When Irby Pace found out his art was stolen from the Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts, he was deflated. The hijacked stereo cards had been a challenge to craft. Pace liked the fresh way they allowed viewers engage with his work. Plus, his subjects — vibrantly colored smoke clouds — looked super dope in 3D.

Now he’d have to start over.

He posted the news to his private social media accounts: “Some of my art was stolen from the Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts [fuming emoji, red emoji]” and added a doctored screenshot from the The Thomas Crown Affair.

As status updates go, it was simple and funny. Unless, of course, you’re the MMoFA. They weren’t thrilled with the shout-out. Due to the pieces’ scale and market price, they considered the whole thing a fender-bender of sorts — and they’d really rather nobody talk about it. To Curator of Art Jennifer Jankauskas, it didn’t merit a call to the cops.

“It’s not like a Monet got stolen,” she said in an interview. “The necessity of a police report doesn’t seem to make sense.”

Plus, Jankauskas told me, Pace’s work would not have been sellable after the exhibition, due to general wear and tear on the materials during the show’s run.

What followed was a charged exchange, one that would deal with free speech, the value of art, and the power politics between institutions and the artists they showcase. It also spurred other questions: Is successful interactive art less valuable due to material degradation, or more valuable due to its high level of engagement?

Pace’s gallerist, Ree Willaford of Galleri Urbane Marfa + Dallas, said that Pace wanted that human interaction, that DNA on the work. And besides: “Those could have been artist proofs,” she says from her Dallas showroom. “That’s not for us to decide. We all know Rauschenbergs don’t hold up well, but we’d all take one!”

“And it was supposed to be kept safe anyway, in any institution,” she says. “Whether it’s a gallery or museum.”

Irby was teaching a class at Troy University when he saw three missed calls. A week had passed since the theft and Pace had kind of found peace with the whole thing.

“How mad can you be when somebody loved [the work] so much they risked whatever they could have risked to steal it?” he asked.

Besides, now his stereo cards are in the canon of Art Stolen from Museums, which carries its own panache. And nobody can take that from him, right?

He checked the missed calls and rang the museum back. They wanted to settle up, name a price and close the loop with the artist. The press had started sniffing around and they needed this thing resolved. Once a monetary agreement was reached, they had a few more demands.

“They asked me not to make any social media postings, they asked me why I made any social media postings, and then they dictated that I need to go onto social media and explain that the thing has been resolved,” said Pace.

In a follow-up email, he was asked to stop giving information to reporters and to try and kill the story.

By the end of it, Pace felt censored, used and insulted.

“I was told that my artwork, because of the nature of it and the size of it, isn’t as important as the Edward Hoppers or other permanent collection work that it would be associated with. And what would validate a proper comment or investigation of theft.”

Questions about logistics enter here, too. Does additional oversight need to be put into a space where the public directly handles the art? And if so, who decides that? And if work is damaged, broken or lost to theft, how do its custodians talk about that with the public —or can they sweep it under the rug and silence the artist?

Surveying the museum landscape today, the public’s appetite for interactive artwork is only growing. As these institutions move away from Old Paintings on Walls, they’re being challenged to consider new rules and protocols. Meanwhile artists like Pace are left assuming more risk and murkier definitions of value. Should artists’ work leave a museum less valuable than when it entered it?

Irby Pace moved his family to Montgomery, Alabama in 2014 to accept a teaching position at nearby Troy. They left behind a Dallas arts community wherein Pace’s work had been quickly noticed. For his 2012 MFA show he made national headlines by ripping abandoned pictures of strangers off Apple store devices, blowing them up and calling it art. He presciently captured the cultural moment just before “selfie” happened. He also got tangled up with Apple in a dispute over privacy rights, freedom of speech and appropriation in a time of rapidly evolving technology.

The Dallas Observer awarded him “Best Art Heist” for the affair. That irony isn’t lost on Pace. “It’s kind of like a climatic response to that,” he said about the theft and laughed. “You can’t be THAT mad.”

But again, that was before the museum’s phone call.

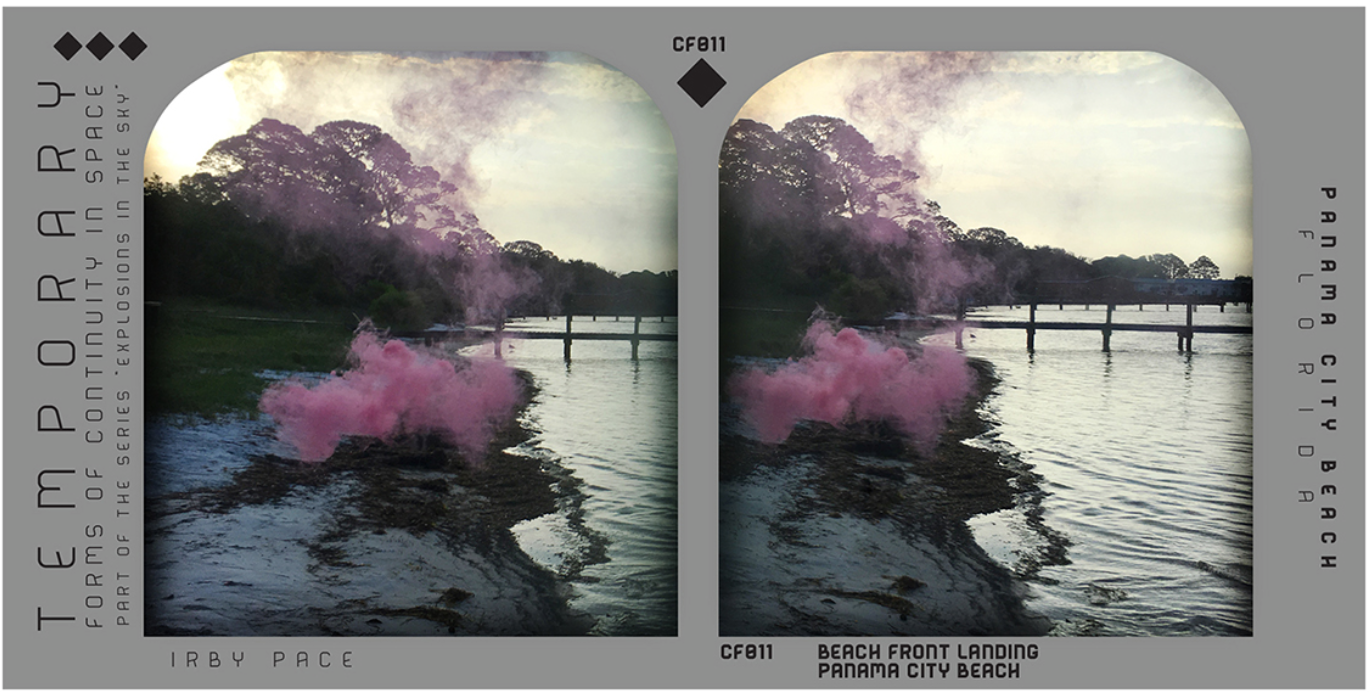

Pace’s stolen pieces were stereo card images. Shot on a special camera with two lenses, set at different angles, his work was laser cut and hand assembled over five months. It is the only set that exists. To use it, visitors place the cards into an antique viewer from the early 1900s and observe a three-dimensional illusion of his photography. It’s a fun gimmick that was popular more than one hundred years ago — another era when escapism was all the rage.

Their intimate size was part of what attracted Pace to the project. His big, blown up photographs were getting snatched up back at the gallery in Dallas and he’d have a few in this show as well. But he wanted to play with scale and guide viewers through his trippy environments in a more personal way. He chalked it up as a positive. The curators called the cards “minimal pieces” compared to the big guys on the wall and noted that they were replaceable.

Willaford again isn’t so sure this logic shakes out. She starts telling a story about her friend who ran a Houston gallery back in the ‘70s, who “sold (Donald) Judds when nobody wanted them.” For one fair in Germany, her friend carried the whole show in her purse. Cy Twombly had painted an entire series on popsicle sticks. “How much are those worth today?” asks Willaford. “That day they weren’t that valuable.”

While neither party is naming the settled payment price, both agree it’s enough to cover the material costs of creating a new set of slides. Pace may start a new series, but he won’t attempt to recreate the ones he’s lost.

“I’ll probably let that series be stolen and move onto the next one.” he says. Besides, he’s already considering other ways to bring his work to life, like large-scale holograms that dominate a showroom. And that seems like a great idea, one that’s really tough to steal.