It’s the last day of the Oak Cliff Film Festival and Bridgette Mitchell is in the neighborhood 10 hours before the Dallas premiere of a movie she helped make called Never Goin’ Back. In a small shop tucked away from the venues, the stakes are low this time and there’s no set to dress. A cyanotype filmmaking session at Oil and Cotton is a chance for her to take part in building a short experimental film. Participants will use their hands, a few simple tools, and the most basic elements at the core of cinema: stock and light.

__

This year’s festival featured a premise that’s currently popular in theory and essentially fraught in practice as a frame. Its mission was to unearth lost stories of women, and stories told by women. Over the arc of the weekend festival audiences were required, just by surfing the lineup, to consider how lapses in the history of film and the world have affected our understanding of both. Keven Kerslake’s Bad Reputation opened to follow the life of Joan Jett, an emblem of rock and roll whose explosive presence and productive rage was more voluminous than audiences knew.

The guitarist and singer only spent a quarter of it onstage. Ills ate up the rest. Did you know, for example, that Jett recorded an album to help fund an investigation into the murder of Mia Zapata, frontperson for Seattle punk band the Gits? She was raped, beaten and strangled with the cord in her own sweatshirt as she walked home from a bar after last call in 1993.

“I could have been her, and she could have been me,” Jett says in the film, her eyes wet.

The inverse implication— that any of us could be Joan Jett— was just as potent. I started out of the theater ready to run five miles. Dallas performer Hannah Weir came toward me with her hands in the air. “Oh my god,” she said, her hair as dark as Jett’s, their pure energy at a kindred pitch. (Joan Jett just wanted to play, the film urged.) “Oh my GOD.”

Weir jumped up when Bad Reputation’s director appeared, asking him who’d approached whom about making the documentary. It was her idea, Kerslake said.

__

The team behind the Oak Cliff Film Festival and the Texas Theatre’s renovation is often credited with nurturing the Dallas film scene through funding and education. Saturday workshop hours at the 2018 festival, in its seventh year, were given to packed out sessions led by women on creative producing and fundraising, sponsored by the Austin Film Society and Seed&Spark, a record-setting crowdfunding and streaming service. Encouraging women to create and excel—and giving them each other as collaborators—is the best thing any festival can do within such an expressed frame. Fruits of endeavors like this are seen in the quality of the festival’s lineup, according to programmers.

“The good films, the ones we were after— the ones we’re chasing, which is something we have to do months and months in advance— 80 percent of what we wanted was made by women filmmakers,” Aviation Cinemas partner Jason Reimer says. “We weren’t really cognizant of the relationship to the topical aspect of that until we were well into the process of programming.”

Some of the selections this year referenced how the conversation about equity in film and the larger world, however crucial, leaves women who lead and participate in it feeling worn out. And there was an acknowledgement of how the misogyny of daily life can do the same.

A short by Sophy Romvari called Pumpkin Movie showed two women carving Halloween pumpkins together on Skype as they traded stories about men they didn’t know who’d asked to try on their underwear, or ordered female subordinates to scrub floors on their hands and knees. The clean living room of the friend who initiated the call, played by the director, glowed with a frame of string lights. I couldn’t stop thinking about the room and the choices that made it so effective as the character’s self-made haven. The conversation suffered on.

“Maybe next year we won’t have stories and we can carve our pumpkins in silence,” the woman told her friend, setting her knife down on the newspaper.

__

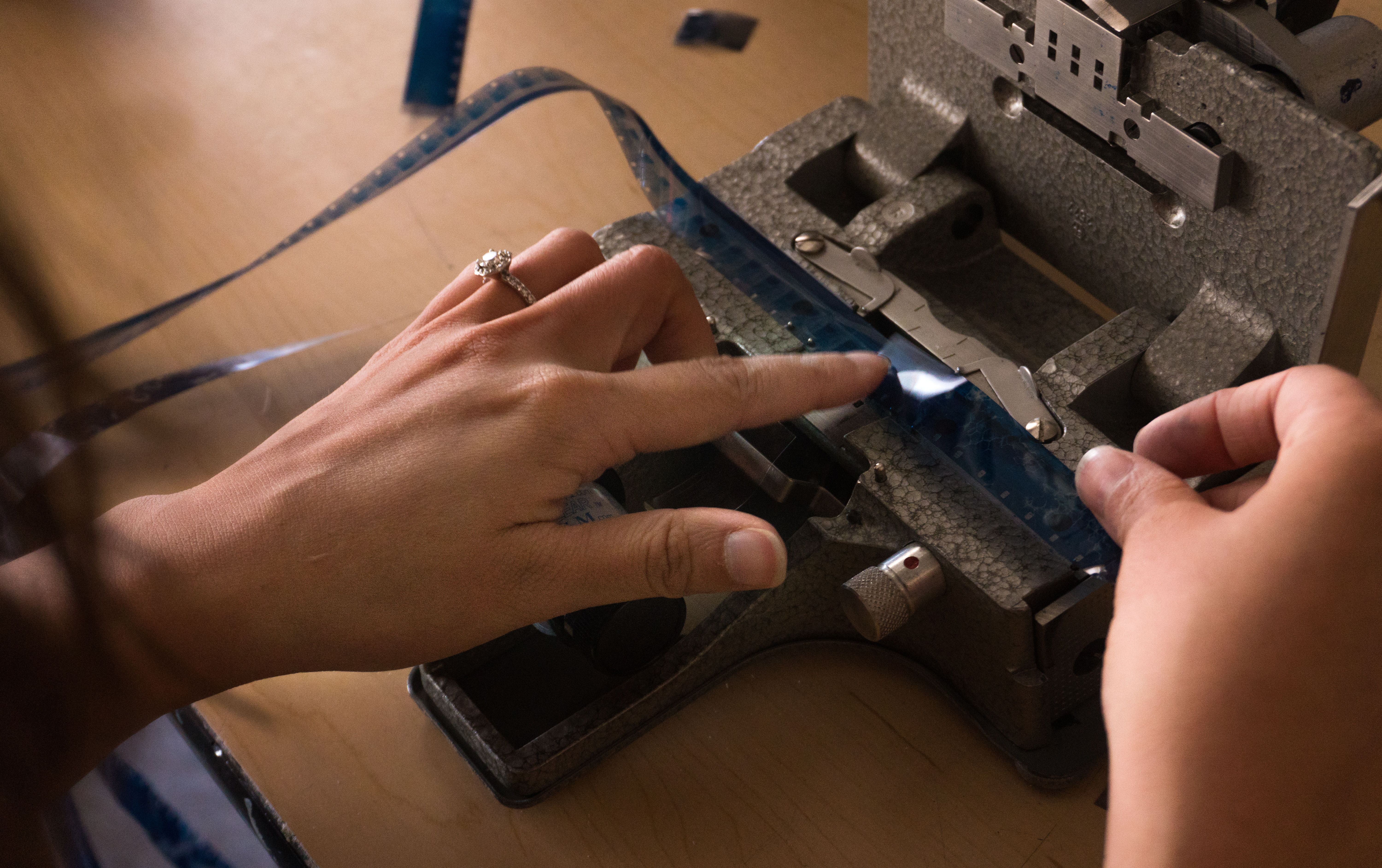

Back at Oil and Cotton, spools of 16mm film cover a cluster of tables. Mitchell is making not the set of this movie but the images themselves with confetti shapes, tulle, strips of synthetic leather, and feathers , along with Never Goin’ Back art department cohort Stephen McCormick and some strangers. Dallas artist and filmmaker Michael Morris demonstrates how the film, when exposed to natural light outside, will bear the impressions of these objects as arranged on the stock. He shows the class a film called Wake by his friend Eric Stewart, who used his father’s ashes in a deeply felt homage.

At the same time the class waits on their exposures, a short by Christina Ienna plays at the Kessler. Handmade Film is about a woman named Lindsay McIntyre who makes her own film emulsion—something done very rarely in the industry. The process takes three days.

Poetic double-bookings like this happened throughout the weekend. Pumpkin Movie screened at Bishop Arts Theatre with Marissa Maltz’s Ingrid, a documentary about a fed-up Dallas fashion designer who left the industry to build her own house in the woods. At the same time down the street, the documentary Half the Picture was addressing the absence of women’s perspectives in film.

Reimer attributed coincidences like that one to the bounty and tone of the films available to programmers.

“We definitely wanted to self-examine, but if you go back through our catalog of films, it’s always been diverse, getting more and more diverse,” Reimer says. “The community aspect of it is what we lean into the most.”

Saturday night Reimer was shooting iPhone video of skateboarders doing tricks outside Texas Theatre. They’d come to watch Crystal Moselle’s feature Skate Kitchen. The film, out in wide release in August, was conceived when Moselle ran into a group of teenagers on the train in New York. They carried boards, an affectionate skater girl gang with effusive chemistry and brightly colored clothes. She asked them to collaborate on a project and cast them in a film she wrote based on their lives. (They were even consultants during the writing process; they told her when the dialogue was wrong, when the slang belonged more to Moselle’s teenhood in the ‘90s than their own.)

One of the young skaters, Kabrina Adams, always holds a camera, shooting video of her friends while they pull flips and grinds, and sometimes bite the ground. Saturday at Texas Theatre she was there with the director and the rest of the cast, standing up front with that same camera, taking photos of the audience who cheered from the seats.

__

Behind the quest for equity in film is a desire to get at the truest picture, the clearest reflection. That manifests in different ways, in different projects. For Augustine Frizzell, the Dallas director behind the stoner comedy Never Goin’ Back, it took two tries. She scrapped the first version in 2014. Mitchell worked as property master on both. She oversaw the rolling of countless fake joints featured in the film, which was picked up for distribution by A24 and will see wide release in August like Skate Kitchen.

At the cyanotype workshop during a lunch break, Mitchell tells me she’s been writing a lot lately. The connections she’s made as a set dresser for Yen Tan’s 1985—another critically lauded film made by a mostly Dallas crew—are vast. McCormick, her art department friend, eyes the most compositionally elegant film strip drying on the rack, a feather’s fronds separated in perfect implied motion. “That’s Bridgette’s,” he laughs.

The group cuts their strips together and Morris projects the final product, a manic collage in blueprint-blue. Mitchell watches light dance on the projector. The tiny arrow-shaped jewels she placed on the film stock are sharp arpeggios. The sound crackles like fireworks while intention translates on the screen, as electric as Joan Jett’s coppery voice, the crash of skateboard wheels on pavement. Distilled. Undeniable.