It was Martin Heidegger who so well-defined place and space. A bridge is a place, he wrote; “as such a thing, it allows space into which earth and heaven, divinities and mortals are admitted. The space allowed by the bridge contains many places variously near or far from the bridge.” In other words, place is coordinate; space, a plane.

It was I who was worshiping a mere four months ago, standing in the well-lit galleries of the Fort Worth Modern, marveling at Mark Bradford’s florid yet lush, collage-like paintings. It was the opening day of Mark Bradford: End Papers, a mid-career retrospective exhibition focusing on Bradford’s artistic foundations: Los Angeles (the space where he grew up); and his mother’s hair salon (the place where he grew up). It was I who didn’t know that, within a week, all art museums would be closed because of a global pandemic. I wouldn’t even have finished my review by the time it happened.

But now they’re all there: dreadlocks, Jheri curls, end papers, 43G Spring Honey, 45R Spiced Cognac, hair curlers snapping into place, Click! Click! Click!

The Modern reopened on July 1. Moving from room to room, you will explore the evolution of Bradford’s art—the expansion of his subject and symbolism, as he’s gradually grown confident in who and where he is.

Born in 1961, Bradford grew up in his mother’s Los Angeles hair salon. It’s there that he became an artist. “It was the center of it all for me,” Bradford says. “You could say it was my first studio.” It’s there, weaving-braiding and painting-dyeing hair, that he first learned to use materials-mediums and work-create artistically.

In the 1980s, before settling into a hairdressing career, young, gay, Black Bradford hit the road to escape the AIDS crisis then sweeping the United States. He went to Europe, wandering by famous artworks in museums across the continent and falling in love with painting. But when he returned to the U.S. to study at CalArts, he learned that painting was at best passé, at worst kaput. He’d have to think of something else.

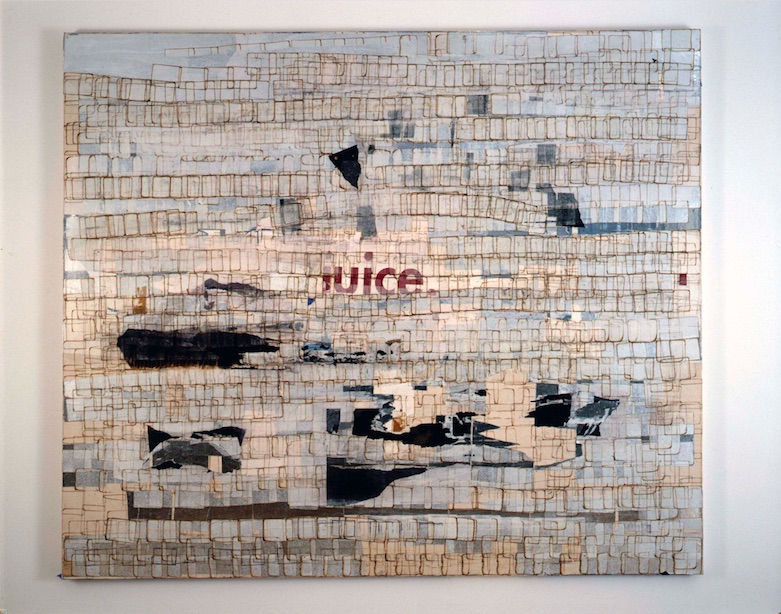

This was the point at which he began conceiving of his textural, pieced-together “paintings.” Pining to paint, but barred from it, Bradford decided to create painterly collages with end papers, which are used to protect hair from burning in the process of perming.

The resulting artworks recall both the gestures of abstract expressionism and the materialism of minimalism (a 1960s movement, the latter, in which artists impersonally mass-produced objects with materials significant to their personal histories).

“Enter and Exit the New Negro,” one of Bradford’s first exhibited artworks, exemplifies this synthesis. The “painting” has an impasto surface suggestive of abstract expressionist artist Jackson Pollock, and a gridded layout inspired minimalist artist Agnes Martin. But the medium itself—the end papers—references Bradford’s own foundation: the hair salon.

Of course, the personal is political. So that, as you walk through Mark Bradford: End Papers, you’ll witness the transformation of Bradford’s art from profoundly introspective to first timidly extrospective, then firmly critical. The saccharine canvas “It took me years to learn the right attitude” evokes the servile comportment that whites forced Blacks to adopt before them for many years. Across the gallery, “20 minutes from any bus stop” addresses income inequality, which disproportionately affects minorities, making them more dependent on public transportation systems in auto-centric U.S. cities.

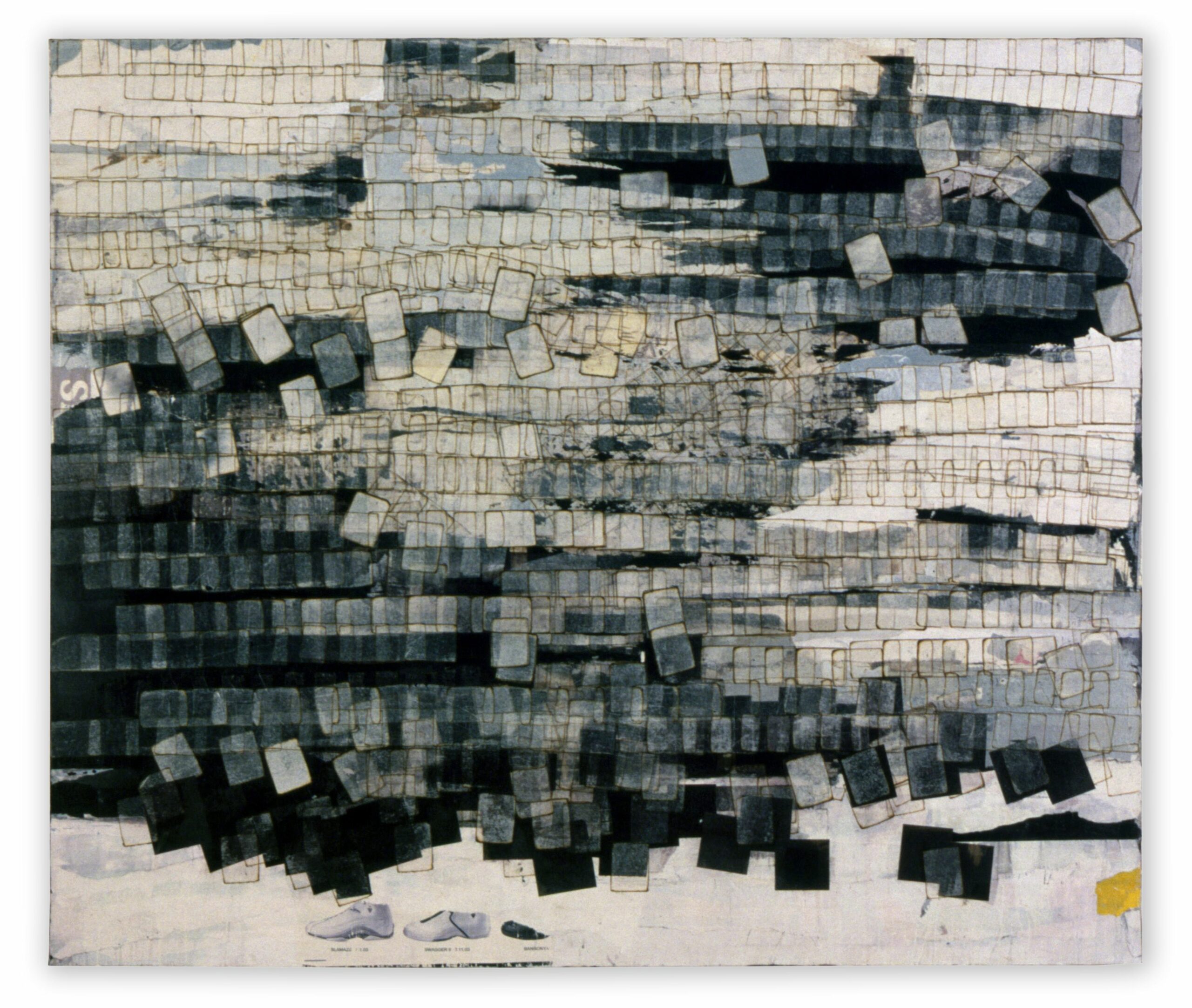

Continue walking and you’ll see Bradford expanding his subject from personal history rooted in place to community history enacted in space. Beyond end papers, he begins to incorporate merchant posters—homemade advertisements posted on walls or telephone poles, there one week, gone the next—into his collages. It’s the transience that attracted Bradford.

The overwhelming, sprawling, map-like work “Los Moscos,” in which he built a thick collage that he then sanded away to reveal fragments of photographs, advertisements, and merchant poster, probes this ephemeral nature of history. “The Some of It’s Parts,” a similar combination of collage and décollage, implies The rest of it’s whole. The fragmented parts of photos and ads, peeking at us from behind end papers, ask, What forgotten wholes lie beneath a simple text or photo? That Bradford not only collages, but décollages—cuts and removes—suggests the complexity of telling stories. Recounting history is as much deletion as it is recollection.

Mark Bradford: End Papers culminates with “Kingdom Day,” a monumental 10-by-40-foot canvas that celebrates the abrasive size and space of Los Angeles. It’s the consummation of Bradford’s growing interest in his sprawling hometown. According to the Modern, the artwork “refers to the annual Los Angeles parade of the same name that honors the birth of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.,” on January 15. More specifically, the piece refers to the 1992 parade, for which a Korean grand marshal was appointed; merely a few months later, a Korean woman murdered Latasha Harlins, a Black girl, and white policemen brutally beat Rodney King, a Black man. When the woman received probation, and the policemen were acquitted, protests exploded across L.A.

If anything, “Kingdom Day” seems to strive to turn space into place, which we can only do with history, both personal and communal. We can only turn space into place by entering into dialogue, listening to stories, gathering them and weaving them together. When we understand that stories are told by recounting and omitting and forgetting and deleting—when we understand that history is a process of accretion and deletion—we understand that we can only turn space into place by collaging and décollaging.