Beefhaus went out with a dejected whimper earlier this month with the collective’s final show In Loving Memory: Beefhaus RIP. A message on the Facebook event page encouraged visitors to wear “proper memorial attire” to grieve the final days of Beefhaus, during the crush of the Dallas Art Fair and surrounding openings. The Art Beef collective’s members didn’t take seriously those instructions to dress for a funeral.

Wearing black head to toe, I stepped inside the stark white walls of 833 Exposition Avenue to interview current members of Art Beef. There was an overall sense of reluctance to discuss why Beefhaus was closing, or what Art Beef’s objectives as a collective were going forward. It had been six months since an exhibition opened in the space.

I asked William Binnie, one of the original founding members, who curated the show. No one, he said. That makes sense, because the work was incohesive and felt inconsequential. Despondency and languor permeated from the gallery and its visitors.

“Five years is long enough. When we started we had no idea that we would make it to a six months or even a year,” Binnie says.

Art Beef was conceived August 6, 2012, by Luke Harnden, Adam Rico, William Binnie, Zachary Broadhurst, Crisman Liverman, and Nic Mathis. A year to the month later, the collective opened their own gallery— Beefhaus— in Exposition Park, where they hosted events and exhibitions organized by members and guest curators. The collective shifted goals and changed members over the years, but never classified itself as a nonprofit organization. Unlike other galleries that support mid-career artists alongside emerging artists, Beefhaus did not require the artists who showed there to give the gallery a percentage of what they earned from selling a piece. Instead, donations were encouraged, and the collective paid rent on those and other means.

Beefhaus was an invaluable staple in the community— a brick and mortar, independently owned, artist-run space, that facilitated shows for up-and-coming artists, bizzare new media works, and avant garde performances. Patrick Romeo, a previous member and curator at Beefhaus, says rent was $800 a month divided amongst five to 10 people. Other members confirmed rent did not increase.

“The rent wasn’t too bad. The real problem or cause of its demise was the shifting goals and values of the members,” Romeo says. “If something isn’t your first or second goal, you’re just not going to do it. That goes for any endeavor, and especially one that isn’t paying you. For a couple years it was my number one or number two goal, so I did it — with help from Luke Harnden and even non-members like Nick Gola and Freya Jardine helping here and there. Anybody who would push a broom or patch a wall, buy some beer or print some fliers.”

The space— and the artists behind it— endured a string of shutdowns by the fire marshal, which in 2016 focused hard on vetting DIY artspaces in Dallas. Artist Dean Terry led a performance art piece called The World’s Safest Art Show at Beefhaus to acknowledge and interpret the challenges artists faced during that time in planning and producing shows. Hazmat suits were employed.

Some believe the shutdowns depleted energy needed to sustain Beefhaus and those who ran it. The work in putting together shows as a collective was compounded by last-minute changes, weighing against freedom the artists enjoyed until then.

“I want to be clear: there is really no magic involved in curating shows. That’s a myth,” Romeo says. “There’s contacting artists who you want to show, picking work, installing it, cleaning, getting the lighting right, making a Facebook event, basic promotion and buying beer and ice for the night of. None of these steps are difficult [in themselves]. Without the normal capitalistic framework of the dire need to sell work, there wasn’t much to lose, except the investment of the rent paid.”

Life gets in the way, too, Romeo concedes.

“The remaining members were getting married, moving away, having kids, advancing their careers. There simply wasn’t time for them to focus on the space and actually do the labor required to make the shows happen every month, the way they should have been. I mean, we had shows for months while the fire marshal had essentially condemned us for not having our certificate of occupancy. There’s always ways to get around these blocks— better to ask forgiveness than permission. I mean… it’s not like [the owners] will rent [the space] out immediately. Your move, Dallas!” Romeo says.

“It took a lot of courage and dedication to have their own space, to have their own show and people to visit from other places,” says Sofia Bastidas, SMU Meadows gallery director and curator of past shows at Beefhaus. “Very admirable. One place that I could relate to, super DIY because of the lack of budget. Nice support from former members Patrick Romeo and Luke Harnden. One of the few artist-run spaces in Dallas that shows art and provides the community with something that is creating instead of taking culture. The city let this venue die. Beefhaus went through so much with the fire marshal and Dallas needs to do a better assessment of who needs grants. It’s an incredible loss for the city of Dallas,” she says.

Art Beef member Alison Starr says the collective will continue to manifest with a remote presence and pop-up shows.

What began as an outlet for a close-knit community of artists became a beloved resource for a larger group of art appreciators. I asked some Beefhaus regulars which shows they’ll remember most and why.

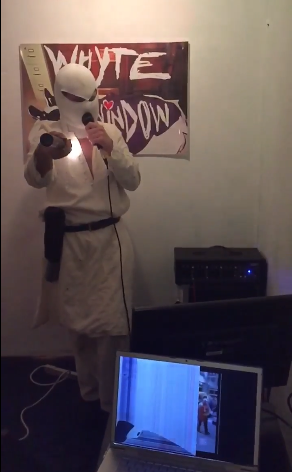

“My favorite experience there was the WHYTE WINDOW show with Thor Johnson and Joachim West. Had a tremendous time watching Thor in the vault singing karaoke for hours. He has a great voice. It was that night that I noticed that at least one kid must’ve grown up there, because inside the vault were dozens of height markings for children. Either kids grew to there or were held in the vault.” — Jordan Roth of Ro2

“There was a video William Sarradet made and it was shown on one of those night where they screened a lot of videos at once. For some reason I really loved that piece and I still remember that being a standout moment for me at Beefhaus.” — Dallas artist Michelle Rawlings

“My favorite work I saw at Beefhaus was Shelby David Meier’s Three Hypercubes Stacked, One Unfinished. I first saw it at the opening (which I was very late to) and the electronic function had been turned off (which I didn’t know at the time). I was alone in the room with the work, which at first I thought was composed of three static cubic frames, and the artist saw me and came over and turned it on and I was blown away buy this buzzing, dancing object that seemed to make the room dance with it. I remember thinking it was the making of that particular room, and that while I’d seen great work at Beefhaus, I’d never seen that space more engaged as a physical space.” — Dallas artist Erica Stephens

“Jessica Sinks’ show. Brad Tucker’s performance. Jessica’s work just hit the spot for me.The humor was a nerd-perfect blend of visual puns and intellectual doodles. Her thrifty linework was pitch perfect. Brad Tucker is playful genius. His multimedia performance comes across as a sweet deranged camp counselor sing along. He is much loved by many in the Texas art community.” — Dallas artist Brian Keith Jones

“Sean Miller and I collaborated with Cantoinette Studios to present a piece that we later showcased at The Oak Cliff Cultural Center. The work in progress show we did at Beefhaus was put together by Alison Starr as part of a collaboration with CentralTrak across the street. We worked with a dancer from Brown Girls Do Ballet. Alison approached Chesley [Antoinette] and Brown Girls Do Ballet. Chesley reached out to Sean and I.

Beefhaus was a wonderful use of space in the neighborhood. The people who worked there put so much time and effort into making Beefhaus a space for collaboration and challenging art. Beefhaus shows were about coming together as a creative community to see and talk about the work. Like so many instances in Dallas, there was a specific time and place that something like Beefhaus could exist and thrive. I feel lucky to have been able to perform in the space, and been able to see so many thought-provoking shows.” — Dallas artist and musician Lily Taylor

“I had my solo show Black Boxes and Dark Rooms there in 2016, and it was one of only a handful of places I could have seen working with in Dallas. Alternative spaces that are open to more experimental forms of art are really important to people with practices like mine that may not fit easily into other galleries’ models. It was an amazingly collaborative experience working with them, simultaneously an opportunity to do anything I wanted with no restrictions but also with quite a bit of help and support. Patrick Romeo spent several nights with me setting up my installation, and other members of the collective were also highly involved. In so many ways, they feel like the last bit of the wave of diy activity that had hit its stride in 2012. Maybe it’s for the best to move on from that moment in order to create a new one rather than holding on to something that was always going to be temporary.” — Dallas artist Michael Morris

Epistle (to Jenny Vogel) by Michael Morris, 2016. 16mm film loop, wood frame, tracing paper, micro controller, custom software, Youtube Livestream.