Dana White recently become the first Black woman to launch a national franchise campaign for a hair salon. Her brand, Paralee Boyd, named for her grandmother, focuses on hair health and treatment for women of color, using hydrating and healthy ingredients and techniques. She launched her first salon in Detroit in 2012 and doubled to a second soon after but was forced to close during the pandemic, as the population density of the city’s downtown dwindled.

Now, she has launched a new, revamped flagship location in Arlington and is actively seeking franchisors to help grow the brand nationwide. She also has landed a global contract with the U.S. Military to open salons on military bases. The first of these will open in Fort Bragg early next year, and two more domestic Air Force bases are in the works. Others on army bases abroad will be coming soon after. “A year from now, my hope is to open one other location in North Texas,” White says, “then the goal is to go to Atlanta.”

Here, as part of D CEO’s My Reality series, she shares her struggles with blatant racism during her upbringing, throughout her career working for a labor rights organization in New York, and as she built out her salons.

Growing Up in a Stifled Environment

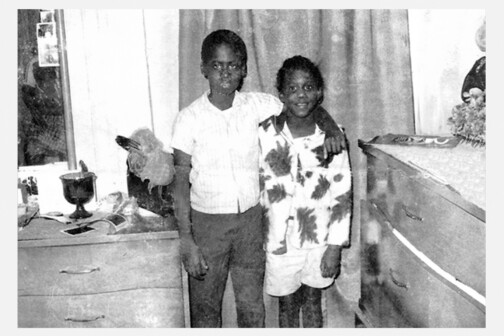

“I’m from a town called Kalamazoo in Michigan. It was your quintessential small town, but not too small. I went to a school called St. Monica, and I was one of maybe three or four Black kids. One of them was my brother, and he only stayed for a couple of years. He was in first grade when he left. I was in third grade. We found that he wasn’t learning and my parents couldn’t understand why. We found out the teacher refused to teach him and another young man, who also was Black. She made them sit in the back of the class, facing the wall, throughout most of first grade. They both had to do first grade over. [My parents] moved my brother to another school. I stayed because I was doing fairly well.

“Unfortunately, Kalamazoo just wasn’t equipped. If you look at my eighth-grade yearbook, there’s a picture of the principal’s daughter in her grandfather’s KKK uniform. We were all doing history reports, and we dressed up as the people we were doing the report on. She was doing the report about the KKK, and she came to school in her grandfather’s KKK outfit.

“I look back and I ask, ‘Mom, why was this OK?’ Our parents were taught that a White education is the right education; that it’s better than going to a deprived, predominantly Black public school system at the time. Kalamazoo County public schools aren’t bad, but they weren’t private schools. Private schools are a little bit better. The cost of that is racial issues.

“My father died suddenly of a heart attack when I was 11. I was having a hard time afterward and in class, I would just sit still at my desk. My teacher said ‘Dana, I need you to do your studies. I need you to work.’ I said, ‘I’m having a really hard time.’ She asked, ‘Why? Do you not understand it?’ I said ‘No, I do. But right now, I just miss my dad.’ She said ‘What did you expect? He was a [slur]. He was going to die.’ I’ll never forget it. This was not in 1943. This is not in 1968. This was 1988 or 1989 in a northern city.

“I went to high school in a suburb of Kalamazoo called Portage. They had ‘National Wigger Day,’ where some teachers and students dressed up in stereotypical Black urban garb—rags, pants sagging, hat backwards—and the teachers spoke the dialect they thought Black people spoke. Everybody would crack up. The kids would participate, and as a Black girl, I’m sitting there thinking ‘That’s not me.’ It was completely inappropriate.

“One time, a classmate said ‘Dana, you’re acting like a [slur].’ So I went and told the teacher and she said, ‘Well, were you acting like one?’ I called my mother. My mother came up to the high school and took me home. She said, ‘We’ve got to figure out what we’re going to do. I’m taking you out of school today.’ Then the story got out. The news media came to our house, and my mother did an interview.

“My mom got on the news and said, ‘I will protect my kids by any means necessary.’ That was around the MLK holiday. The neo-Nazis and White supremacists shot up our house and wanted us out. My mother was a police officer, so we had a lot of cop cars taking care of us, but that was the environment I grew up in.

“Had it not been for my parents teaching me how to process it without being a victim and without being angry, I wouldn’t be where I am now. It was an excellent character builder. I got an amazing education that has equipped me to this day to do what I do.”

Walking through Professional Challenges

“I went into the union organization seeing the disparity between leadership and members; seeing that members only got so far up; seeing that the people who were running it went to Ivy League schools, and they were all White. There are wonderful people who are working for the rights of people, but there are also people there who think it is a business like any other business, and it wasn’t always fair. I was awfully sexually harassed, and I left.

“For African-American women, getting our hair done has always been a challenge. You have to know the right stylists. All the moons have to line up perfectly. I got tired of that. I didn’t want it to be a challenge anymore. I thought ‘Why can’t we have a Great Clips for us? Why can’t we have a place where we can go to get a reasonably priced hairstyle that is catered to us?’

“I got a settlement from everything that went down with the sexual harassment, and I took a year to do as much work as I could on my salon concept. I moved back to Michigan in September 2012. I had a space ready to go, and it opened that November.

“Even while I was building up my location in Michigan, the contractors were all White male contractors. They said ‘Do you know when the owner will be here? We’re ready to start the meeting.’ I said ‘Yeah, I’m here. I can help you.’ They said, ‘Well, can you just call and find out when they’ll arrive?’

“I let them wait. Five more minutes passed, and they said, ‘OK, [the owner] is 10 minutes late. Are they normally late?’ I said, ‘I’m here. I can help you.’ They’re like, ‘Well, who are you?’ I said, ‘I’m the owner.’ They said, ‘Why didn’t you tell us you were the owner when we asked for the owner?’ I said, ‘Why did you assume I wasn’t the owner?’

“Because of where the salon was, they assumed that I was the person who worked for the owner. A lot of Black business owners let you think that they’re working on behalf of somebody White because you get treated differently. The White business owner that’s not at the meeting is more respected than the smart Black girl working for them. I have actually acted as if I were working on behalf of a nonexistent owner.

A New Beginning

“I love Texas because people meet you where you are. Here, if you’re a racist, you tend to stay away from people like me. You don’t have to exude your will or what you deem to be your power of racism. You don’t need me to validate your racism. In Michigan, it felt like people were thinking ‘I need you to know I’m a racist. I need you to know that I don’t want you here.’ I found it harder even from a customer service standpoint.

The idea of going above and beyond—I didn’t see that really in Michigan. Here, you can pull up to a Chick-fil-A, and they’ll see you and talk to you in the driver’s side window while they’re waiting on your order. I was in Home Depot last night returning something, and [the clerk] saw something on the receipt before I did. She tried to double and triple check it. I didn’t have to ask her to do it. People are doing the work that they want to do.”

Get the D CEO Newsletter

Author