecting other elements in many ways.

2. Nevertheless, we should try to find ways for that entire ecosystem to have more impact on student outcomes, and look to outlier success stories for inspiration.

3. You should never take as gospel media reports on a study that come out the same day the study is released. IJS.