Bruce Wood Dance Company’s season-opening concert, Spring is primal in the sense that it tackles head-on the act of creating and the complexities of human experience.

The program includes a Dallas Museum of Art-commissioned premiere, The Rite of Spring by Bruce Wood, and a commissioned premiere by lauded, Chicago-based choreographer Stephanie Martinez (founder of PARA.MAR Dance Theatre) as well as a repertory solo by Wood.The piece will be performed June 10-12 at Moody Performance Hall.

At a time when we are thirsty for the arts, the show creates a dense weave. It reminds us of the vulnerability we all share.

Chameleonic in nature, rippling with jewel tones, and utterly synaesthesic, “Slip Zone Suite” presents a first. Bruce Wood Dance artistic director Joy Bollinger was commissioned last fall to choreograph a work based on the exhibition (titled “Slip Zone”) on view at the Dallas Museum of Art. The exhibit is on view through July 10, 2022.

It was the first time she was inspired by such a source.

For Bollinger, “the richness and saturation of the colors” next to works of staunch minimalism introduced a question: “How to take that kind of visual and visceral range and connect it and structure it into a dance with a clear visual and structural and emotional arc. And that became the puzzle. That became the real puzzle.”

At just over 30 minutes, the result is a moving, complex suite–with projections to showcase the six works or sets of works that inspired it–that forms a study in color, and the longest piece she’s choreographed.

The DMA exhibit highlights works that span from abstract expressionism to color field painting to minimalism. Moved by the ways artists smashed bottles filled with paint or poured or smeared it onto surfaces or merely allowed a medium to be, Bollinger has created a movement vocabulary that subtly, beautifully captures and conveys the range.

The sextet suite begins with white on white, the dancers swaying ever so slightly, as though animated by the same breath. A frail synchronicity arises as they take pneumatic sips of air. The subtlety reflects the delicacy of the monochromatic works in fragile Korean rice paper and painted wood (by Kwon Young-woo and Sergio de Camargo) that inspired the tenuous responsiveness.

The simplest gestures–“crumble, crumble, crumble. Sit up, sit up, sit up”–are slight but strong enough to evoke a visceral feeling that surpasses form. “You take a breath and it sends a breath through the group,” Bollinger says of the opening, which is different every time.

As with minimalism, in the hands of these dancers, we brush against the ineffable.

The impression of floating, of gravity and weightlessness, continues in the second, solo section, in which the only costume is the ice-dyed swath of fabric that introduces a fluttering splash of color and mirrors Leaf by Sam Gilliam. It forms a drape which dancer Megan Storey clutches, disappears under, and reemerges from.

And so the slippage goes: A gorgeous duet brings in a symphony of reds and orange in a way that echoes and dialogues with Guyana-born Frank Bowling’s Marcia H Travels, the dancers mingle with lingering promenades in an exquisite pas de deux that has them melt into the color just as they do into each other.

Meanwhile in the fourth section, technicolor swirls form whirlpools and living topographies–as they do in Shozo Shimamoto’s Untitled, Whirlpool, and Kazuo Shiraga’s Shining Colors, the inspiration.

The dancers mound and pile, as though yearning to be seen from above, in a tour de force of lifts that crest like waves (and lead to a stunning solo by Jillyn Bryant and duet with Seth York).

Soloist Weaver Rhodes becomes a blob of paint that squiggles into view; it is riveting, not the least bit gimmicky. It comes to life against the projected depiction of Jackson Pollock’s abstract expressionist Cathedral, flitting and flinging itself into existence, just as, Bollinger notes, Pollock is known to have “danced” around the edges of his paintings to create them.

In the final section, the music crescendos to intense percussion as four male dancers throw colorful sleeves into the air and enact a series of rolls, virtuosic feats of timing and height–and the raw power of explosive color, transmuted into sound and form, triumphs.

This is, first of all, a profound effort of translation. Choreographically, it is also masterful, enticing, and engrossing, full of grace and control.

Bollinger had not thought, she says, about “color in movement before. Not in this exact way.”

“The last work I did was titled Blue, and we were talking about blue as a feeling and all that can be within that feeling. But this project has really drawn my focus to the feeling of color, more than ever. For my first few works [in her choreographic career], I would have been happy if my dancers wore gray: I was so interested in the bodies designing the space that I didn’t always feel that color was needed. This is probably the first time I’ve been so careful with when to introduce color in a dance, what that means,” visually and emotionally.

Ultimately, she says of the dialogue between choreography and inspiration: “I did what it made me feel.”

“Slip Zone Suite” is sensitive and vulnerable. But Martinez’s “When the Sky Fell Purple” brings us to other brinks. Based on her grieving of her mother, who passed away in the last year, the work is intended for a company that can deftly handle the most human of material.

Martinez herself has choreographed for companies including Joffrey Ballet, Ballet Hispánico, and Luna Negra Dance Theater.

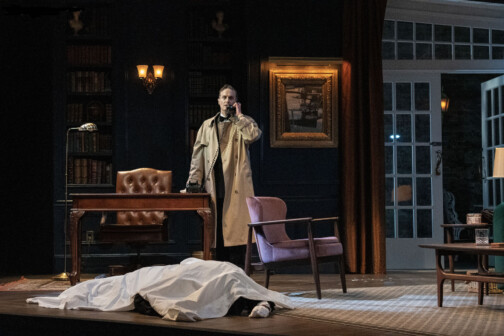

Finally, the avant-garde reenters in another guise at the end of the program in Wood’s The Rite of Spring. Wood’s version has not been performed since its premiere 20 years ago, in April 2002, when the company was still based in Fort Worth. But it feels as stirringly experimental as it likely did then. His take on the oeuvre performed in 1913 by Paris’ Ballets Russes–uniting the talents of Stravinsky, Nijinsky, and Diaghilev and loosely touching the theme of a maiden sacrifice; famous, too, for sparking a riot in a theater for its avant-garde music and choreography–comes from a time when Wood was pushing himself to create in a different way.

The dancers arrive, clad in white costumes of mid-length pants, gathering as though in a clearing. And immediately they are other. They are strange. They are animal.

To Stravinsky’s score, disquieting and drenched in dissonance, the dancers interact in duos and as a full group (often in a circle). Choreographic intensity builds palpably through a multitude of small gestures, through strange hand flicks and frozen moments; they point accusatory fingers, writhe in agony, or collapse in ways that make one think of marionettes–animated by what force? And through the dream-like washes and percussive explosions, the piece is held taut by physical prowess. One sequence has the dancers enact a chain of machine-like lunge-stepping that leaves one breathless. Wood leaned far into the otherworldly, and the dancers meet the challenge, until they coalesce into an animalistic, riotous, chaotic, Dionysiac writhing mass; and in a final pose, point up, then out to us.

The effect is absolutely riveting. Unexpected, every movement feels necessary. In that sense, this finale is the embodiment of catharsis.

“And I think that’s what carries the program as a whole,” says Bollinger. “We’re all not one thing. We’re all many things. We can connect to many things and be stirred by many things.”

The program has an incredible amount of range in that way. It wants you to react.

“It wasn’t a conscious decision,” to have Spring be super-charged, Bollinger says, but it is. “And I think people need to remember why you go to see a live performance.”

Get the FrontRow Newsletter

Author