This summer, The Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth is taken over by grinning flowers, Buddhist monks, imposing demons, sultry anime characters, and wriggling tentacles as it plays host to a retrospective for Japanese artist Takashi Murakami.

The Octopus Eats Its Own Leg arrived to Forth Worth directly from Vancouver, where it weathered the spring. At The Modern, the exhibition spans the entire second floor of the museum as well as several ground floor halls. It is set to run through September 16. Since its debut at The Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago last summer, the exhibition has been supplemented with additional pieces, both older and brand new. The bright octopus medallion overlooking the Modern’s main staircase is one of those newest, never-before-seen Murakami artworks.

Murakami is most familiar to the general public through his collaborations with the Louis Vuitton fashion brand and contributions to Kanye West’s album artwork. At 56, the founder of the art movement called Superflat has a Ph.D in traditional Japanese painting, is the president of the production and promotion company Kaikai Kiki, and remains one of the world’s best-selling contemporary artists.

Murakami’s enormous, elaborate silkscreen paintings can cost hundreds of thousands of dollars, and they are similarly expensive to produce. The artist compares himself to a movie director: he is a visionary who manages a veritable army of other artists, craftsmen, and support staff as they bring to life his unreasonably ambitious projects in a reasonable amount of time.

Accordingly, Murakami’s studio resembles nothing so much as a film factory: hundreds of crew workers scurry over the gleaming floors of blindingly lit pavilions, building frameworks and mixing colors. Others digitally manipulate silkscreen designs on sleek modern computers, while Murakami draws up endless concepts, approves alterations, micromanages color placement, and generally oversees each aspect of the work as it comes together in a stunning whole.

Takashi Murakami’s “art factory” is hardly a new concept. To the contrary, his Kaikai Kiki company operates on a similar model as the ateliers and workshops that have been the staple of artistic practice in most civilizations since antiquity. In addition to supporting young artisans, Kaikai Kiki promotes emerging artists and represents a number of them in Japan and internationally.

Although such an atelier system associates with the times gone by in the West, it remains commonplace in Japan, where many artist careers begin in large workshop studios that speed-produce popular graphic novels and animation. This inherently Japanese continuity between the “elite high” and “popular low” art, along with the interplay of western pop-culture and eastern artistic traditions, are the mainlines of Takashi Murakami’s work.

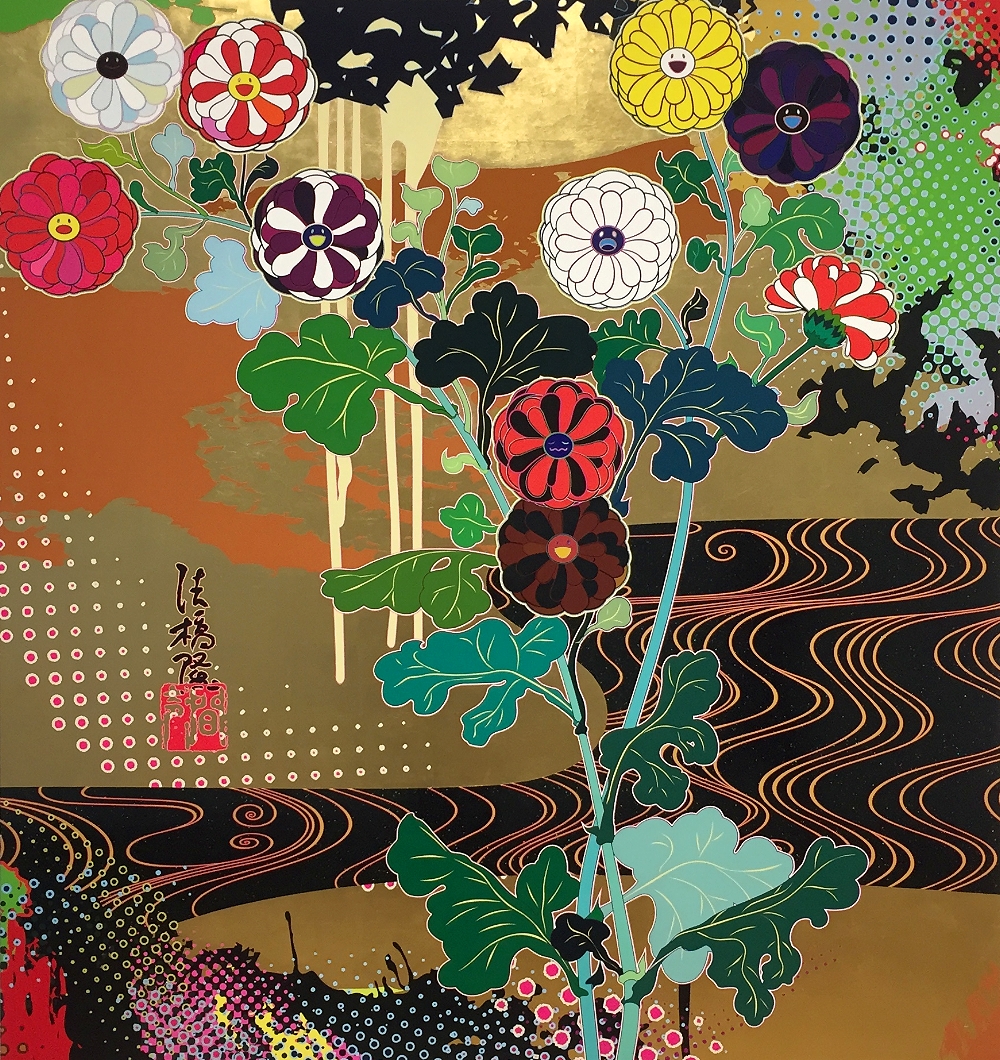

Murakami had discovered a particular passion for massive scale, intricate detail, eastern-style composition, and brilliant color while still a student, and as the more-or-less chronologically laid out exhibition highlights, his artistic growth has been exceptionally consistent throughout the years. Even Murakami’s earliest works on show, at first glance quite un-Murakami-like as they are delicately painted in muted, earthy tones on modestly easel-sized canvasses, contain the germs of future developments: superimposed overlays, minute attention to detail, wealth of patterns, and certain thematic elements to which the artist would return further along the line. For instance, the grim Nuclear Power Picture from 1988, completed two years after the Chernobyl disaster, in a way foreshadows the Isle of the Dead, 2014, a lurid painting of demented-looking Buddhist monks gathered in recognition of the devastation visited upon Japan in 2011 in the wake of a massive earthquake and a tsunami.

Subject matter notwithstanding, Murakami’s mature work is anything but somber as it overflows with bright colour and whimsical recurrent motifs. In the late 1990s, Murakami formulated the concept of Superflat: an artistic tradition inspired by the saturated consumer trends in the post-War Japanese culture. It may be said that the outpourings of simplified, garish, mutinously cute designs such as Hello Kitty have left both the culture and its audiences flattened, shallow, and empty at the core — or else this phenomenon may be reconsidered as natural evolution of eastern artistic traditions as transformed by the vagaries of modern life, population fluctuations, and the advance of technology. Murakami remarks that emptiness itself could be “the greatest art piece” of all, referencing the eastern approach to “emptiness” as a symbol of infinity, liberation, and the truth of all things. Appropriately, the artist’s purely non-representational paintings seem to draw the viewer into nothing else but looming, liquid black holes.

As Murakami’s career progressed and resources multiplied, his use of colour exponentially increased in complexity, until every swatch came to be made up of numerous overlapping shades in a mesmerising kaleidoscope of particles. That same level of detail applies to the inhabitants of Takashi Murakami’s artwork: happy-faced flowers, cartoonish monks, manga and anime elements, glossy mushrooms, creatures from eastern mythology, and of course the iconic Mr. DOB. The latter had started its life in the early 1990s as a decorative emblem reminiscent of popular cartoon characters like Doraemon and Mickey Mouse, but had evolved over the years into something of an “artist avatar”. Mr DOB frequently reappears in Murakami’s paintings and sculpture as either benign or menacing, lightly teasing or sardonically self-deprecating, and becomes something of a familiar companion for the visitor traversing the vast exhibition.

For a show that includes a “nudity and graphic content” warning, Octopus Eats Its Own Leg is remarkably child-friendly. The halls of the museum are turned into fanciful landscapes of polished sculptural confections and vibrant whirlpools of colour, splashed over every wall from floor to the ceiling. While aesthetes admire Murakami’s rich use of colour, and those analytically inclined contemplate the iterations of the artist’s recurrent characters, others yet could get hopelessly swallowed up by the staggering amount of unexpected little motifs that burst to life before the attentive viewer wherever their eye falls. Many of Murakami’s paintings inescapably conjure up the comparison to visual puzzle games like Where’s Waldo?, arresting attention for hours among a labyrinthine avalanche of detail. The cheerful brightness of the artwork seals the verdict: it is certain to entertain a child, and certainly a child in all of us.

As for the aforementioned content warning, a conscientious visitor might want to steer the youngest art lovers away from one particular exhibition hall. Here, two moderately explicit human-size sculptures of anime-inspired characters, set off by the blue background of a parody painting that extends the theme of bodily fluids, exemplify some of the Murakami’s commentary upon, among other things, the pervasive fetishism in the Japanese otaku culture. The humor and the polemic nature of these works, however, outstrip impropriety, and then again — as the works themselves rather pointedly remind the viewer — the children are likely to have seen worse, both in the sophisticated galleries of “high art” and among the ubiquitous sidewalk merchandise of the “low.”

Speaking of art and merchandise, Takashi Murakami has long been invested in the exploration and subversion of the frequently rigid western divide between the untouchable purity of fine art and the rampant commercialism of the modern consumer lifestyle. Murakami habitually appropriates pop-cultural elements, exports his work to fashionable brands, and re-appropriates them back subsequently. In a visual refrain of this practice, The Modern’s gift shop, filled with prints and souvenirs designed by Murakami, spills out in a colorful explosion of the artist’s unrepentant imagination across the museum’s cavernous atrium: for the summer, it is filled with dutifully flat, shamelessly bright, comically anthropomorphic flowers.