Editor’s Note: The following is written by Dallas artists Darryl Ratcliff and Carol Zou. Ratcliff also writes a weekly arts column for DMagazine.com. They write here about their experience with the city via their monthlong Decolonize Dallas initiative, which aims to bring culture and art to areas of Dallas that lack access to it.

On April 4, we finished installing six banners at West Dallas Multipurpose Center as part of a month long Decolonize Dallas initiative, which was presented by the city of Dallas’ Office of Cultural Affairs. On April 5, we received a frantic email about the content of three of the banners. On April 6, before the artist or organizers could respond onsite, all of the banners were taken down.

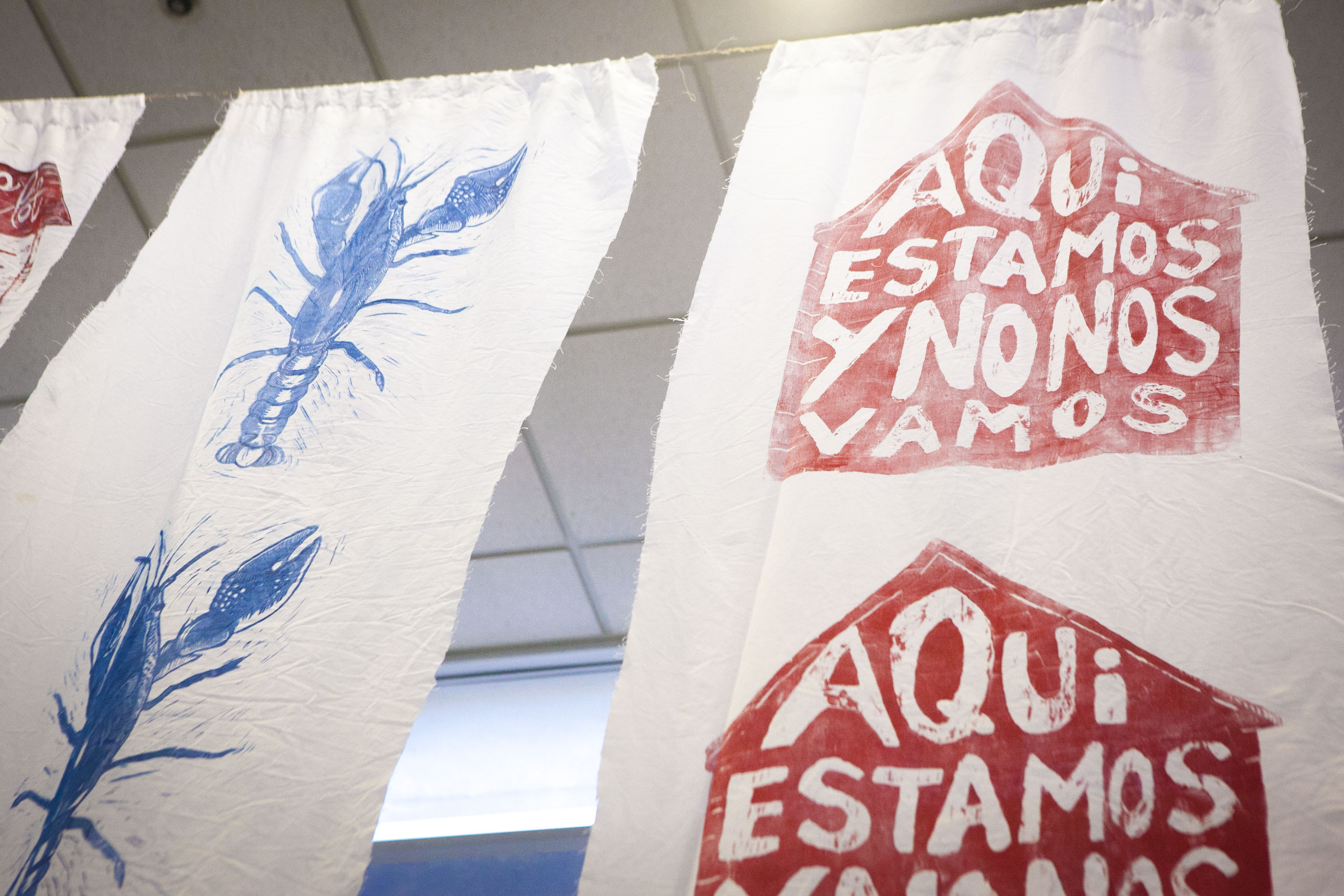

The banners in question were woodcut prints created over the course of four months by local artist Angela Faz, exploring migration and displacement in West Dallas. Three of the banners depicted house silhouettes with text written inside the silhouettes. Some of the text was specific to West Dallas, such as, “This house has a lot of value to me,” a direct quote from bcWorkshop interviews with West Dallas residents.

Others were more general, and pointed to language used in national debates over housing insecurity in Oakland, Portland, Brooklyn, and other neighborhoods. Faz drew upon her personal history as someone with local ties to the community, interviewing family members who had lived in the area and were at the risk of losing their homes. The same blood, sweat, and tears that went into her work were the same blood, sweat, and tears that went into building West Dallas.

We are unsure whom exactly made the decision to take down the banners at West Dallas Multipurpose Center. We do know that someone in a supervisory role at the West Dallas Multipurpose Center reached out to Jennifer Scripps, Director of the Office of Cultural Affairs, and Assistant City Manager Joey Zapata, demanding that they be taken down. According to our liaison at the center, they were concerned about references to the HMK tenant crisis in West Dallas and Councilwoman Monica Alonzo’s response as someone implicated in the crisis (to our knowledge, Councilwoman Alonzo has yet to see or comment on the prints).

We are unsure whom exactly made the decision to take down the banners at West Dallas Multipurpose Center. We do know that someone in a supervisory role at the West Dallas Multipurpose Center reached out to Jennifer Scripps, Director of the Office of Cultural Affairs, and Assistant City Manager Joey Zapata, demanding that they be taken down. According to our liaison at the center, they were concerned about references to the HMK tenant crisis in West Dallas and Councilwoman Monica Alonzo’s response as someone implicated in the crisis (to our knowledge, Councilwoman Alonzo has yet to see or comment on the prints).

According to West Dallas Multipurpose Center, they have a policy against showing political art, which was not communicated to us when we sent through the brief for Decolonize Dallas. Despite making no explicit reference to HMK or Councilwoman Alonzo, Faz’s work was deemed too political for exhibition. It was additionally communicated to us that they did not want the artwork to perturb the senior citizens who use the center. The great irony, of course, is that senior citizens are one of the demographic groups on fixed income that are rendered vulnerable by the lack of affordable housing in Dallas. (Ed. Note: We’ve reached out to the Office of Cultural Affairs for comment and will include it when they get back to us.)

Update — The Office of Cultural Affairs made the following statement.

The Office of Cultural Affairs is proud of the Decolonize Dallas initiative. Decolonize Dallas is the first arts commission funded in part by the City of Dallas for Dallas Arts Month. It came to our attention that the artwork provided by Angela Faz was removed. Upon further review, we are happy to say that Ms. Faz’s artwork is welcomed at the West Dallas Multipurpose Center. Many of our OCA staff have seen the Decolonize Dallas pieces and attended the panel discussion of participating artists at The Nasher Sculpture Center. We feel that the project has achieved its goal of spotlighting emerging artists and key issues across our city.

This was disheartening, but not surprising. Dallas is, after all, the city that placed Lauren Woods and Cynthia Mulcahy’s Negro Parks Project on indefinite hold because they dared to write historical texts about Dallas that referenced “white-only” parks.

The most poignant art about power, we’ve come to find, is the art that is suppressed immediately because of the fragility of the power structure that it touches up against and threatens to expose. Dallas thrives on having an opaque power structure that is inaccessible to many, and making space for community voices challenges that opacity. In a city heavily controlled by the interests of the private sector, public institutions and public spaces are often the only places where the average citizen can have a voice in shaping their communities. Our understanding of democracy and the commons dies the day that we designate the public sphere as a sphere controlled by the voices of the powerful at the expense of the vulnerable.

It is interesting to think about Woods and Mulcahy, and now Faz’s work, in the context of national debates about art, politics and censorship. Arts organizations across Dallas and the nation have been decrying the proposed elimination of the National Endowment for the Arts under the current administration, citing the elimination of artistic expression as one of the chilling first steps prefiguring a fascist government.

If the elimination of oppositional artistic viewpoints is fascism, then Dallas has been practicing de facto fascism for years. Censorship does not just happen through the elimination of public funding, but, as the city of Dallas expertly shows, through the refusal of exhibition opportunities, through non-inclusion in public panels, through non-inclusion in commissions and selection panels, through perfunctory community outreach efforts, through intentional bureaucratic red tape, and through sly phone calls with private interests.

Contrast this to the power dynamics present in everyone’s favorite dinner party conversation du jour, Dana Schutz’s much–maligned painting of Emmett Till at the 2017 Whitney Biennial. Supporters who equate criticism of the painting with a cry for censorship ignore the power dynamics at play with the particular painting, and with the cultural production of artists of color across the United States. To conflate censorship with a call for responsibility on the part of Schutz and the Whitney Biennial is to diminish the true censorship that happens daily to artists that are challenging the status quo.

If Schutz’s painting truly challenged the genocide of black Americans at the foundation of United States democracy, it would have been removed immediately. Instead, several protests, dozens of think pieces, and thousands of online comments later, a white artist’s facile representation of black trauma remains in a career-defining biennial, weather notwithstanding, while a local Latinx artist’s thoughtful representation of her community history is removed after one day in public view. The suffering of people of color, it seems, is only palatable when seen through the lens of whiteness.

No one said decolonization would be easy. This is the moment when we need to ask ourselves how committed we are as a city, as a community, to achieving racial equity. Are we only committed when it is comfortable and easy for us? Do we only recognize and reward artists and communities of color when they do not provoke the status quo? The problem with playing the docile minority is that as artists of color, we can try to be as generous and accommodating as possible, but the bare truth of our existence is inherently provocative. The truth of Faz’s experience is that of someone whose family is at risk of losing their home. As a community, do we suppress this uncomfortable truth about race, economics, and power in Dallas, or do we make space for it to be heard?

In doing this work, we are reminded of Skid Row-based artists Los Angeles Poverty Department, and their provocative question, “Do you want the cosmetic version or the real deal?”. All of our artists in Decolonize Dallas are the real deal, and we stand unflinchingly by their right to process their lived personal and community realities through art. In lieu of Faz’s work being on view, we encourage you to come together as a community, and share and support her work online.

Aquí estamos y no nos vamos.