This summer, The Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth hosts two exhibitions highlighting the development of the twentieth century art scene in the Golden State. David Park: A Retrospective, which opened last weekend, and the highly conceptual Disappearing–California c. 1970: Bas Jan Ader, Chris Burden, Jack Goldstein, which opened last month, weave together two modern art movements from different parts of California.

Guest curated by Phillip Kaiser of Los Angeles, Disappearing occupies 13,000 square feet of the museum’s entire first floor. It is thematically organized, exploring how the three artists stretched the limitation of disappearance through performance. The show gets its name from Burden’s 1971 work “Disappearing,” in which he vanished from December 22-24.

Only a few years before, Ader created the installation “Please don’t leave me,” the show’s earliest piece (1969). A messy, tangled cluster of light fixtures dangle in front of thin, capitalized letters demanding “PLEASE DON’T LEAVE ME.” Of course, you have to leave the piece to continue through the show. (You’re not left to languish for long: Burden’s “Survival Kit” has all the viewer needs to proceed: a joint, a fake $100 bill, a candle, an army knife, and other essentials.) Goldstein’s videos, which show him moving, sitting, and exploring, round out the three artists’ early works.

Ader, Burden and Goldstein did not just intersect theoretically; they all knew each other as members of the burgeoning visual arts scene of Los Angeles, which Kaiser and scholars pinpoint to a surge of investment in higher education by the state and wealthy individuals in the ‘70s. At the time, the California Institute of the Arts (CalArts) was established by Walt Disney, the result of a merger with Chouinard Art Institute, also in LA, where Goldstein received a Bachelor of Fine Arts before receiving his MFA from CalArts. The University of California at Irvine had established what would become a well-known graduate visual arts program, which Burden attended. Ader, a Dutch immigrant, attended Otis College of Art and Design and Claremont Graduate University, later going on to teach at Irvine.

“They were doing similar things,” Kaiser says, and they were familiar with one another.

“Burden was obsessed with Ader, who didn’t like Burden’s work. Goldstein was obsessed with Burden, who didn’t care about Goldstein,” says Kaiser, “but Goldstein and Ader were friends.”

Burden is perhaps best known for self-mutilation, and collecting relics memorializing the occasion. Some of those items are on display. For “Disappearing,” Burden wrote, “I disappeared for three days without prior notice to anyone. On these days my whereabouts were unknown.”

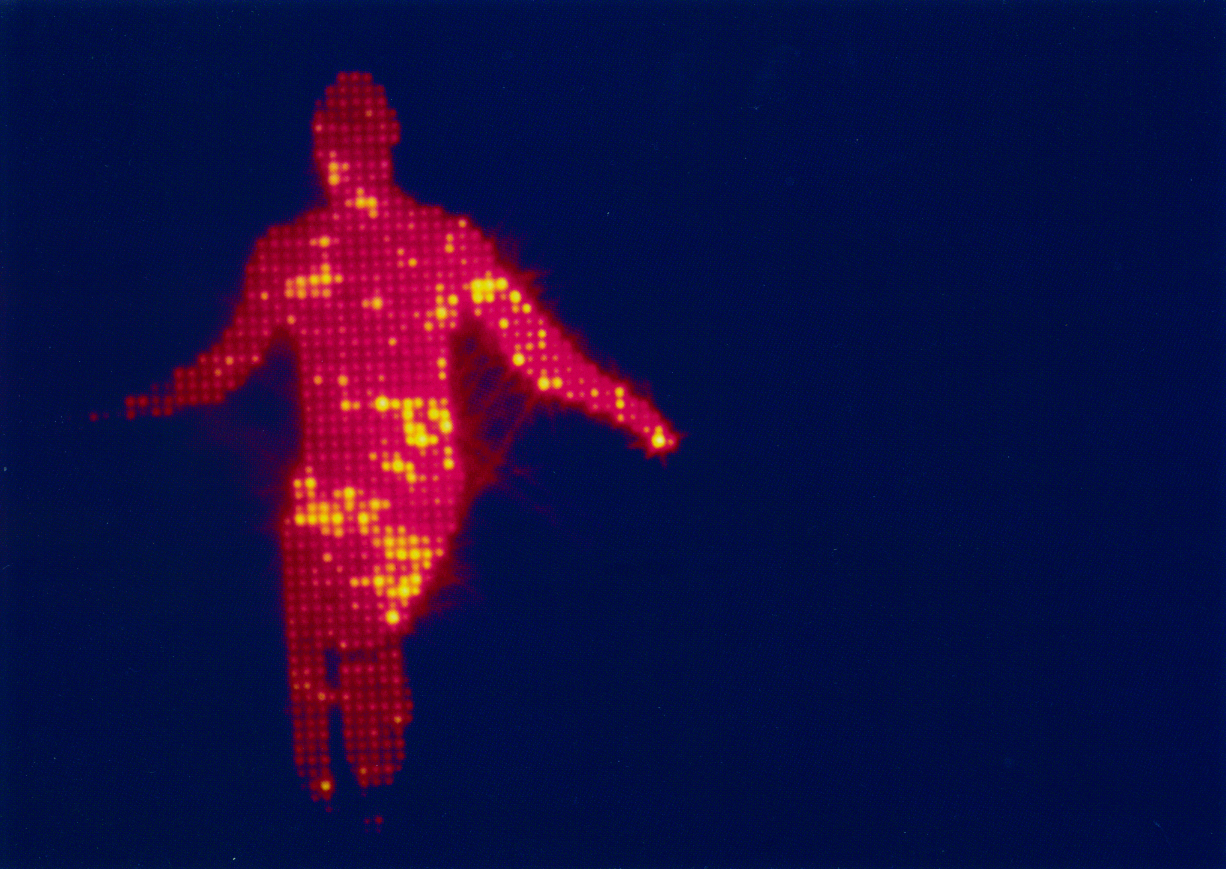

Goldstein made videos, shot photographs, and performed, inserting himself into the majority of his work–a common practice among his peers. For his graduate thesis, he performed “Burial Piece,” represented at The Modern by a poster advertising the event. The artist buried himself alive, but the audiences who gathered at CalArts on June 9, 1972 only saw a blinking light indicating that his heart was still beating.

Goldstein’s other works are playful and serious, including the vaguely biographical “Jack,” an 11-minute color video shot on 16 mm film, and “Suite of 9 Records with Sound Effects.” The albums of reconfigured sound bites, such as “A German Shepard” and “Two Wrestling Cats,” are a peculiar nod to Tinseltown.

“He was interested in the illusionism of film and wanted to turn it upside down,” Kaiser says. “These sounds were kind of a second wave pop.”

The albums share gallery space with three tilted boats and an accompanying sketch by Burden. The “Three Ghost Ships” were purchased by Burden for a project. The plan, Burden told Gary Wiseman, was to set the three boats off to sea fitted with GPS and solar panels. Funding fell through and only the boats were built.

However, the most prominent boat of this exhibition was lost at sea with Ader’s last work. In 1975, the artist and his wife Mary Sue Ader-Andersen recorded their journey to the East Coast. He would cross the Atlantic Ocean in that boat, Ocean Wave, and be greeted two months later by Ader-Anderson.

She recorded him sailing off. It was the last time she would see him. Rumors suggest he created a new life abroad, but that would defeat the purpose of disappearing–or radically redefine it.

Politics, a crux of West Coast conceptualism, were also at play. Some of Burden’s and Goldstein’s most dynamic works on display address the carnage of the Vietnam and Cold Wars. Burden’s 1979 work, “The Reason for the Neutron Bomb” is a collection of 50,000 coins with as many matchsticks displayed on top. Each coin represents a Soviet tank behind the Iron Curtain. The United States and NATO possessed only half that amount, “and that is the reason for the neutron bomb.”

With his guidance, Goldstein’s assistants created an extraordinary collection of acrylic canvases depicting bright white explosions taken from World War II photographs. The assistants were asked to airbrush away any sign Goldstein was involved, suggesting that not just history was disappearing, but the artist was, too.

Decades before that trio of artists was breaking ground in the LA art scene, painter David Park was part of a loose knit group of artists in the San Francisco Bay Area. David Park: A Retrospective is the first museum exhibition of his work in 30 years, spanning all of the museum’s second floor. Park practiced abstraction, abstract expressionism, and, later in his life, sketched large, colorful geometric objects. The contemporary of Richard Diebenkorn and Clyfford Still, whose work also appears in the show, was the founder of what became known as the Bay Area Figurative Group, a term the Modern’s associate curator Lee Hallman says, “was not a tradition but a name that just stuck.”

He was professionally trained at what is now the San Francisco Art Institute, but Janet Bishop, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art’s Thomas Weisel Family Curator of Painting and Sculpture, says he liked to think of himself as self-taught.

His best work came after he made a radical decision to discard nearly all of his early works in an East Bay dumping ground. Some surviving pieces are on display. Park’s career only flourished after ditching his biblical sketches and surrealist paintings. “Rehearsal,” 1954, shows a new awareness of his strengths, leading to the culmination to emotionally charged works like “Two Bathers” (1958).

Both exhibitions share a geographic connection and trace the development of two oft overlooked artistic movements that emerged in 20th century California. Disappearing is on view through August 11, and David Park is on view through September 22. General admission is $16. The museum offers half-price admission on Sundays and free admission on Fridays.