The artist Esther Pearl Watson did not have a normal childhood. She grew up, as she puts it, in an orbit around Dallas, floating between houses in places like Wylie and Grand Prairie, moving whenever landlords finally kicked out her family, which never paid its rent.

At the center of this nomadic existence was her father. Gene Watson was a brilliant man who believed he had unlocked the secret engineering of flying saucers. He poured his life and soul into his project, drawing up complicated schematics, developing formulas, salvaging materials, and constructing prototypes of his spaceships on the family’s front lawn. Gene tried to attract attention to his ideas. He claims he had H. Ross Perot’s eye for a moment and that his designs were co-opted into secret government military programs. Nothing ever came of it, but Gene continued to spend all his time and what little money the family had on the obsession. Each consecutive landlord would eventually lose patience, and the family would have to pick up and move on.

It wasn’t until Esther Watson was in college that she began to make sense of her difficult, disruptive upbringing. She stumbled upon a copy of the magazine Raw Vision, which is dedicated to so-called “outsider artists,” the often eccentric, reclusive, or sometimes mentally handicapped talents whose work is distinctive for its apparent disinterest, dismissal, or distance from more mainstream contemporary art. Watson realized that her father wasn’t a failed NASA engineer. He was an artist, something of a contemporary Leonardo da Vinci, whose brilliant mind blurred the line between invention and creative expression.

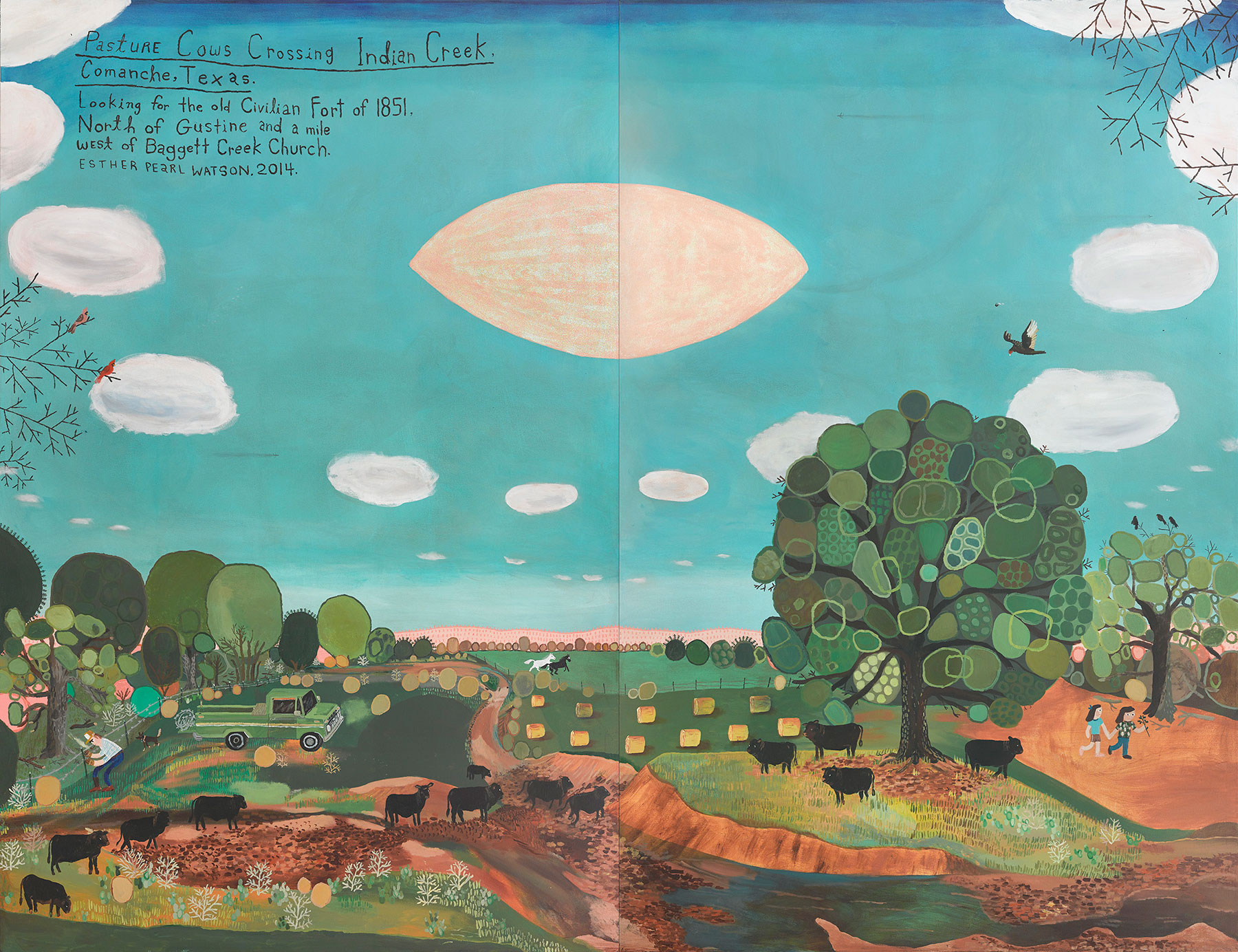

When Watson’s mural Pasture Cows Crossing Indian Creek, Comanche, Texas (2014) is installed this month in the atrium of the Amon Carter Museum of American Art, many visitors will likely identify it as a piece of outsider art. It is painted in the style of a child’s drawing, a cartoonish Texas landscape dominated by a silver, glittery flying saucer that hovers at the center of the composition. The saucer is surrounded by a ring of puffy white clouds. A creek runs left to right through the bottom of the two-panel painting, and there are about a dozen little black cows either making their way across it or taking shade under a tree. The trees are constructed like quilts, with blobs and shapes, some polka-dotted, others green and outlined in gold. Off to the left of the painting, a man with crude, rectangular blue jeans futzes with barbed wire, while on the far side of the landscape, two little girls skip through a meadow.

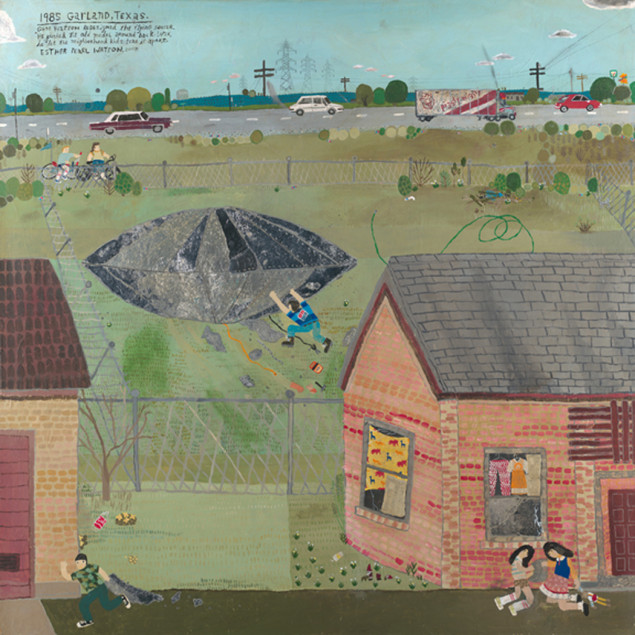

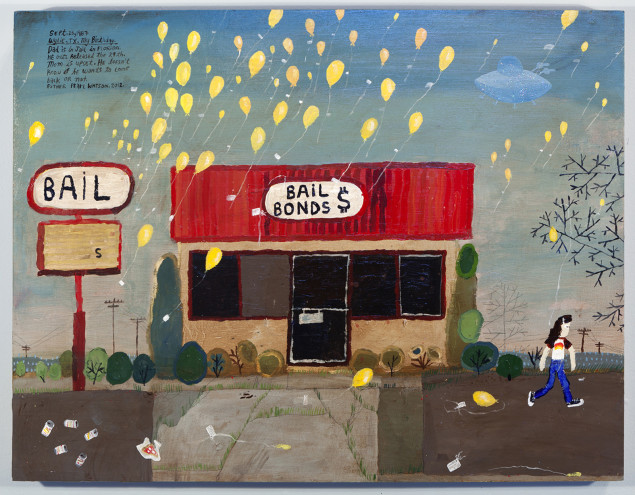

Like most of Watson’s paintings, it is connected to a specific memory from the artist’s childhood, indicated by childlike handwriting on the top left corner of the canvas. Her paintings at Waxahachie’s Webb Gallery, which will open an exhibit this month to correspond with the mural’s installation, show Watson returning to familiar settings and scenes—gas stations, fast-food restaurants, and suburban homes outside Dallas, often with her father building a flying saucer against horizons that are mucked up by power lines and vehicles that spew exhaust fumes. The paintings juxtapose innocence and banality, a lyrical imagination set adrift in an ugly, modern world. Even in Pasture Cows, which is more pastoral than many of her other works, Watson finishes the piece by using pencil to sketch airplanes dragging trails of exhaust across the blue sky, and scribbling out a thick cloud of fumes from the magical flying saucer.

So much about Watson’s work seems to suggest that it is the product of an outsider artist: its crude, seemingly untrained painting style; subjective iconography; the blur of realistic and fantastic subject matter; biographical references. But despite her eccentric father, Watson herself can’t quite claim outsider status. She received an MFA from the California Institute of the Arts in Los Angeles. She is a successful illustrator and the creator of the acclaimed comic Unlovable. In fact, even though Watson’s paintings look simple, childish, and unassuming, their peculiar but sophisticated adoption of an outsider aesthetic—cannily sidestepping a contemporary aversion to such simple, folksy imagery—raises challenging questions about how we define and understand her work as art.

What is outsider art, anyway? The term was first coined by British critic Roger Cardinal in 1972, but it was almost immediately recognized as problematic. Generally speaking, the outsiders are mentally ill recluses and eccentrics concerned with myopic obsessions, in dialogue with their impulses. What this work offered, aside from a colorful biographical backstory, was a sense that its creative expression conveyed something unfettered and “authentic”—untouched and untainted by any established ideas about art, art instruction, art historical theories, or art markets.

And yet the problems begin with the term itself. If there is something called “outsider art,” then there also must be “insider art.” And in recent years, outsider art’s increasing acceptance in the mainstream art world has brought it into the realm of the insiders. There’s the popular Outsider Art Fair in New York and Paris, museums have begun to collect and exhibit more of it, gallery shows by outsider artists make top-10 lists in major art publications, and, as a result of all of this, the market prices for outsider art have risen.

New York Times art critic Roberta Smith has argued that we should do away with the term “outsider art” altogether and just judge work according to its “level of artistry and power.” But there’s a problem with a simple dismissal of the outsider distinction. Outsider art is a kind of flotsam invented by modernism. As long as the various institutional and theoretical structures continue to exist around how we buy, sell, collect, exhibit, manage, and talk about art—thereby informing what we take to be art—anything left outside of those defining structures will become, well, outsider. Thus, Picasso is still considered more important than one of his inspirations, the untaught landscape painter Henri Rousseau; Gauguin is considered greater than the natives he imitated.

Because of the way Watson straddles these two worlds, her painting has been called “insider-outsider” or “faux-naïve,” pejorative terms that seem to imply a supposed lack of authenticity. And yet there is something very authentic about Watson’s work. What I love about it is its singular voice and the way its simplicity feels forced and held in tension by the subtle complexity of the composition. You notice a formal training, the sophistication of the layering and the astute use of color, scale, and form to lend the painting both physical and expressive depth. This is not a fake outsider painting. Although Watson is influenced by artists who might be labeled as outsiders, she also draws from outside of the art historical continuum—from illustration, comic books, and popular culture.

It is not surprising that Watson’s collectors include both Simpsons creator Matt Groening and contemporary artist Cindy Sherman. Thinking through the complex layering of personal and social narratives, authentic and adopted voices, there is something distinctively modern—and even postmodern—about paintings that otherwise bear aesthetic affinity to Grandma Moses. Watson’s paintings layer sweetness over a thinly veiled subtext of painful disorientation. They depict splintered narratives, real experience and the daydreams we invent to protect ourselves from reality. Like her father, Watson is trying to reconcile the conflict between interior and exterior worlds, bringing both together into a singular, unified romantic vision.

A version of this article appears in the May issue of D Magazine.